"Raj!" Thom Poplanich blurted.

Raj Whitehall's mouth quirked. "You sound more shocked this time," he said.

The way you look, I am more shocked, Thom thought, blinking and stretching a little. There was no physical need; his muscles didn't stiffen while Center held him in stasis. But the psychological satisfaction of movement was real enough, in its own way.

The silvered globe in which they stood didn't look different, and the reflection showed Thom himself unchanged—down to the shaving nick in his chin and the tear in his tweed trousers. A slight, olive-skinned young man in gentleman's hunting clothes, looking a little younger than his twenty-five years. He'd cut his chin before they set out to explore the vast tunnel-catacombs beneath the Governor's Palace in East Residence. The trousers had been torn by a ricocheting pistol-bullet, when the globe closed around them and Raj tried to shoot his way out. Everything was just as it had been when Raj and he first stumbled into the centrum of the being that called itself Sector Command and Control Unit AZ12-bl4-cOOO Mk. XIV.

That had been years ago, now.

Raj was the one who'd changed, living in the outer—the real—world. That had been obvious on the first visit, two years after their parting. It was much more noticeable this time. They were of an age, but someone meeting them together for the first time would have thought Raj a decade older.

"How long?" Thom said. He was half-afraid of the answer.

"Another year and a half."

Thom's surprise was visible. He's aged that much in so little time? he thought. His friend was a tall man, 190 centimeters, broad-shouldered and narrow-hipped, with a swordsman's thick wrists. There were a few silver hairs in the bowl-cut black curls now, and his gray eyes held no youth at all.

"Well, I've seen the titanosauroid, since," Raj went on.

"Governor Barholm did send you to the Southern Territories?"

Raj nodded; they'd discussed that on the first visit. After Raj's victories against the Colony in the east, he was the natural choice.

"A hard campaign, from the way you look."

"No," Raj said, moistening his lips. "A little nerve-racking sometimes, but I wouldn't call it hard, exactly."

observe, the computer said. The walls around them shivered. The perfect reflection dissolved in smoke, which scudded away—

—and returned as a ragged white pall spurting from the muzzles of volleying rifles. From behind a courtyard wall, Raj Whitehall and troopers wearing the red and orange neckscarves of the 5th Descott shot down an alleyway toward the docks of Port Murchison. Each pair of hands worked rhythmically on the lever, ting, and the spent brass shot backward, click, as they thumbed a new round into the breech and brought the lever back up, crack as they fired.

There were already windrows of bodies on the pavement: Squadron warriors killed before they knew they were at risk. Survivors crouched behind the corpses of their fellows and fired back desperately. Their clumsy flintlocks were slow to load, inaccurate even at this range; they had to expose themselves to reload, fumbling with powder horns and ramrods, falling back dead more often than not as the Descotter marksmen fired. A few threw the firearms aside with screams of frustrated rage, charging with their long single-edged swords whirling. By some freak one got as far as the wall, and a bayonet punched through his belly. The man fell backward off the steel, his mouth and eyes perfect O's of surprise.

A ball ricocheted from one of the pillars and grazed Raj's buttock before slapping into the small of the back of the officer beside him in the firing line. The stricken man dropped his revolver and pawed blindly at his wound, legs giving their final twitch. Raj shot carefully, standing in the regulation pistol-range position with one hand behind the back and letting the muzzle fall back before putting another round through the center of mass.

"Marcy!" the barbarians called in their Namerique dialect. Mercy! They threw down their weapons and began raising their hands. "Marcy, migo!" Mercy, friend!

Both men blinked as the vision faded—Raj to force memory away, Thom in surprise.

"You brought the Southern Territories back?" Thom said, slight awe in his voice. The Squadrones—the Squadron, under its Admiral—had ruled the Territories ever since they came roaring down out of the Base Area a century and a half ago and cut a swath across the Midworld Sea. The only previous Civil Government attempt to reconquer them had been a spectacular disaster.

Raj shrugged, then nodded: "I was in command of the Expeditionary Force, yes. But I couldn't have achieved anything without good troops—and the Spirit."

"Center isn't the Spirit of Man of the Stars, Raj. It's a Central Command and Control Unit from before the Collapse—the Fall, we call it now."

Neither of them needed another set of Center's holographic scenarios to remember what they had been shown. Earth—Bellevue, the computer always insisted—from the holy realm of Orbit, swinging like a blue-and-white shield against the stars. Points of thermonuclear fire expanding across cities . . . and the descent into savagery that followed. Which must have followed everywhere in the vast stellar realm the Federation once ruled, or men from the stars would have returned.

Raj shivered involuntarily. He had been terrified as a child, when the household priest told of the Fall. It was even more unnerving to see it played out before the mind's eye. Worse yet was the knowledge that Center had given him. The Fall was still happening. If Center's plan failed, it would go on until there was nothing left on Bellevue—anywhere in the human universe—but flint-knapping cannibal savages. Fifteen thousand years would pass before civilization rose again.

Thom went on: "Center's just a computer."

Raj nodded. Computers were holy, the agents of the Spirit, but Thom's stress on the word meant something different now. Different since he'd been locked in stasis down here, being shown everything Center knew. Nearly four years of continuous education.

"You know what you know, Thom," Raj said gently. "But I know what I know." He shook his head. "We slaughtered the whole Squadron," he went on. Literally. "Made them attack us, then shot the shit out of them."

"And how did Governor Barholm react?" Thom asked dryly. By rights, Thom Poplanich should have been Seated on the Chair; his grandfather had been. Barholm Clerett's uncle had been Commander of Residence Area Forces when the last Governor died, however, which had turned out to be much more important.

"Well, he was certainly pleased to get the Southern Territories back," Raj said, looking aside. That was hard to do inside the perfectly reflective sphere. "The expedition more than paid for itself, too—and that's not counting the tax revenues."

observe, Center said.

—and men in the black uniforms of the Gubernatorial Guard were marching Raj away, while the leveled rifles of more kept Suzette Whitehall and Raj's men stock-still—

—and Raj stood in a prisoner's breechclout and chains before a tribunal of three judges in ceremonial jumpsuits and bubble helmets—

—and he sat bound to an iron chair, as the glowing rods came closer and closer to his eyes—

Raj sighed. "That might have happened, yes. According to Center, and I don't doubt it myself. I was a little . . . apprehensive . . . about something like that. I'm not any more; the Army grapevine has been pretty conclusive. In fact, when the Levee is held this afternoon, I'm confident of getting another major command."

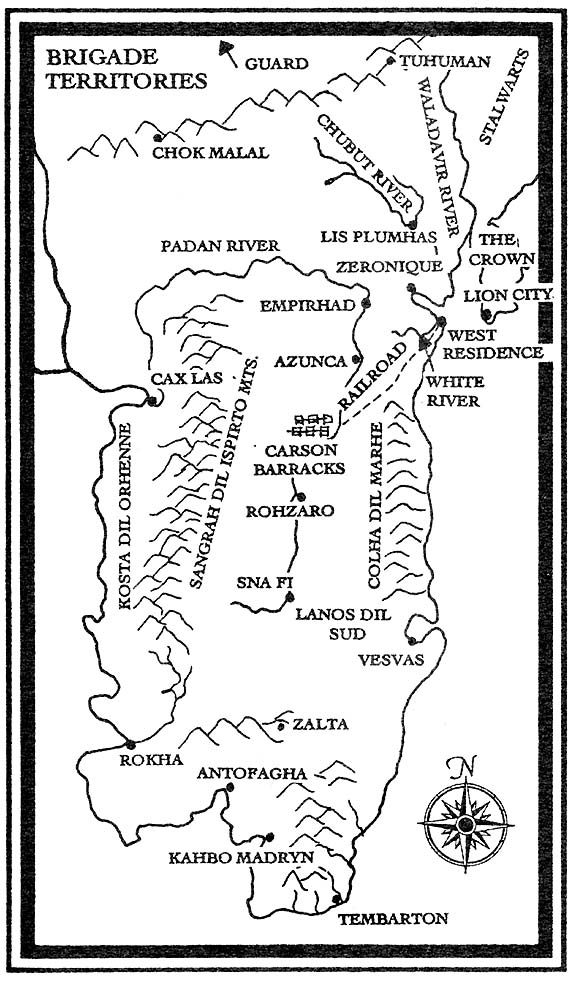

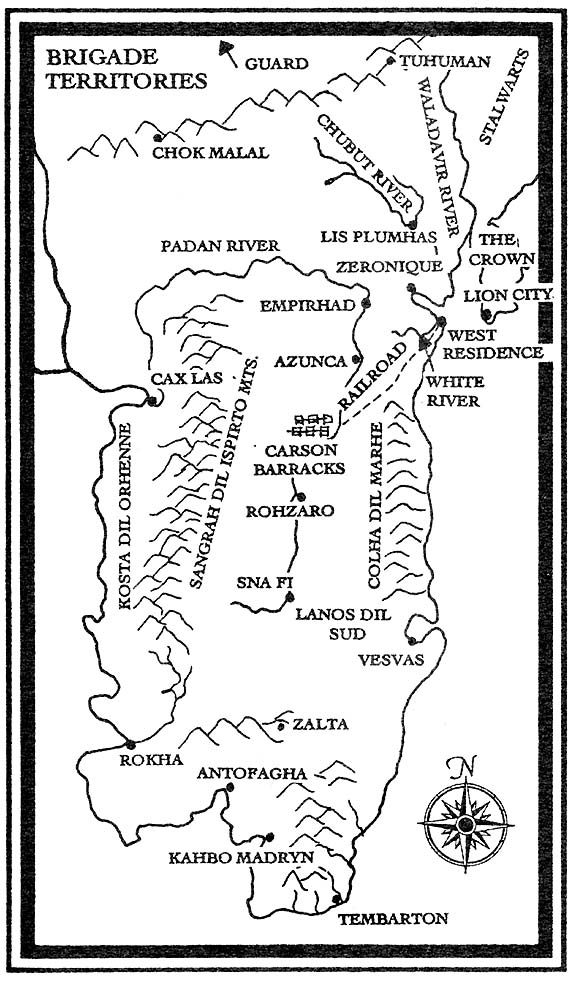

"The Western Territories?"

"How did you guess?"

"Even Barholm isn't crazy enough to try conquering the Colony. Yet."

"Yes." Raj nodded and ran a hand through his hair. "The problem is, he's probably too suspicious to give me enough men to actually do it."

Thom blinked again. Raj has changed, he thought. The young man he had known had been ambitious—dreaming of beating back a major raid from the Colony, say, out on the eastern frontier. This weathered young-old commander was casually confident of overrunning the second most powerful realm on the Middle Sea, given adequate backing. The Brigade had held the Western Territories for nearly six hundred years. They were almost civilized . . . for barbarians. Odd to think that they were descendants of Federation troops stranded in the Base Area after the Fall.

"Barholm," Raj went on with clinical detachment—sounding almost like Center, for a moment—"thinks that either I'll fail—"

observe, Center said.

Dead men gaped around a smashed cannon. The Starburst banner of the Civil Government of Holy Federation draped over some of the bodies, mercifully. Raj crawled forward, the stump of his left arm tattered and red, still dribbling blood despite the improvised tourniquet. His right just touched the grip of his revolver as the Brigade warrior reined in his riding dog and stood in the stirrups to jam the lance downward into his back. Again, and again . . .

"—or I'll succeed, and he can deal with me then."

observe, Center said.

Raj Whitehall stood by the punchbowl at a reception; Thom Poplanich recognized the Upper Promenade of the palace by the tall windows and the checkerboard pavement of the terrace beyond. Brilliant gaslight shone on couples swirling below the chandeliers in the formal patters of court dance; on bright uniforms and decorations, on the ladies' gowns and jewelry. He could almost smell the scents of perfume and pomade and sweat. Off to one side the orchestra played, the soft rhythm of the steel drums cutting through the mellow brass of trumpets and the rattle of marachaz. Silence spread like a ripple through the crowd as the Gubernatorial Guard troopers clanked into the room. Their black-and-silver uniforms and nickel-plated breastplates shone, but the rifles in their hands were very functional. The officer leading them bowed stiffly before Raj.

"General Whitehall—" he began, holding up a letter sealed with the purple-and-gold of a Governor's Warrant.

"Barholm doesn't deserve to have a man like you serving him," Thom burst out.

"Oh, I agree," Raj said. For a moment his rueful grin made him seem boyish again, all but the eyes.

"Then stay here," Thom urged. "Center could hold you in stasis, like me, until long after Barholm is dust. And while we wait, we can be learning everything. All the knowledge in the human universe. Center's been teaching me things . . . things you couldn't imagine."

"The problem is, Thom, I'm serving the Spirit of Man of the Stars. Whose Viceregent on Earth—"

bellevue, Center said.

"—Viceregent on Bellevue happens to be Barholm Clerett. Besides the fact that my wife and friends are waiting for me; and frankly, I wouldn't want my troops in anyone else's hands right now, either." He sighed. "Most of all . . . well, you always were a scholar, Thom. I'm a soldier; and the Spirit has called me to serve as a soldier. If I die, that goes with the profession. And all men die, in the end."

essentially correct, Center noted, its machine-voice more somber than usual. restoring interstellar civilization on bellevue and to humanity in general is an aim worth more than any single life. A pause, more than any million lives.

Raj nodded. "And besides . . . in a year, I may die. Or Barholm may die. Or the dog may learn how to sing."

They made the embrhazo of close friends, touching each cheek. Thom froze again; Raj swallowed and looked away. He had seen many men die. Too many to count, over the last few years, and he saw them again in his dreams far more often than he wished. This frozen un-death disturbed him in a way the windrows of corpses after a battle did not. No breath, no heartbeat, the chill of a corpse—yet Thom lived. Lived, and did not age.

He stepped out of the doorway that appeared silently in the mirrored sphere, into the tunnel with its carpet of bones—the bones of those Center had rejected over the years as it waited for the man who would be its sword in the world.

Then again, he thought, stasis isn't so bad, when you consider the alternatives.

"Bloody hell," Major Ehwardo Poplanich said, sotto voce. "How long is this going to take? If I'd wanted to sit on my butt and be bored, I would have stayed home on the estate." He ran a hand over his thinning brown hair.

He was part of the reason that Raj Whitehall and his dozen Companions had plenty of space to themselves on the padded sofa-bench that ran down the side of the anteroom. Nobody at Court wanted to stand too close to a close relation of the last Poplanich Governor. Quite a few wondered why Poplanich was with Raj; Thom Poplanich had disappeared in Raj's company years before, and Thom's brother Des had died when Raj put down a bungled coup attempt against Governor Barholm.

Another part of the reason the courtiers avoided them was doubt about exactly how Raj stood with the Chair, of course.

The rest of it was the other Companions, the dozen or so close followers Raj had collected in his first campaign on the eastern frontier or in the Southern Territories. Many of the courtiers had spent their adult lives in the Palace, waiting in corridors like this. The Companions seemed part of the scene at first, in dress or walking-out uniforms like many of the men not in Court robes or religious vestments. Until you came closer and saw the scars, and the eyes.

"We'll wait as long as His Supremacy wants us to, Ehwardo," Colonel Gerrin Staenbridge said, swinging one elegantly booted foot over his knee. He looked to be exactly what he was: a stylish, handsome professional soldier from a noble family of moderate wealth, a man of wit and learning, and a merciless killer. "Consider yourself lucky to have an estate in a county that's boring; back home in Descott County—"

"—bandits come down the chimney once a week on Starday," Ehwardo finished. "Isn't that right, M'lewis?"

"I wouldna know, ser," the rat-faced little man said virtuously.

The Companions were unarmed, despite their dress uniforms—the Life Guard troopers at the doors and intervals along the corridor were fully equipped—but Raj suspected that the captain of the 5th Descott's Scout Troop had something up his sleeve.

Probably a wire garrote, he thought. M'lewis had enlisted one step ahead of the noose, having made Bufford Parish—the most lawless part of not-very-lawful Descott County—too hot for comfort. Raj had found his talents useful enough to warrant promotion to commissioned rank, after nearly flogging the man himself at their first meeting—a matter of a farmer's pig lifted as the troops went past. The Scout Troop was full of M'lewis's friends, relatives and neighbors; it was also known to the rest of the 5th as the Forty Thieves, not without reason.

Captain Bartin Foley looked up from sharpening the inner curve of the hook that had replaced his left hand. His face had been boyishly pretty when Raj first saw him, four years before. Officially he'd been an aide to Gerrin Staenbridge, unofficially a boyfriend-in-residence. He'd had both hands, then, too.

"Why don't you?" he asked M'lewis. "Know about bandits coming down the chimney, that is."

Snaggled yellow teeth showed in a grin. "Ain't no sheep nor yet any cattle inna chimbley, ser," M'lewis answered in the rasping nasal accent of Descott. "An' ridin' dogs, mostly they're inna stable. No use comin' down t'chimbly then, is there?"

The other Companions chuckled, then rose in a body. The crowd surged away from them, and split as Suzette Whitehall swept through.

Messa Suzette Emmenalle Forstin Hogor Wenqui Whitehall, Raj thought. Lady of Hillchapel. My wife.

Even now that thought brought a slight lurch of incredulous happiness below his breastbone. She was a small woman, barely up to his shoulder, but the force of the personality behind the slanted hazel-green eyes was like a jump into cool water on a hot day. Seventeen generations of East Residence nobility gave her slim body a greyhound grace, the tilt of her fine-featured olive face an unconscious arrogance. Over her own short black hair she was wearing a long blond court wig covered in a net of platinum and diamonds. More jewels sparkled on her bodice, on her fingers, on the gold-chain belt. Leggings of embroidered torofib silk made from the cocoons of burrowing insects in far-off Azania flashed enticingly through a fashionable split skirt of Kelden lace.

Raj took her hand and raised it to his lips; they stood for a moment looking at each other.

A metal-shod staff thumped the floor, and the tall bronze panels of the Audience Hall swung open. The gorgeously robed figure of the Janitor—the Court Usher—bowed and held out his staff, topped by the star symbol of the Civil Government.

Suzette took Raj's arm. The Companions fell in behind him, unconsciously forming a column of twos. The functionary's voice boomed out with trained precision through the gold-and-niello speaking trumpet:

"General the Honorable Messer Raj Ammenda Halgern da Luis Whitehall, Whitehall of Hillchapel, Hereditary Supervisor of Smythe Parish, Descott County! His Lady, Suzette Emmenalle—"

Raj ignored the noise, ignored the brilliantly-decked crowds who waited on either side of the carpeted central aisle, the smells of polished metal, sweet incense and sweat. As always, he felt a trace of annoyance at the constriction of the formal-dress uniform, the skin-tight crimson pants and gilt codpiece, the floor-length indigo tails of the coat and high epaulets and plumed silvered helmet. . . .

The Audience Hall was two hundred meters long and fifty high, its arched ceiling a mosaic showing the wheeling galaxy with the Spirit of Man rising head and shoulders behind it. The huge dark eyes were full of stars themselves, staring down into your soul.

Along the walls were automatons, dressed in the tight uniforms worn by Terran Federation soldiers twelve hundred years before. They whirred and clanked to attention, powered by hidden compressed-air conduits, bringing their archaic and quite nonfunctional battle lasers to salute. The Guard troopers along the aisle brought their entirely functional rifles up in the same gesture. They ignored the automatons, but some of the crowd who hadn't been long at Court flinched from the awesome technology and started uneasily when the arclights popped into blue-white radiance above each pointed stained-glass window.

The far end of the audience chamber was a hemisphere plated with burnished gold, lit via mirrors from hidden arcs. It glowed with a blinding aura, strobing slightly. The Chair itself stood four meters in the air on a pillar of fretted silver, the focus of light and mirrors and every eye in the giant room. The man enchaired upon it sat with hieratic stiffness, light breaking in metallized splendor from his robes, the bejeweled Keyboard and Stylus in his hands. From somewhere out of sight a chorus of voices chanted a hymn, inhumanly high and sweet, castrati belling out the chorus and young girls on the descant:

"He intercedes for us—

Viceregent of the Spirit of Man of the Stars!

By Him are we boosted to the Orbit of Fulfillment—

Supreme! Most Mighty Sovereign, Lord!

In His hands is the power of Holy Federation Church—

Ruler without equal! Sole rightful Autocrat!

He wields the Sword of Law and the Flail of Justice—

Most excellent of Excellencies! Father of the State!

Download His words and execute the Program, ye People—

Endfile! Endfile! Ennd . . . fiiille."

On either side of the arch framing the Chair were golden trees ten times taller than a man, with leaves so faithfully wrought that their edges curled and quivered in the slight breeze. Wisps of white-colored incense drifted through them from the censers swinging in the hands of attendant priests in stark white jumpsuit vestments, their shaven heads glittering with circuit diagrams. The branches of the trees glittered also, as birds carved from tourmaline and amethyst and lapis lazuli piped and sang. Their song rose to a high trilling as the pillar that supported the Chair sank toward the white marble steps; at the rear of the enclosure two full-scale statues of gorgosauroids rose to their three-meter height and roared as the seat of the Governor of the Civil Government sank home with a slight sigh of hydraulics. The semicircle of high ministers came out from behind their desks—each had a ceremonial viewscreen of strictly graded size—and sank down in the full prostration, linking their hands behind their heads. So did everyone in the Hall, except for the armed guards.

The Companions had stopped a few meters back. Now Raj felt Suzette's hand leave his; she sank down with a courtier's elegance, making the gesture of reverence seem a dance. He walked three more steps to the edge of the carpet and went to one knee, bowing his head deeply and putting a hand to his breast—the privilege of his rank, as a general and as one of Barholm's chosen Guards. It might have done him some good to have made the three prostrations of a supplicant; on the other hand, that could be taken as an admission of guilt.

You never know, with Barholm, Raj thought. You never know. Center?

effect too uncertain to usefully calculate, the passionless inner voice said. After a pause: with barholm even chaos theory is becoming of limited predictive ability.

Raj blinked. There were times he thought Center was developing a sense of humor. That was obscurely disturbing in its own right. Dark take it, he'd never been much good at pleading anyway. Flickers of holographic projection crossed his vision; Barholm calling the curse of the Spirit down on his head, Barholm pinning a high decoration to Raj's chest—

Cloth-of-gold robes sewn with emeralds and sapphires swirled into Raj's view. The toes of equally lavish slippers showed from under them. A tense silence filled the Hall; Raj could feel the eyes on his back, hundreds of them. Like a pack of carnosauroids waiting for a cow to stumble, he thought. Then:

"Rise, Raj Whitehall!"

Barholm's voice was a precision instrument, deep and mellow. With the superb acoustics of the hall behind it, the words rolled out more clearly than the Janitor's had through the megaphone. Behind them a long rustling sigh marked the release of tension.

Raj came to his feet, bending slightly for the ceremonial embrace and touch of cheeks. He was several centimeters taller than the Governor, although they were both Descotters. Barholm had the brick build and dark heavy features common there, but Raj's father had married a noblewoman from the far northwest, Kelden County. Folk there were nearly as tall and fair as the Namerique-speaking barbarians of the Military Governments.

The two men turned, the tall soldier and the stocky autocrat. Barholm's hand rested on his general's shoulder, a mark of high favor. Behind them the bidden chorus sang a high wordless note.

"Nobles and clerics of the Civil Government—behold the man who We call Savior of the State! Behold the Sword of the Spirit of Man!" The orator's voice rolled out again. The chorus came crashing in on the heels of it:

"Praise him! Praise him! Praise him!"

Raj watched the throng come to their feet, putting one palm to their ears and raising the other hand to the sky—invoking the Spirit of Man of the Stars as they shouted, "Glory, glory!" and "You conquer, Barholm!"

Every one of them would have cheered his summary execution with equal enthusiasm—or greater.

Suzette's shining eyes met his.

not quite all, Center reminded him. Behind Suzette the Companions were grinning as they cheered, far less than all.

The cheering died as Barholm raised a hand. "On Starday next shall be held a great day of rejoicing in the Temple and throughout the city. For three days thereafter East Residence shall hold festival in honor of General Whitehall and the brave men he led to victory over the barbarians of the Squadron; wine barrels shall stand at every crossroads, and the government storehouses will dispense to the people. On the third day, the spoils and prisoners will be exhibited in the Canidrome, to be followed by races and games in honor of the Savior of the State."

This time the cheers were deafening; if there was one thing everyone in East Residence loved, it was a spectacle. The chorus was barely audible, and the sound rose to a new peak as Barholm embraced Raj once more.

"There'll be a staff meeting right after all this play-acting," he said into Raj's ear, his voice flat. "There's the campaign in the Western Territories to plan."

He turned, and everyone bowed low as he withdrew through the private entrance behind the Chair.

So passes the glory of this world, Raj thought. Death or victory, and if victory—

observe, Center said. Holographic vision shimmered before his eyes, invisible to any but himself:

It took a moment for Raj to recognize the naked man: it was himself, his face contorted and slick with the burnt fluid of his own eyeballs, after the irons had had their way with them. Thick leather straps held his wrists and ankles splayed out in an X.

The hooded executioners were just fastening each limb to the pull-chain of a yoke of oxen. The crowd beyond murmured, held back by a line of leveled bayonets.