All day I'd climbed through mountain country. Past Rebel Creek I'd climbed, and through Lost Cove, and up and down the slopes of Crouch and Hog Ham and Skeleton Ridge, and finally as the sun hunted the world's edge, I looked over a high saddleback and down on Flornoy College.

Flornoy's up in the hills, plain and poor, but it does good teaching. Country boys who mightn't get past common school else can come and work off the most part of their board and keep and learning. I saw a couple of brick buildings, a row of cottages, and barns for the college farm in the bottom below, with then a paved road to Hilberstown maybe eight, nine miles down valley. Climbing down was another sight farther, and longer work than you'd think, and when I got to the level it was past sundown and the night showed its stars to me.

Coming into the back of the college grounds, I saw a light somewhere this side of the buildings, and then I heard two voices quarreling at each other.

"You leave my lantern be," bade one voice, deep and hacked.

"I wasn't going to blow it out, Moon-Eye," the other voice laughed, but sharp and mean. "I just joggled up against it."

"Look out I don't joggle up against you, Rixon Pengraft."

"Maybe you're bigger than I am, but there's such a thing as the difference between a big man and a little one."

Then I was close and saw them, and they saw me. Scholars at Flornoy, I reckoned by the light of the old lantern one of them toted. He was tall, taller than I am, with broad, hunched shoulders, and in the lantern-shine his face looked good in a long, big-nosed way. The other fellow was plumpy-soft, and smoked a cigar that made an orangey coal in the night.

The cigar-smoking one turned toward where I came along with my silver-strung guitar in one hand and my possible-sack in the other.

"What you doing around here," he said to me. Didn't ask it, said it.

"I'm looking for Professor Deal," I replied him. "Any objections?"

He grinned his teeth white around the cigar. The lantern-shine flickered on them. "None I know of. Go on looking."

He turned and moved off in the night. The fellow with the lantern watched him go, then spoke to me.

"I'll take you to Professor Deal's. My name's Anderson Newlands. Folks call me Moon-Eye."

"Folks call me John," I said. "What does Moon-Eye mean?"

He smiled, tight, over the lantern glow. "It's hard for me to see in the night-time, John. I was in the Korean war, I got wounded and had a fever, and my eyes began to trouble me. They're getting better, but I need a lantern any night but when it's full moon."

We walked along. "Was that Rixon Pengraft fellow trying to give you a hard time?" I asked.

"Trying, maybe. He—well, he wants something I'm not really keeping away from him, he just thinks I am."

That's all Moon-Eye Newlands said about it, and I didn't inquire him what he meant. He went on: "I don't want any fuss with Rixon, but if he's bound to have one with me—" Again he stopped his talk. "Yonder's Professor Deal's house, the one with the porch. I'm due there some later tonight, after supper."

He headed off with his lantern, toward the brick building where the scholars slept. On the porch, Professor Deal came out and made me welcome. He's president of Flornoy, strong-built, middling tall, with white hair and a round hard chin like a water-washed rock.

"Haven't seen you since the State Fair," he boomed out, loud enough to talk to the seventy, eighty Flornoy scholars all at once. "Come in the house, John, Mrs. Deal's nearly ready with supper. I want you to meet Dr. McCoy."

I came inside and rested my guitar and possible-sack by the door. "Is he a medicine doctor or a teacher doctor?" I asked.

"She's a lady. Dr. Anda Lee McCoy. She observes how people think and how far they see."

"An eye-doctor?"

"Call her an inner-eye doctor, John. She studies what those Duke University people call ESP—extra-sensory perception."

I'd heard of that. A fellow named Rhine says folks can some way tell what other folks think to themselves. He tells it that everybody reads minds a little bit, and some folks read them a right much. Might be you've seen his cards, marked five ways—square, cross, circle, star, wavy lines. Take five of each of those cards and you've got a pack of twenty-five. Somebody shuffles them like for a game and looks at them, one after another. Then somebody else, who can't see the cards, in the next room maybe, tries to guess what's on them. Ordinary chance is for one right guess out of five. But, here and there, it gets called another sight oftener.

"Some old mountain folks would name that witch-stuff," I said to Professor Deal.

"Hypnotism was called witch-craft, until it was shown to be true science," he said back. "Or telling what dreams mean, until Dr. Freud overseas made it scientific. ESP might be a recognized science some day."

"You hold with it, do you, Professor?"

"I hold with anything that's proven," he said. "I'm not sure about ESP yet. Here's Mrs. Deal."

She's a comfortable, clever lady, as white-haired as he is. While I made my manners, Dr. Anda Lee McCoy came from the back of the house.

"Are you the ballad-singer?" she asked me.

I'd expected no doctor lady as young as Dr. Anda Lee McCoy, nor as pretty-looking. She was small and slim, but there was enough of her. She stood straight and wore good city clothes, and had lots of yellow hair and a round happy face and straight-looking blue eyes.

"Professor Deal bade me come see him," I said. "He couldn't get Mr. Bascom Lamar Lunsford to decide something or other about folk songs and tales."

"I'm glad you've come," she welcomed me.

Turned out Dr. McCoy knew Mr. Bascom Lamar Lunsford and thought well of him. Professor Deal had asked for him first, but Mr. Bascom was in Washington, making records of his songs for the Library of Congress. Some folks can't vote which they'd rather hear, Mr. Bascom's five-string banjo or my guitar; but he sure enough knows more old time songs than I do. A few more.

Mrs. Deal went to the kitchen to see was supper near about cooked. We others sat down in the front room. Dr. McCoy asked me to sing something, so I got my guitar and gave her "Shiver in the Pines."

"Pretty," she praised. "Do you know a song about killing a captain at a lonesome river ford?"

I thought. "Some of it, maybe. It's a Virginia song, I think. You relish that song, Doctor?"

"I wasn't thinking of my own taste. A student here—a man named Anderson Newlands—doesn't like it at all."

Mrs. Deal called us to supper, and while we ate, Dr. McCoy talked.

"I'll tell you why I asked for someone like you to help me, John," she began. "I've got a theory, or a hypothesis. About dreams."

"Not quite like Freud," put in Professor Deal, "though he'd be interested if he was alive and here."

"It's dreaming the future," said Dr. McCoy.

"Shoo," I said, "that's no theory, that's fact. Bible folks did it. I've done it myself. Once, during the war—"

But that was no tale to tell, what I dreamed in war time and how true it came out. So I stopped, while Dr. McCoy went on.

"There are records of prophecies coming true, even after the prophets died. And another set of records fit in, about images appearing like ghosts. Most of these are ancestors of somebody alive today. Kinship and special sympathy, you know. Sometimes these images, or ghosts, are called from the past by using diagrams and spells. You aren't laughing at me, John?"

"No, ma'am. Things like that aren't likely to be a laughing matter."

"Well, what if dreams of the future come true because somebody goes forward in time while he sleeps or drowses?" she asked us. "That ghost of Nostradamus, reported not long ago—what if Nostradamus himself was called into this present time, and then went back to his own century to set down a prophecy of what he'd seen?"

If she wanted an answer, I didn't have one for her. All I said was: "Do you want to call somebody from the past, ma'am? Or maybe go yourself into a time that's coming?"

She shook her yellow head. "Put it one way, John, I'm not psychic. Put it another way, the scientific way, I'm not adapted. But this young man Anderson Newlands is the best adapted I've ever found."

She told how some Flornoy students scored high at guessing the cards and their markings. I was right interested to hear that Rixon Pengraft called them well, though Dr. McCoy said his mind got on other things—I reckoned his mind got on her; pretty thing as she was, she could take a man's mind. But Anderson Newlands, Moon-Eye Newlands, guessed every card right off as she held the pack, time after time, with nary miss.

"And he dreams of the future, I know," she said. "If he can see the future, he might call to the past."

"By the diagrams and the words?" I inquired her. "How about the science explanation for that?"

It so happened she had one. She told it while we ate our custard pie.

First, that idea that time's the fourth dimension. You're six feet tall, twenty inches wide, twelve inches thick and thirty-five years old; and the thirty-five years of you reach from where you were born one place, across the land and maybe over the sea where you've traveled, and finally to right where you are now, from thousands of miles ago. Then the idea that just a dot here in this second of time we're living in can be a wire back and back and forever back, or a five-inch line is a five-inch bar reaching forever back thataway, or a circle is a tube, and so on. It did make some sense to me, and I asked Dr. McCoy what it added up to.

It added up to the diagram witch-folks draw, with circles and six-pointed stars and letters from an alphabet nobody on this earth can spell out. Well, that diagram might be a cross-section, here in our three dimensions, of something reaching backward or forward, a machine to travel you through time.

"You certain sure about this?" I inquired Dr. McCoy at last. And she smiled, then she frowned, and shook her yellow head again.

"I'm only guessing," she said, "as I might guess with the ESP cards. But I'd like to find out whether the right man could call his ancestor out of the past."

"I still don't figure out about those spoken spell words the witch-folks use," I said.

"A special sound can start a machine," said Professor Deal. "I've seen such things."

"Like the words of the old magic square?" asked Dr. McCoy. "The one they use in spells to call up the dead?"

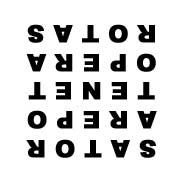

She got a pencil and scrap of paper, and wrote it out:

"I've been seeing that thing a many years," I said. "Witch-folks use it, and it's in witch-books like The Long Lost Friend."

"You'll notice," said Dr. McCoy, "that it reads the same, whether you start at the upper left and work down word by word, or at the lower right and read the words one by one upward; or if you read it straight down or straight up."

Professor Deal looked, too. "The first two words—SATOR and AREPO—are reversals of the last two. SATOR for ROTAS, and AREPO for OPERA."

"I've heard that before," I braved up to say. "The first two words being the last two turned around. But the third, fourth and fifth are all right—I've heard tell that TENET means faith and OPERA is works, and ROTAS something about wheels."

"But SATOR and AREPO are more than just reversed words," Professor Deal said. "I'm no profound Latinist, but I know that SATOR means a sower—a planter—or a beginner or creator."

"Creator," Dr. McCoy jumped on his last word. "That would fit into this if it's a real sentence."

"A sentence, and a palindrome," nodded Professor Deal. "Know what a palindrome is, John?"

I knew that, too, from somewhere. "A sentence that reads the same back and forward," I told him. "Like Napoleon saying, Able was I ere I saw Elba. Or the first words Mother Eve heard in the Garden of Eden, Madam, I'm Adam. Those are old grandma jokes to pleasure young children."

"If these words are a sentence, they're more than a palindrome," said Dr. McCoy. "They're a double palindrome, because they read the same from any place you start—backward, forward, up or down. Fourfold meaning would be fourfold power as a spell or formula."

"But what's the meaning?" I wanted to know again.

She began to write on a paper. "SATOR," she said out loud, "the creator. Whether that's the creator of some machine, or the Creator of all things . . . I suppose it's a machine-creator."

"I reckon the same," I agreed her, "because this doesn't sound to me the kind of way the Creator of all things does His works."

Mrs. Deal smiled and excused herself. We could talk and talk, she said, but she had sewing to do.

"AREPO," Professor Deal kind of hummed to himself. "I wish I had a Latin dictionary, though even then I might not find it. Maybe that's a corruption of repo or erepo—to crawl or climb—a vulgar form of the word—"

I said nothing. I didn't think Professor Deal would say anything vulgar in front of a lady. But all Dr. McCoy remarked him was: "AREPO—wouldn't that be a noun ablative? By means of?"

"Write it down like that," nodded Professor Deal. "By means of creeping, climbing, by means of great effort. And TENET is the verb to hold. He holds, the creator holds."

"OPERA is works, and ROTAS is wheels," Dr. McCoy tried to finish up, but this time Professor Deal shook his head.

"ROTAS probably is accusative plural, in apposition." He cleared his throat, long and loud. "Maybe I never will be sure, but let's read it something like this: The creator, by means of great effort, holds the wheels for his works."

I'd not said a word in all this scholar-talk, till then. TENET Might still be faith," I offered them. "Faith's needed to help the workings. Folks without faith might call the thing foolishness."

"That's sound psychology," said Professor Deal.

"And it fits in with the making of spells," Dr. McCoy added on. "Double meanings, you know. Maybe there are double meanings all along, or triple or fourfold meanings, and all of them true." She read from her paper. "The creator, by means of great effort, holds the wheels for his works."

"It might even refer to the orbits of planets," said Professor Deal.

"Where do I come in?" I asked. "Why was I bid here?"

"You can sing something for us," Dr. McCoy replied me, "and you can have faith."

A knocking at the door, and Professor Deal went to let the visitor in. Moon-Eye Newlands walked into the house, lifted his lantern chimney and blew out his light, He looked tall, the way he'd looked when first I met him in the outside dark, and he wore a hickory shirt and blue duckins pants. He smiled, friendly, and moon-eyed or not, he looked first of all at Dr. McCoy, clear and honest and glad to see her.

"You said you wanted me to help you, Doctor," he greeted her.

"Thank you, Mr. Newlands," she said, gentler and warmer than I'd heard her so far.

"You can call me Moon-Eye, like the rest," he told her.

He was a college scholar, and she was a doctor lady, but they were near about the same age. He'd been off to the Korean War, I remembered.

"Shall we go out on the porch?" she asked us. "Professor Deal said I could draw my diagram there. Bring your guitar, John."

We went out. Moon-Eye lighted his lantern again, and Dr. McCoy knelt down to draw with a piece of chalk.

First she made the word square, in big letters:

Around these she made a triangle, a good four feet from base to point. And another triangle across it, pointing the other way, so that the two made what learned folks call the Star of David. Around that, a big circle, with writing along the edge of it, and another big circle around that, to close in the writing. I put my back to a porch post. From where I sat I could read the word square all right, but of the writing around the circle I couldn't spell ary letter.

"Folks," said Moon-Eye, "I still can't say I like this."

Kneeling where she drew, Dr. McCoy looked up at him with her blue eyes. "You said you'd help if you could."

"But what if it's not right? My old folks, my grandsires—I don't know if they ought to be called up."

"Moon-Eye," said Professor Deal, "I'm just watching, observing. I hdven't yet been convinced of anything due to happen here tonight. But if it should happen—I know your ancestors must have been good country people, nobody to be ashamed of, dead or alive."

"I'm not ashamed of them," Moon-Eye told us all, with a sort of sudden clip in his voice. "I just don't think they were the sort to be stirred up without a good reason."

"Moon-Eye," said Dr. McCoy, talking the way any man who's a man would want a woman to talk to him, "science is the best of reasons in itself."

He didn't speak, didn't deny her, didn't nod his head or either shake it. He just looked at her blue eyes with his dark ones. She got up from where she'd knelt.

"John," she spoke to where I was sitting, "that song we mentioned. About the lonesome river ford. It may put things in the right tune and tempo."

Moon-Eye sat on the edge of the porch, his lantern beside him. The light made our shadows big and jumpy. I began to pick the tune the best I could recollect it, and sang:

Old Devlins was a-waiting

By the lonesome river ford,

When he spied the Mackey captain

With a pistol and a sword. . . .

I stopped, for Moon-Eye had tensed himself tight, "I'm not sure of how it goes from there," I said.

"I'm sure of where it goes," said someone in the dark, and up to the porch ambled Rixon Pengraft.

He was smoking that cigar, or maybe a fresh one, grinning around it. He wore a brown corduroy shirt with officers' straps to the shoulders, and brown corduroy pants tucked into shiny half-boots worth maybe twenty-five dollars, the pair of them. His hair was brown, too, and curly, and his eyes were sneaking all over Dr. Anda Lee McCoy.

"Nobody here knows what that song means," said Moon-Eye.

Rixon Pengraft sat down beside Dr. McCoy, on the step below Moon-Eye, and the way he did it, I harked back in my mind to something Moon-Eye had said: about something Rixon Pengraft wanted, and why he hated Moon-Eye over it.

"I've wondered wasn't the song about the Confederate War," said Rixon. "Maybe Mackey captain means Yankee captain."

"No, it doesn't," said Moon-Eye, and his teeth sounded on each other.

"I can sing it, anyway," said Rixon, twiddling his cigar in his teeth and winking at Dr. McCoy. "Go on picking."

"Go on," Dr. McCoy repeated, and Moon-Eye said nothing. I touched the silver strings, and Rixon Pengraft sang:

Old Devlins, Old Devlins,

I know you mighty well,

You're six foot three of Satan,

Two hundred pounds of hell. . . .

And he stopped. "Devils—Satan," he said. "Might be it's a song about the Devil. Think we ought to go on singing about him, with no proper respect?"

He went on:

Old Devlins was ready,

He feared not beast or man,

He shot the sword and pistol

From the Mackey captain's, hand. . . .

Moon-Eye looked once at the diagram, chalked out on the floor of the porch. He didn't seem to hear Rixon Pengraft's mocking voice with the next verse:

Old Devlins, Old Devlins,

Oh, won't you spare my life?

I've got three little children

And a kind and loving wife.

God bless them little children,

And I'm sorry for your wife,

But turn your back and close your eyes,

I'm going to take your—

"Leave off that singing!" yelled Moon-Eye Newlands, and he was on his feet in the yard so quick we hadn't seen him move. He took a long step toward where Rixon Pengraft sat beside Dr. McCoy, and Rixon got up quick, too, and dropped his cigar and moved away.

"You know the song," blared out Moon-Eye. "Maybe you know what man you're singing about!"

"Maybe I do know," said Rixon. "You want to bring him here to look at you?"

We were all up on our feet, We watched Moon-Eye standing over Rixon, and Moon-Eye just then looked about two feet taller than he had before. Maybe even more than that, to Rixon.

"If that's how you're going to be—" began Rixon.

"That's how I'm going to be," Moon-Eye told him, his voice right quiet again. "I'm honest to tell you, that's how I'm going to be."

"Then I won't stay here," said Rixon. "I'll leave, because you're making so much noise in front of a lady. But, Moon-Eye, I'm not scared of you. Nor yet the ghost of any ancestor you ever had, Devlins or anybody else."

Rixon smiled at Dr. McCoy and walked away. We heard him start to whistle in the dark. He meant it for banter, but I couldn't help but think about the boy whistling his way through the graveyard.

Then I happened to look back at the diagram on the porch. And it didn't seem right for a moment, it looked like something else. The two circles, with the string of writing between them, the six-point star, and in the very middle of everything the word square:

"Shoo," I said. "Look, folks, that word square's turned around."

"Naturally," said Professor Deal, plain glad to talk and think about something besides how Moon-Eye and Rixon had acted. "The first two words are reversals of the—"

"I don't mean that, Professor." I pointed. "Look. I take my Bible oath that Dr. McCoy wrote it out so that it read rightly from where I am now. But it's gone upside down."

"That's the truth," Moon-Eye agreed me.

"Yes," said Dr. McCoy. "Yes. You know what that means?"

"The square's turned around?" asked Professor Deal. "The whole thing's turned around. The whole diagram. Spun a whole hundred and eighty degrees—maybe several times—and stopped again. Why?" She put her hand on Moon-Eye's elbow, and the hand trembled. "The thing was beginning to work, to revolve, the machine was going to operate—"

"You're right." Moon-Eye, put his big hand over her little one, "Just when the singing stopped."

He moved away from her and picked up his lantern. He started away.

"Come back, Moon-Eye!" she called after him. "It can't work without you!"

"I've got something to see Rixon Pengraft about," he said.

"You can't hit him, you're bigger than he is!" I thought she was going to run and catch up with him.

"Stay here," I told her. "I'll go talk to him."

I walked quick to catch up with Moon-Eye. "Big things were near about to happen just now," I said.

"I realize that, Mr. John. But it won't go on, because I won't be there to help it." He lifted his lantern and stared at me. "I said my old folks weren't the sort you ruffle up for no reason."

"Was the song about your folks?"

"Sort of."

"You mean, Old Devlins?"

"That's not just exactly his name, but he was my great-grandsire on my mother's side. Rixon Pengraft caught onto that, and after what he said—"

"You heard that doctor lady say Rixon isn't as big as you are, Moon-Eye," I argued him. "You hit him and she won't like it."

He stalked on toward the brick building where the scholars had their rooms.

Bang!

The lantern went out with a smash of glass.

The two of us stopped still in the dark and stared. Up ahead, in the brick building, a head and shoulders made itself black in a lighted window, and a cigar-coal glowed.

"I said I didn't fear you, Moon-Eye!" laughed the voice of Rixon Pengraft. "Nor I don't fear Old Devlins, whatever kin he is to you!"

A black arm waved something. It was a rifle. Moon-Eye drew himself up tall in the dark.

"Help me, John," he said. "I can't see a hand before me.

"You going to fight him, Moon-Eye? When he has that gun?"

"Help me back to Professor Deal's." He put his hand on my shoulder and gripped down hard. "Get me into the light."

"What do you aim to do?"

"Something there wasn't a reason to do, till now." That was the last the either of us said. We walked back. Nobody was on the porch, but the door was open. We stepped across the chalk-drawn diagram and into the front room. Professor Deal and Dr. McCoy stood looking at us.

"You've come back," Dr. McCoy said to Moon-Eye, the gladdest you'd ever call for a lady to say. She made a step toward him and put out her hand.

"I heard a gun go off out there," she said,

"My lantern got shot to pieces," Moon-Eye told her, "I've come back to do what you bid me do. John, if you don't know the song—"

"I do know it, Moon-Eye," I said. "I stopped because I thought you didn't want it."

"I want it now," he rang out his voice. "If my great-grandsire can be called here tonight, call him. Sing it, John."

I still carried my guitar. I slanted it across me and picked the strings:

He killed the Mackey captain,

He went behind the hill,

Them Mackeys never caught him,

And I know they never will. . . .

Great-grandsire!" yelled out Moon-Eye, so that the walls shook with his cry. "I've taken a right much around here, because I thought it might be best thataway. But tonight Rixon Pengraft dared you, said he didn't fear you! Come and show him what it's like to be afraid!"

"Now, now—" began Professor Deal, then stopped it.

I sang on:

When there's no moon in heaven

And you hear the hound-dogs bark,

You can guess that it's Old Devlins

A-scrambling in the dark. . . .

Far off outside, a hound-dog barked in the moonless night.

And on the door sounded a thumpety-bang knock, the way you'd think the hand that knocked had knuckles of mountain rock.

I saw Dr. McCoy weave and sway on her little feet like a bush in a wind, and her blue eyes got the biggest they'd been yet. But Moon-Eye just smiled, hard and sure, as Professor Deal walked heavy to the door and opened it.

Next moment he sort of gobbled in his throat, and tried to shove the door closed again, but he wasn't quick enough. A wide hat with a long dark beard under it showed through the door, then big, hunched shoulders like Moon-Eye's. And, spite of the Professor's shoving, the door came open all the way, and in slid the long-bearded, big-shouldered man among us.

He stood without moving inside the door. He was six feet three, all right, and I reckoned he'd weigh at two hundred pounds. He wore a frocktail coat and knee boots of cowhide. His left arm cradled a rifle-gun near about as long as he was, and its barrel was eight-squared, the way you hardly see any more. His big broad right hand came up and took off the wide hat.

Then we could see his face, such a face as I'm not likely to forget. Big nose and bright glaring eyes, and that beard I tell you about, that fell down like a curtain from the high cheekbones and just under the nose. Wild, he looked, and proud, and deadly as his weight in blasting powder with the fuse already spitting. I reckon that old Stonewall Jackson might have had something of that favor, if ever he'd turned his back on the Lord God.

"I thought I was dreaming this," he said to us, deep as somebody talking from a well-bottom, "but I begin to figure the dream's come true."

His eyes came around to me, those terrible eyes, that shone like two drawn knives.

"You called me a certain name in your song," he said. "I've been made mad by that name, on the wrong mouth.

"Devlins?" I said.

"Devil Anse," he nodded. "The McCoy crowd named me that. My right name's Captain Anderson Hatfield, and I hear that somebody around here took a shoot at my great-grandboy." He studied Moon-Eye. "That's you, ain't it, son?"

"Now wait, whoever you are—" began Professor Deal.

"I'm Captain Anderson Hatfield," he named himself again, and lowered his rifle-gun. Its butt thumped the floor like a falling tree.

"That shooting," Professor Deal made out to yammer. "I didn't hear it."

"I heard it," said Devil Anse, "and likewise I heard the slight put on me by the shooter."

"I—I don't want any trouble—" the Professor still tried to argue.

"Nor you won't have none, if you hear me," said Devil Anse. "But keep quiet. And look out yonder."

We looked out the open door. Just at the porch stood the shadows of three men, wide-hatted, tall, leaning on their guns.

"Since I was obliged to come," said Devil Anse Hatfield, and his voice was as deep now as Moon-Eye's, "I reckoned not to come alone." He spoke into the night. "Jonce?"

"Yes, pa."

"You'll be running things here. You and Vic and Cotton Top keep your eyes cut this way. Nobody's to go from this house, for the law nor for nothing else."

"Yes, pa."

Devil Anse Hatfield turned back to face us. We looked at him, and thought about who he was.

All those years back, sixty, seventy, we thought to the Big Sandy that flows between West Virginia and Kentucky. And the fighting between the Hatfields and the McCoys, over what beginning nobody can rightly say today, but fighting that brought blood and death and sorrow to all that part of the world. And the efforts to make it cease, by every kind of arguer and officer, that couldn't keep the Hatfields and the McCoys apart from each other's throats. And here he was, Devil Anse Hatfield, from that time and place, picking me out with his eyes.

"You who sung the song," he nodded me. "Come along,"

I put down my guitar. "Proud to come with you, Captain," I said.

His hand on my shoulder gripped like Moon-Eye's, a bear-trap grip there. We walked out the door, and off the porch past the three waiting tall shadows, and on across the grounds in the night toward that brick sleeping building.

"You know where we're going?" I inquired him.

"Seems to me I do. This seems like the way. What's your name?"

"John, Captain."

"John, I left Moon-Eye back there because he called for me to come handle things. He felt it was my business, talking to that fellow. I can't lay tongue to his name right off."

"Rixon Pengraft?"

"Rixon Pengraft," he repeated me. "Yes, I dreamed that name. Here we are. Open that door for us."

I'd never been in that building. Nor either had Devil Anse Hatfield, except maybe in what dreams he'd had to bring him there. But, if he'd found his way from the long ago, he found the way to where he was headed. We walked along the hallway inside between doors, until he stopped me at one. "Knock," he bade me, and I put my fist to the wood.

A laugh inside, mean and shaky. "That you, Moon-Eye Newlands?" said Rixon Pengraft's voice. "You think you dare come in here? I've not locked myself in. Turn the knob, if you're man enough."

Devil Anse nudged my shoulder, and I opened the door and shoved it in, and we came across the threshold together.

Rixon sat on his bed, with a little old twenty-two rifle across his lap.

"Glad you had the nerve, Moon-Eye," he began to say, "because there's only room for one of us to sit next to Anda Lee McCoy—"

Then his mouth stayed open, with the words ceasing to come out.

"Rixon," said Devil Anse, "you know who I am?"

Rixon's eyes hung out of his head like two scuppernong grapes on a vine. They twitchy-climbed up Devil Anse, from his boots to his hat, and they got bigger and scareder all the time.

"I don't believe it," said Rixon Pengraft, almost too sick and weak for an ear to hear him.

"You'd better have the man to believe it. You sang about me. Named me Devil Anse in the song, and knew it was about me. Thought it would be right funny if I did come where you were."

At last that big hand quitted my shoulder, and moved to bring that long eight-square rifle to the ready.

"Don't!"

Rixon was on his knees, and his own little toy gun spilled on the floor between us. He was able to believe now.

"Listen," Rixon jibber-jabbered, "I didn't mean anything. It was just a joke on Moon-Eye."

"A mighty sorry joke," said Devil Anse. "I never yet laughed at a gun going off." His boot-toe shoved the twenty-two. "Not even a baby-boy gun like that."

"I—" Rixon tried to say, and he had to stop to get strength. "I'll—"

"You'll break up that there gun," Devil Anse decreed him.

"Break my gun?" Rixon was still on his knees, but his scared eyes managed to get an argue-look.

"Break it," said Devil Anse. "I'm a-waiting, Rixon. Just like that time I waited by a lonesome river ford."

And his words were as cold and slow as chunks of ice floating down a half-choked stream in winter.

Rixon put out his hand for the twenty-two. His eyes kept hold on Devil Anse. Rixon lifted one knee from the floor, and laid the twenty-two across it. He tugged at barrel and stock.

"Harder than that," said Devil Anse. "Let's see if you got any muscle to match your loud mouth."

Rixon tugged again, and then Devil Anse's rifle stirred. Rixon saw, and really made out to work at it. The little rifle broke at the balance. I heard the wood crack and splinter.

"All right now," said Devil Anse, still deep and cold and slow. "You're through with them jokes you think are so funny. Fling them chunks of gun out yonder."

He wagged his head at the open door, and Rixon flung the broken pieces into the hall.

"Stay on your knees," Devil Anse bade him. "You got praying to do. Pray the good Lord your thanks you got off so lucky. Because if there's another time you see me, I'll be the last thing you see this side of the hell I'm six foot three of."

To me he said: "Come on, John. We've done with this no-excuse for a man who's broke his own gun."

Back we went, and nary word between us. The other three Hatfields stood by Professor Deal's porch, quiet as painted shadows of three gun-carrying men. In at the door we walked, and there was Professor Deal, and over against the other side of the room stood Moon-Eye and Dr. McCoy.

"Rixon named somebody McCoy here," said Devil Anse. "Who owns up to the name?"

"I do," said she, gentle but steady.

"You hold away from her, Great-grandsire," spoke up Moon-Eye.

"Boy," said Devil Anse, "you telling me what to do and not do?"

"I'm telling you, Great-grandsire."

I looked at those two tall big-nosed men from two times in the same family's story, and, saving Devil Anse's beard, and maybe thirty-some-odd years, you couldn't have called for two folks who favored each other's looks more.

"Boy," said Devil Anse, "you trying to scare me?"

"No, Great-grandsire. I'm not trying to scare you."

Devil Anse smiled. His smile made his face look the terriblest he'd looked so far.

"Now, that's good. Because I never been scared in all my days on this earth."

"I'm just telling you, Great-grandsire," said Moon-Eye. "You hold away from her."

Dr. McCoy stood close to Moon-Eye, and all of a sudden Moon-Eye put his hickory-sleeved arm round her and drew her closer still.

Devil Anse put his eyes on them. That terrible smile crawled away out of his beard, like a deadly poison snake out of grass, and we saw it no more.

"Great-grandboy," he said, "it wasn't needful for you to get me told. I made a mistake once with a McCoy girl. Jonce—my son standing out yonder—loved and courted her. Roseanna was her name."

"Roseanna," said the voice of Jonce Hatfield outside.

"I never gave them leave to marry," said Devil Anse. "Wish I had now. It would have saved a sight of trouble and grief and killing. And nobody yet ever heared me say that."

His eyes relished Dr. McCoy, and it was amazing to see that they could be quiet eyes, kind eyes.

"Now, girl," he said, "even if you might be close kin to Old Ran McCoy—"

"I'm not sure of the relationship," she said. "if it's there, I'm not ashamed."

"Nor you needn't be." His beard went down and up as he nodded her. "I've fit the McCoy set for years, and not once found ary scared soul among them. Ain't no least drop of coward blood in their veins." He turned. "I'll be going."

"Going?" asked Professor Deal.

"Yes, sir. Goodnight to the all of you."

He went through the door, hat, beard and rifle, and closed it behind him, and off far again we could hear that hound-dog bark.

We were quiet as a dead hog there in the room. Finally:

"Well, God bless my soul!" said Professor Deal.

"It happened," I said.

"But it won't be believed, John," he went on. "No sane person will ever believe who wasn't here."

I turned to say something to Moon-Eye and Dr. McCoy. But they were looking at each other, and Moon-Eye's both arms were around that doctor lady. And if I had said whatever I had in mind to say, they'd not have been hearing me.

Mrs. Deal said something from that room where she'd gone to do her sewing, and Professor Deal walked off to join her. I felt I might be one too many, too, just then. I picked up my silver-strung guitar and went outside after Devil Anse Hatfield.

He wasn't there, nor yet those who'd come with him. But on the porch was the diagram in chalk, and I had enough light to see that the word-square read right side up again, the way it had been first set down by Dr. Anda Lee McCoy.

McCoy. Mackey. Devlins. Devil Anse. Names change in the old songs, but the power is still there. Naturally, the way my habit is, I began to pick at my silver strings, another song I'd heared from time to time as I'd wandered the hills and hollows:

Up on the top of the mountain,

Away from the sins of this world,

Anse Hatfield's son, he laid down his gun

And dreamed about Ran McCoy's girl. . . .