As I have been bidden, I will tell of how the sorcerer Merlin Ambrosius came to the shores of Ireland, and what he did there. Ambrosius was sometimes called No Man's Son, but because of these deeds I am to tell you now, he also had a third name, and that was the Thief of Stones.

He came alone to the shores of the blessed isle. Some say he flew there, having power over the wind as he had over the earth, but this is not so. Merlin Ambrosius was child of the west lands and its ragged coasts. He traveled in a boat of reeds and skins, with a brown sail to catch the winds and a stout oar to steer him through the rough grey waves of that sea. Autumn spread rust and gold over Briton's lands when he left there, and he came to the green shores on a day of chill rain and mist. It is often so in Ireland, and that is why her waters are deep and her fields more green than any others on the earth.

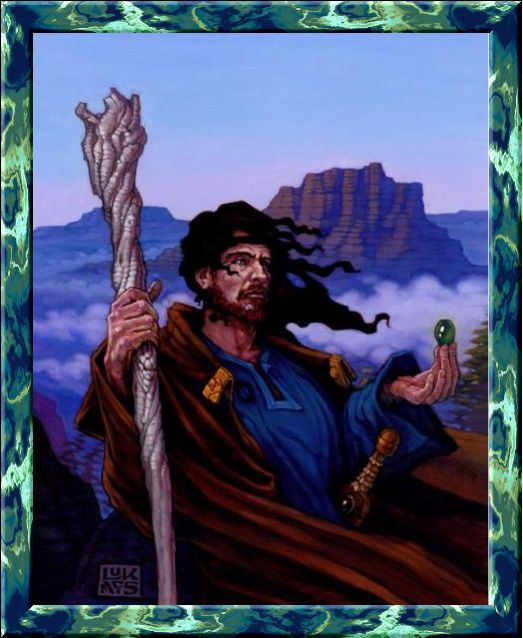

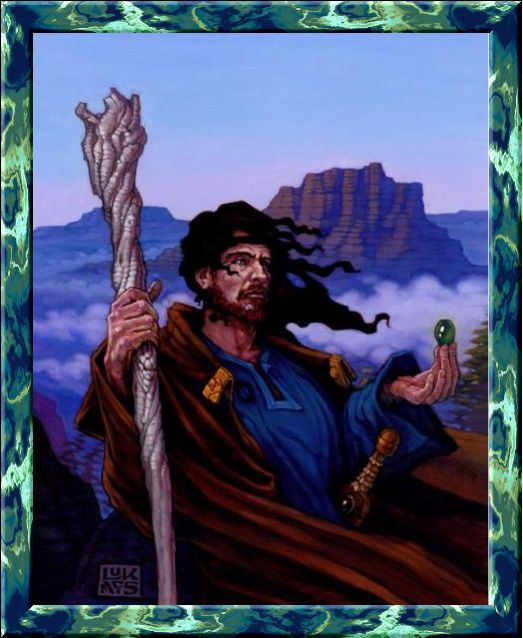

He drew his boat up on the sands and as he did, down from the hills there came two warlike men in the striped cloaks and tightly tied trousers favored on those shores. They marked well the short sword on Merlin's hip, as well as the white staff in his hands. This was in his younger days, before Merlin became the ancient sage of Arthur's court. He was tall, then, and broad in frame. His clothing was well made, but simple, being a blue tunic belted in bronze, green trousers, and a stout cloak of brown wool. His beard was short, and more brown than grey. His hair flowed in curling locks across his broad shoulders held back in a band of bronze chased with the Images of falcons. His eyes were clear and blue, and all about his person spoke of one who is strong and bold.

Because of all this, the soldiers addressed him most courteously, inquiring whether he was the one they were sent to meet by their king, who was Berach Ui Neill.

"I am the one," Merlin answered them. "And I am ready to go with you at once to meet your king."

They were surprised at this, as it was a hard journey from the land of the Britons. They expected to linger on the coast for a time allowing him to rest. But they did not doubt his word, and led him straightaway up into the deep green hills that ring that land's coasts, now dark and tinged with brown as autumn settled in. It was a steep way. Rising mist sometimes hid the narrow tracks. But Merlin easily kept the pace the two soldiers set, and they were much impressed.

Merlin himself had good reason for his haste. He left behind him his king, new to his power, and that king had given him great charge. "It is only you, Merlin, who can save me from my brother's fate," he had whispered in the deepest darkness when there was no other awake to listen to the fears of the new king. "Go where you will and do what you must. Do not leave me to die as he did."

Merlin had knelt before Uther Pendragon and sworn it would be done. He'd left him with his heart singing in its fullness. He had already seen the greatness of his king, seen it in Uther's eyes and his deeds, and seen it in the stars overheard. He, Merlin, No Man's Son would have his last vengeance. He would raise up this man and the age to follow over those who had once sought to take his life.

Burning with this ambition, Merlin walked lightly over the chill, green hills of the blessed isle.

It was near half the day before they came to the lands and houses held by Berach Ui Neill.

In those days, the men of Eire built their houses of round frames with thatch roofs of a conical shape. Simple pens held the cattle and other animals. That these were a prosperous people was evident, for the least among them wore bright gold. Even the blind man squatting by the darkened door of the smallest house had a golden ring on his thumb. As Merlin passed among the houses, all the many sounds of life and work stopped as all turned to wonder at this stranger.

The king's high house differed little from the other dwellings that clustered around it, save that it was larger in its compass, and foundations of stone bolstered its mud, lime and withy walls. But Merlin knew well it was the house of a king, and he entered it humbly and with courtesy.

A messenger had gone ahead of Merlin and his escorts. Thus warned of his coming, King Berach Ui Neill sat on his great wooden chair illuminated by a fire in the round stone hearth at center of the room, as well as the golden light of no less than ten torches set in sconces on the walls. His hair and long mustaches were the color of red gold, and his saffron tunic was banded with scarlet. A golden torque adorned his throat and a broad golden belt encircled his waist. Four great black hounds collared with gold lay at his feet. His three sons stood before him, all clad in yellow tunics and cloaked in red and blue, with gold rings on their arms and gold-hilted swords hanging from belts that were studded with jewels. Behind the king stood his wife and four daughters, all dressed in softest wool striped in every color of the rainbow. So much gold flashed on their hands, about their throats and on their brows it was as if the whole wealth of the island had been brought there to bedeck their beauty. Many of the ornaments were etched or embossed with the sign of the cross amid the workings of knots and ribbons for which that country was famous, saying that this was a people that had converted to the ways of God and Christ.

Nor was this all, for at the king's right hand waited a bard all clad in green with golden cuffs on his wrists and a white-framed harp in his hands. No less than twelve warlike men ranged the hall with their sharp spears and gilded helms on their heads. All watched the approach of Merlin Ambrosius.

Before this wealth and noble display, Merlin knelt. The soldiers who had brought him this far made their bows and retired, leaving the sorcerer alone before Berach Ui Neill.

"Be welcome to this place, Merlin Ambrosius," said the king. His voice boomed out to fill his house. Firelight set his gold ornaments and red-gold hair to shine and glitter, but shadows hid his eyes. "We are glad to receive the ambassador of Uther of the Britains."

The king gestured for him to rise. King Berach's wife came forward with a cup of gold studded with blue gems filled with the mead of that place. Merlin accepted it and drank the whole of it down in a single draught.

"I thank you for your great courtesy, king of the Ui Neill," he said as he returned the cup to the queen with a bow. "I bring to you the greetings and love of Uther who is named the father of dragons, and as a token thereof, my king commands I present to you this stone." From the purse on his belt, Merlin brought forth an emerald the size of a pigeon's egg colored the deep blue green of the seas beneath the sun. The king received this stone with great pleasure and pride. His chest swelled and his face shone to behold the jewel. Merlin's keen eye noted this and in his silence he was deeply pleased to behold, it, for it told him what manner of man was before him.

The king handed the stone to his wife, who looked shrewdly at the sorcerer. She held her peace, however, and let her husband speak. "That is a strange sword you wear, Merlin Ambrosius," he went on, displaying to all his keen and discerning eye.

Merlin smiled and drew it slowly, laying the blade out flat against his palm. "A poor thing," he said. "Once the tool of the Romans who ruled our land while the men of Eire lived freely. Bronze only, but it suits me." He held it out. "It is yours, Majesty, if it pleases you."

This puffed out King Berach's chest even further. He waved the offering away regally and then commanded that Merlin be given a bed and all he wanted for his refreshment until the feast for his welcome could be set before them. Pleased with all he had seen, Merlin permitted the king's daughters to lead him away.

The feast was conducted with all the splendor that place had to offer. Merlin sat at the king's right hand behind a board laid with cloths of delicate and brightly embroidered linen. Whole swans were brought on silver dishes, with oaten breads, as well as suckling pigs cooked in apples and sprinkled over with salt and the peppers of Spain. To drink, they had the wine of the Medeterrine and the fiery liquor the men of that isle call the water of life. There was a gracious plenty for all the company, for King Berach meant to display his wealth in his generosity. All the while the feast went on, the bard, whose name was Ailfrid mac Rian, sat beside the fire and played on his harp. He sang the great history of the Ui Neill, dwelling with the most love on the legends of Fionn mac Cumhail, the giant and king, and whom he said was greatest ancestor of the Ui Neill. If Merlin knew it to be otherwise, he prudently kept silent. Secretly, though, he watched the bard as closely as he watched the king. For Merlin knew the wisdom and secrets of the true bards, and wanted to take the measure of this one before him.

When the feasting was over, and the bard fell silent to receive the applause and praise of all the house, Merlin rose to his feet and bowed before the king.

"Majesty, I have been feasted here in a manner most worthy of the great and generous reputation that is the name of the Ui Neill. If it is your desire, I shall exercise my own humble skills for the amusement of this house, and to in some small measure show my gratitude for the rich welcome I have here received."

King Berach inclined his head magnanimously and Merlin bowed once more, very low. He stepped out into the center of the house beside the fire. Bard Ailfrid took his harp and moved aside, but their eyes met in that small moment, the bard's the pale blue of the winter sky and Merlin's the bright blue of the summer morn. Each saw secrets, and the knowledge of secrets, and each smiled a small smile at the other, knowing there would be much speech between them later.

But for now, Merlin only raised his white staff. "See then Berach Ui Neill! See then all the souls of this land! See you the workings of Merlin Ambrosius!"

He swept the staff over the bright red fire. A great wind blew cold through the house and in an instant, the flames were quenched leaving not even the scent of the smoke. All gasped in the sudden gloom. Merlin smote the earthen floor with the butt of his staff, and from the circle of ash sprang up an apple tree covered in white blossoms. Their perfume filled the house, and was so sweet that all breathed deep and sighed with the wonder of it. Merlin then raised his right hand. The tree's blossoms closed and shrank to become green fruit. He raised his left hand, and the fruits swelled, ripened and turned red. He called out a single word, and every red fruit became a red bird that took wing. All the assembly shouted for wonder. The scarlet flock flew about the house, singing songs as sweet of the scent of blossoms had been and setting all the hounds to barking. Once more, Merlin smote the earth with his staff. Birds and tree all vanished, and where they had been there burned the homely fire of the hearth.

Astonishment tied the tongues and hands of all who witnessed this miracle until the king let out a loud laugh and beat his great hands upon the table, roaring his approval. His people joined him with applause and laughter and many exclamations. Merlin bowed humbly.

King Berach rose to his feet, holding out his cup to drink to the sorcerer. "Such a marvel I have never seen!" he cried out. "What reward can I give you for such a feat?"

Merlin's eyes looked this way and that, taking in the wealth of all the hall, but more than that.

"Will you give me the hound that sleeps at Your Majesty's feet?" he asked, pointing to one of the four dogs that waited so patiently beneath the table at Berach's feet.

"And gladly," laughed the king. The hound Merlin chose was one of the great canines they breed on that isle that are prized even by the Roman lords. It was huge and shaggy, heavy jawed and black, such as might take down elk or boar. Its golden collar might make the fortune of a freeman. The king snapped his fingers and pointed. Obedient to his master, the hound loped to Merlin's side and lapped at his hand in simple loyalty.

"His name is Ciar. But surely there is more you desire?" said the king, awash in wonder and the need to show himself great in his generosity.

Merlin let himself appear to consider this as he rested one hand on the back of his new hound, Ciar. "It is not gold I seek, great King," he said slowly, as if making this admission reluctantly. "But if you would give me what I desire, you will give me an answer."

Berach spread his hands. "What answer would that be?"

"I have heard that in this land there is one of the last of the old priests, one who worked of the groves and prophecies such as used to be so common in this land. I would speak with that person."

Berach's face fell slowly into harsh lines, and the men of the house began to mutter among themselves. "We are all Christians here," said the king, but now his voice was cold. "None of this clan know anything of such a pagan witch."

Merlin cast a glance then at Berach's wife and saw how her eyes shifted away from his. He looked at Bard Ailfrid, and saw how his face remained bland and without expression. "Of course," said Merlin, inclining his head in all humility. "But this witch had a dwelling in former times, or a grove where she practiced her pagan rites. It may be that some ancient among your people might remember where that was."

"None here would have knowledge of such a thing." The king's fists hardened as he said it, and he looked about at all his company, male and female, his wife and daughters most of all. All bowed their heads and Merlin understood, He too bowed once more.

"It is surely as Your Majesty says. I ask your pardon."

This soothed Berach and restored his good spirits. He invited Merlin to sit and drink with him once more, and called upon the bard for a new song.

So passed the night until all the house was exhausted from drink and revelry. Merlin was conducted to the place set aside for him, but he did not lie down on the soft bed. Instead, he waited in the darkness, scratching the head and ears of his black hound, until all the noises of the house fell away. Then, with Ciar trotting obediently at his heels, he stepped out of the king's house, waving to the men on watch who nodded over their spears. Outside beneath the stars, he found Bard Ailfrid. Ailfrid sat with his harp, and a plate of food and a mug of drink. He played softly upon the strings, a tune Merlin had never before heard. He paused, took a bite of meat and a swig from his mug, lost in thought, then touched his fingers to the strings once more. Merlin moved aside, thinking to wait until this moment of creation was finished, but the bard turned, unsurprised to see the sorcerer come out into the chill night. The bard raised his mug and beckoned to Merlin to come closer.

Merlin sat down beside him. "A cold night."

"Ah, well." Ailfrid drank his mead and ate a piece of oaten bread.

"You could have feasted better inside." The sorcerer waved a hand at the plate and its meager offerings.

"Well enough," Ailfrid acknowledged with a shrug. "But there are nights I prefer my thoughts as company for a smaller feast." He folded his arms over the top of his harp and gazed for a moment at the autumn stars shining so brightly down.

"And may I ask, Bard Ailfrid, what are your thoughts?"

The corner of the bard's mouth twitched. "They are of you, Merlin Ambrosius, and of your errand." He traced the diamond paths of the stars with his gaze for a moment longer, before he looked to Merlin once more. "You are right in what you heard. There is such a one in these lands. She is old now, and much diminished from what she was, as are all who once spoke to the oak and the mistletoe."

"You do not fear to tell me this?" Ailfrid shook his head. "Are you not a Christian?"

Ailfrid shrugged again. "I am a bard on the edge of winter." He gazed at the darkening trees. Some had already begun to lose their cloaks of leaves and the wind rattled their bare twigs, bringing the scent of ice as well as the scent of warm smoke from the houses below. "I am what my king would have me be."

"Yours are said to be greater than kings."

Ailfrid laughed a little at this, running his fingers gently over the frame of his harp, almost as one would touch the face of a beloved child. "The greatest of us are. I am not as great as all that, and prefer a fire to the winter pride of my calling."

This answer satisfied the sorcerer, and he turned quickly to his own business, lest the bard think the better of it, or, more importantly, one of the king's men should come to overhear them. "Do you know of this priestess?"

The bard's eyes clouded over as he searched within himself. "As I crossed the borders into the land of the Fian, it grew late and I sought shelter with a shepherd family. Glad I was to have it, as the rains came down fiercely when night fell. With them was an old woman who asked for the most ancient stories, of the kings and queens of the elder days. She shook her head and sighed heavily at all I recited. When it grew late, and she and I were the only ones left waking, I asked what made her sigh so. This she said to me; 'It is all fading. The greatness of the world. Patrick and his followers have taken it all away.' I tried to comfort her, to say that the seasons would turn, and the great would rise again, but she would not hear me.

"'All gone,' she said again. 'The secrets of the earth and the future, all gone. Fionn mac Cumhail sleeps and will not wake for there is no deed great enough for him to do. The prophets have all lost their sight. None honor the priest and priestess. My own sister was called away to the druid's grove, and for years she did what was needful that we might prosper and be safe. What is she now? A wizened thing in her hut where the river Balidoire meets the bog, and none will bring her from that lonely spot for the comfort of her age.' I asked the name of this sister, so I would know her if ever I met her, and was told her name was Lasair Ui Fian."

Merlin was silent for a long time after that. He gazed at the stars, gold, blue, red and blinding white, their graceful, curving trail and mighty patterns all froze above him. "Thank you," he said at last, to the bard and the stars. Bard Ailfrid looked steadily at him, waiting. "What might I give you in return for such a good answer?"

The bard smiled and he drank his mead and ate of his meat. "Answer for answer, Merlin," he said. He folded his arms and rested them on his knees. "Her words have weighed on me since that day. You have eyes that see. Is it true what she said, that all the greatness is gone from the world?"

Merlin did not even need to look to the heavens for his answer. "It is not true. Great kings are yet to come, and long are the tales that are to be told in the world. It is written that my king, Uther Pendragon, will bring forth the greatest age of heroes the Britons shall ever know. Not one year shall go by from now until the end of days that its tales are not told."

"Well." The bard drained his mug and then stretched his long legs. "I am glad to hear it. I had thought my days short." He spoke lightly, but Merlin heard more beneath the bard's words. It was not tales he was concerned of, it was the hearts and heights of men, for such are the charges of even the least of the bards. But Ailfrid smiled, setting that away for simple pride of his people. "And if such an age comes to pass for the Britons, then how much greater will the men of Eire be? We may even wake Fionn mac Cumhail with the thunder of our striding across the world!"

Both laughed at this, making the hound raise his head and prick up his ears. Merlin touched the bard on the shoulder. "Walk your ways, Bard Ailfrid. Hear the stories and speak them with a full heart. And if ever you feel cramped on this green isle, come find me across the waters. I will show you the greatness I have seen there with the father of dragons."

Ailfrid looked at him for a thoughtful moment and for that moment, Merlin could not read what was in the other man's heart. "Perhaps I will," said the bard. "If only to return home and sing of these great heroics your King Uther is to bring forth." Ailfrid stood, taking his harp tenderly into his arms. "I wish you well in your errand, Merlin Ambrosius, but perhaps you'll accept one word from me."

Merlin spread his hands. "And what word is that?"

"My kind must go about on foot, and here is a thing we all learn; be sure you've looked long and hard at the path where you step before you declare you know your way along it."

With these words, the bard took his harp back into the king's house. Merlin sat awhile beneath the stars, pondering the lights and the words, and the errand which brought him there.

Merlin Ambrosius stayed seven days with Berach Ui Neill. To stay less would be to insult the hospitality of a king. They talked of many things, but mostly of those men of Eire who settled in the north of the Briton's land, and how peace might be got between them and the more southerly lords. When Merlin spoke again with the bard, it was only of small matters, and small stories.

At the end of his stay, the king bid Merlin a courteous farewell and gifted him with a gold-hilted dagger to hang beside his sword. The sorcerer was given a good escort of six men to walk him to the borders of the Ui Neill lands. There, the men turned back to their homes, and Merlin Ambrosius and the great hound Ciar walked on, Merlin wrapping his cloak tight about himself, for even in the brightness of the day, the winds were grew cold.

The blessed isle may be likened to a great bowl floating on the ocean. All its steep hills and mountains ring its coasts. Once beyond their heights, the land rolls and slopes pleasantly downward and one may walk beside pure streams of running water through forests of mighty oak and ash, bountiful hazel and apple. But when one reaches the center, one finds all the waters have mixed and mingled and settled together to create black fens, dark as night and more foul than any midden. Their miasma hangs heavy over them, breeding disease and disaster. The secret lights inside lure travelers from the narrow paths and bridges so that they disappear forever. Only the poorest people cling to their edges. Those without king or clan or any other protection eke out sad lives beneath the towering trees that are fed by the black waters.

As he began the downward slope, Merlin came to a place where three streams crossed each other, mingling into one. He took Ciar's golden collar and tossed it into the river. Then, he dipped his staff into the waters and he said. "In the name of the mother of all the waters, are you the river men call Balidoire?"

And from the river came the answer. "I am that water and I will take you where you need to go."

So, Merlin walked on.

Merlin followed the path of the river and the fall of the land down through the great forests and meadows of deep green. When men stopped him and asked his business, he was always careful to give courteous answer, and to have a token gift of silver ready for whoever they named as their king. Whether these gifts found their way to these kings, Merlin neither knew or cared. He cared only that he was allowed to go his way unmolested.

At last, the land's slope gentled and the rolling hills spread out and smoothed. The air over the land took on the tinge of sulphur and death, growing warm and close despite the deepening of the autumn. So it was that Merlin knew the darkness before him was the great fen. The Balidoire, his good guide, spread out as well, growing flat, slow and murky where before it had been sprightly and silver. The trees huddled closer together, dipping their branches down to catch at his hair and clothes. Even his stout hound grew uneasy, alternately growling at the strange noises and pressing close to Merlin's side. Merlin patted the hound and urged him along, but he also kept tight grip on his white staff.

At last, through a grove of willows, mangy with autumn, he saw a thin stream of smoke rising in the fetid air. Beneath it hunched a small hovel. The house was so low and covered so much in turf that it might have grown there rather than been raised by the hand of man. Even Merlin's eyes would have missed it were it not for the smoke.

Merlin stopped some small distance away, and commanded Ciar to sit peaceably beside him. "I salute the house!" he called. "I seek Lasair Ui Fian, and would speak with her if she is here!"

He waited patiently. The birds and the frogs made their calls to one another. The waters muttered at his feet, and the trees whispered overhead in the cold, foul wind. Then, slowly, he heard a different rustling and saw movement within the darkness of the house. The blanket hanging over the low doorway moved aside and out crawled an old woman.

She was filthy beyond description, more a creature of mud and earth than of flesh. Her clotted hair was white beneath the grime and stuck out wildly in every direction. It was impossible to say what color her ungirded garment had once been, but now it was streaked green and black. So thin was she that Merlin could see all the bones beneath her skin, and her fingers were delicate twigs. Her eyes were still clear and green, but as he saw the pain in them, Merlin's heart was moved to great pity.

She smiled, a horrible gaping grin that showed her shriveled gums and single tooth. "And what is it you seek here, a fine man such as yourself?" Her voice cracked and wheezed as she spread her bony hands and tottered toward him. Her legs were bare, her feet black with muck. and her odor that of the fen itself. "Is it a love charm, perhaps?" She leered. "Some pretty young thing not sure that a man of silver as well as gold is up to keeping her fat and full?"

Despite his pity and his horror, Merlin kept his countenance and bowed low. "I would not presume to bring such a matter before you, reverend one, mother of the oak and the mistletoe."

Lasair Ui Neill stopped where she was. The leer drained from her lean face and her arms fell to her sides. "That is not myself," she said, wagging her head. "That was long ago."

"Not so long ago. A moment. A fold of years."

"Stop!" she cried, her voice suddenly so strong and clear, that Merlin raised his brows. "That is gone, I say." She jabbed one long finger at him. "Gone, and better so."

Merlin looked about at the yellowing willows and the waiting fen. He looked at the low house and breathed in the stench of the air. "How better, reverend one?" he asked quietly.

She closed her mouth, and he saw again that for all her face was ravaged by time and hardship her eyes were as clear as the streams flowing down the slopes. "Better hidden than destroyed," she said softly. "Better sleeping than dead." Her jaw hardened and her shoulders straightened. It was as if twenty years slipped from her, and he saw how well she had perfected her disguise. "You are one who sees, fine man." She spoke judiciously now, looking him up and down. "I can still tell that much. You know the time loops around itself, and all things come again to their beginnings. The age of miracles will come again, and the voice will be needed to speak once more."

Merlin let out a long, slow breath. "That voice does still exist then."

Slowly, she nodded, all guile, all terrible humor gone from her. "For those who can find it and hear, yes it does."

"The way to hear that voice must be greatly secret."

At his words, her leering smile returned all in a moment. "And you'd know that secret would you, with your hawk's eyes and your heart greedy for knowledge?" She tapped his breast with one twig-finger, and when Merlin looked disconcerted, she laughed.

Merlin hung his head, as if bested. At his feet, Ciar whined to see him distressed. "I will not lie," said Merlin. "Yes, I would know it. I have walked and sought long to find it."

"Ha!" Lasair Ui Fian stepped back, and squatted down in front of her door, settling the mask of the hag once more over the priestess. "You'll not have it here. It is all that I have left." She looked past him, up the slope of the woods, toward the places where men lived in their snug houses. "Even that fool girl who swore she wanted to study with me left when Patrick and his band came tramping through singing of their White Christ. My last acolyte, she ran away with them." Bitterness soaked her words and Merlin saw the hard glitter of tears in her eyes. "And it was all gone, all of it, save the voice that sleeps and waits."

Merlin moved forward. Laying down his staff, he knelt before her. "If you would have a acolyte, I would learn from you."

She gazed at him, and hope shone behind the glittering tears, but only for a moment. She dropped her gaze, and picked at the browning grass between her feet with her twig-like fingers. "No, you wouldn't," she muttered harshly. "You don't want to learn. You want to know."

On his knees, Merlin leaned forward. He pitched his voice soft and low, a lover's voice, a seducer's. "And were you the one to bring me that knowledge, your name would be made great," he said softly. "You would come to a land of honor and plenty and be given rings by the greatest of rulers."

Her restless hands stopped their meaningless scrabbling and she lifted her gaze. "Look at me, man."

Merlin laid one hand softly on his staff. "Look all you want," he told her. "See whatever you wish."

Her eyes were green as the heath in the sunlight, and both older and younger than herself. Merlin felt the power of her gaze reaching deep, running along the well-worn grooves of truth and possibility that lay within her heart, and his. "You stand beside kings," she spoke dreamily, in the way of the oracle. "They are brothers these kings. Mighty men, both. They are not to be defeated by honorable means. One is gone now, taken by stealth and by poison. The other, he is greater than brother or father ever were, but fears the poison. He shakes in the night with fear of it and he knows that fear cripples him. You cannot bear to see this fear for you know the greatness of the man. He is brother in your heart, but he is your vengeance too. Oh, yes, your vengeance and your triumph is this father of dragons. He sent you here. You told him the means to guard against fear and future could be found in these hills. You come to walk the ancient ways. You have heard the old names and the old wisdom. You would drink from that fountain at my hands . . . there is reverence in you . . . you understand the deep roots . . . you . . .

"No!" she shrieked the word, throwing herself backwards into the folds of the blanket that covered her doorway,

"Lasair Ui Fian, look at me!" commanded Merlin, seducer no more.

"Liar!" She screamed, scrambled backwards, her blanket falling about her ridiculously. "You try to hide your heart behind your eyes but even you cannot hide so deep."

"Look at me, and you will see the truth," Merlin grasped her wrist and its bones dug into his palm. "You can see. Your power will show you the truth!"

But she tore herself away with a strength he would not have guessed she had. "Yes, I am shown the truth, hawk-eyed man!" she spat. "I see you know where power lies, and you come to claim it." She huddled beneath her blanket, drawing in on herself, holding all she knew behind the walls she had built within her soul. "You hide too much too deeply, and will one day be hidden from all seeking. Oh, yes." She grinned again, the horrible gaping leer with which she had first greeted him. "It is true I am not blind. I see the long darkness." Her voice fell, growing low as her eyes grew distant. The blanket slipped from her grip, dropping to the ground. "The age, the time of the world creeping by, the worms seeking and seeking but gaining nothing from your flesh. Frozen, trapped, eyes fixed on a single point as the flies gather and the waters rise and fall and . . ." She stopped, swaying on her knees, her eyes blinking. She raised her hands, brushing aside nothing he could see. Then, her ruined face broke into a scowl of unbearable fear. "Get away from me!" she screamed at him, her trembling arm reaching out to sketch old signs of warding. "Demon! Death bringer! Get away!"

Screaming, she scrabbled back into her house, diving beneath her blanket. Merlin did not try to follow her. He stood and he bowed to the trembling, weeping form he could no longer see. With a word to Ciar, he walked up the slopes into the woods. Only when he was sure he was out of sight and hearing of the hovel and its ancient occupant, Merlin turned and squatted on his heels before his hound. Gently, he touched the tip of his staff to the beast's head.

"Now then, Ciar. There was a girl in that house with the old woman. She left sometime ago, and I need to know where she went. You caught her scent, good dog, I know that you did. Will you find her for me?"

The dog looked into Merlin's eyes for a long moment and then barked once, a cheerful, agreeable sound. The sorcerer stood back, and let the hound nose about at his feet for a bit. Then, Ciar barked again and loped off up the slopes on a straight and steady track that none but himself could see.

Smiling to himself, Merlin followed the dog into the woods.

For three days Merlin followed where the hound led. They crossed streams and rivers and trekked through many fair woods aflame with the colors of autumn, always upwards until they reached the windy heights of the western hills. There, he came to a small dwelling-place, well fenced, with a cross hung upon the archway of its gate. Just outside the gate, a stout woman with a wagging dewlap tended a flock of grey geese. She wore a plain brown cloak over a simple white dress girdled with braided leather. She had her hems tucked into the belt, exposing her sandaled feet, and bare, thick legs. Her only ornament was the wooden cross hung on a thong about her neck. She glowered as she saw him approach with his loping hound. Merlin patted Ciar and commanded him to sit a distance away while he approached the woman.

"God be with you, Sister," he saluted her.

"And with you, stranger," she said, but there was no sincerity in the greeting as she took in his face, his sword and his staff. "And what brings you to this house?"

"I am seeking a woman of the Ui Fian here."

She squinted at his face again, and shook her heavy head. "No one such as that here." One of the geese honked and waddled away from the rest of the flock. The woman flicked her switch, and the bird meandered obediently back. "The only ones here are daughters of Christ."

"It may be she took a new name when she came to Christ," said Merlin patiently. He leaned heavily on his staff, showing more weariness than he truly felt.

She shrugged, but did not turn her attention from the geese. "It may be. Many do."

"May I have leave to inquire after her with the other sisters?"

That made the goose-woman turn to him, as he had known it would. "We are a house of women here. You are not of the brethren of Christ," she snapped the accusation and accompanied it with another hard look. "You have no foundation to enter here."

"Forgive me, Sister," Merlin replied, bowing as humbly before the goose-woman as he had before the king. "But I have walked a long way, and my errand is urgent."

She narrowed her eyes. "Who are you that you come to claim her?"

Ah. Now he understood the hostility. Even now that most of this isle followed the Christian rite, there were many families who were less than pleased when their marriageable daughters declared their intentions to join a poor house of women and live the life of a perpetual virgin. "I do not come to claim her, only to speak with her."

"But who are you?" demanded the goose-woman again.

Merlin spread his hands. "I am not brother, nor son, nor husband, nor father, nor chief, nor master. I am only another seeker who would learn what she can tell me. Herewith, is my token to the maintenance of this place and this house." He reached into his purse and held out two silver rings.

"Hmph," grunted the woman, but she took the rings and tucked them into her sleeve.

She peered at him again, and Merlin spoke mildly, leaning there on his staff. "You see, I have no bad intention, nor do I mean to trouble this house. I only wish to speak with she who was once the daughter of the Ui Fion, who turned aside from witchcraft to come to Christ."

The goose-woman grunted again, and then said, "There is a woman of the Ui Fion here. Her name is Agnes now. You may wait while I see if she's about. Don't let the geese stray." She stumped through the gate.

Merlin settled onto his heels to wait. Patiently, he watched the grey geese, who honked and chattered and pulled at the weeds and preened, and did not one of them stray from their patch of grass where their mistress left them.

On the other side of the fence, the sisters of the house passed to and fro between the buildings. All of them, the old and the young, dressed alike in their simple white robes and brown cloaks and wooden crosses. They stared, perhaps longer than was courteous, at the man tending their geese. But Merlin made no move to speak to any of them, nor for a moment did he neglect the task to which he had been set.

At last, the goose-woman returned. Beside her walked the sister now called Agnes. If she was truly a girl as Lasair had called her, she had left that girlhood behind years ago. She was a square woman, her aspect bespeaking strength rather than beauty. Her hands were large, and her face was tanned and lined as one who worked hard and did not fear to do so. Despite this, she looked at him with apprehension bordering on alarm.

"I do not know you," she said, hanging back.

Merlin straightened, his knees popping as he did. He bowed. "I am Merlin Ambrosius, and I am come from the land of the Britons and the king Uther Pendragon only that I may speak with you, Sister."

Agnes clenched her jaw, clearly not knowing what to make of this. If the flattery touched her, it was brushed away by her uncertainty. "What could such a one have to say to me? I am no one."

Merlin smiled at this modesty and glanced at the goose-woman. "If I may have a word with your sister privately?"

The goose-woman considered this, but nodded. "Don't fear him, Agnes," she said to the other woman, laying a reassuring hand on her arm. "I'll be here if you've need of me." And she stomped back to her geese, where she would no doubt count them carefully to make sure he had done his work well.

Agnes faced the sorcerer, her eyes cast down and her fingers tightly laced together. She said nothing.

"I have been to see your former teacher," ventured Merlin.

At these words, Agnes glanced upwards, but dropped her gaze at once. "How does she?" she whispered hoarsely.

"She is old, and lonely," replied Merlin gently, trying to catch her eye.

Agnes sighed and twisted her hands more tightly together, looking away down the rolling slopes toward the distant fens, even as her teacher had looked up those same slopes. Two longing gazes missing each other for the want of time and faith. "I am sorry for her." Some memory had her snared, and Merlin strained to understand what it might be. "If she were to renounce her pagan ways and follow Christ, we would gladly care for her here." They were pious words, and deeply felt, but there was something else, something old and secret locked away.

Merlin nodded in sympathy at her words. "Alas," he said, twisting his staff as she twisted her hands. "There is another power that holds her."

"What do you mean?" Curiosity made her flick her eyes sideways toward him.

Casting a glance over his shoulder at the goose-woman who now stood with her broad back to them, Merlin took a step forward. "She still believes she guards the voice that waits and sleeps," he murmured. "While she remains sure of that, she will never turn to a new path."

The wind blew hard and cold between them. It smelled of rain and of the distant ocean and the damp rot of autumn. "I believe that you are right," said Agnes. The words were nothing, polite agreement with a stranger, nothing more. She was caught in other memories. They thronged thick behind the eyes she would raise to him only for the barest second. Memories perhaps of her leave-taking, or of the years before and since.

"Were the voice to be silenced, it would no longer drown out the voice of God in her ears."

Agnes swallowed, her face sad and sober. Merlin realized she had thought of this before. "I will turn my prayers to it." Again, a politeness, a nothing. She wanted him to leave her, to not remind her of other times and places.

"Sister," said Merlin as gently as he had ever spoken in his life. "I am come to silence the voice, but I do not know how to find it. Do you?"

Look at me. Look at me, he commanded silently. But she did not. Agnes only looked at her hands, laced so tightly together. The wind tugged at her graying hair, teasing out elf locks to hang around her ears. "I cannot tell you that," she whispered.

"Cannot or will not?"

She bit her lips. "I swore I would not." Her voice grew stronger, and Merlin cursed that strength. "When I heard the word of Christ and chose the virgin's path, I swore before God that I would not ever tell what I had formerly known." Her eyes were bright with the glimmer of tears, and Merlin remembered the tears that had also been in Lasair eyes. "It was only that oath that made her let me go."

Merlin mustered all the patience he had. If he faltered now, all would be lost. The barest hint of anger or impatience would harden her against him. "How can you hold to an oath that keeps her from God?"

Agnes lifted her head. "Because I swore," she answered and for the first time Merlin heard in her voice that strength which was so evident in her form. "Because she was mother and teacher to me for many long years. It would be sin not to keep my oath to her. God commands we honor mother and father."

But she looked at him, and he could hold her gaze now. "God also commands you destroy the ways of the pagan, sister. How can you refuse this battle for her soul?"

He reached for her, willing her understanding, her acceptance of what he said. But to his astonishment, she only glared at him. "I swore my oath. I will not break it."

Agnes turned on her heel and marched back through the gate. Merlin made to follow, but at once, the goose woman was in front of him, as if brought there by magic. Merlin looked into her stern aspect for a moment, and then bowed, retreating to the edge of the fence. There, he sat down, laying his staff across his knees, and prepared to wait.

The goose-woman stared in astonishment at him. Then, she turned her back, and tried fair to ignore him, though she cast many a disapproving glance in his direction. Merlin was not surprised that she took no further measures. To sit beside a doorway in patient fast was a gesture she would understand well. It had been used by petitioners to kings of Eire, and to stubborn brides. Usually, all that had to be done was to wait until the petitioner, ignored and humiliated, was driven away by cold or hunger.

The women beyond the fence came and went, rustling and whispering. Evening came, and the cold night afterwards. Clouds thickened, and rain came. Ciar whimpered and pressed close to Merlin. Merlin scratched the hound's head and patted his side, and they shivered together without fire.

The morning came like a blessing and the fading autumn sun dried them both. Hunger tightened Merlin's belly. Thirst parched his throat. But still he sat where he was and waited. The day passed. The women came and went behind their fence, much as the clouds scudded across the sky. The rains fell, and the sun reappeared. The cold deepened as night drew near. Ciar whimpered and barked. After awhile, he disappeared and returned with a sparrow in his mouth, which he dropped at Merlin's feet. He nosed at his master's hand, urging him to eat the offering. Merlin patted Ciar's great head, and waited.

When the first blue flush of twilight crept across the sky, Sister Agnes came to stand before him, hands on her hips and the flash of steel in her eyes. Merlin inclined his head to her.

"Leave here," she said flatly.

Merlin lifted his eyes. "I will leave when I have learned what I need to know," he croaked.

"You will starve then," she told him.

Merlin shrugged and rested both hands on his staff. "Then I will starve."

Agnes hissed wordlessly in her exasperation, and left.

So, the night came, and more rain with it. Merlin, despite all his strength of mind and training of body shivered beneath his cloak. He drank the rain as it fell, and as it ran down his face and fingertips. Ciar whined and trembled and would not leave even when Merlin commanded it, but only rested his head on his master's knee. Merlin threw the end of his cloak over the dog, sharing what pitiful warmth there was. Wolves howled unseen in the forest, making the dog growl and bark in answer.

Morning came cold and grey. Mists rose in clouds and columns from the valleys and the folds in the hills. Once more, Sister Agnes marched through the gate. This time, she held a round loaf in her hand.

"Look, here is bread." She held the before him and broke it in half so that the steam rose and warmed his face, bringing all the delicious odors of the oaten bread with it.

Merlin licked his lips, searching for some hint of moisture still there. "It is not bread I came for."

"You cannot sit here until you die." Beneath the annoyance he heard what he waited for. Worry had returned to Sister Agnes's voice.

"If I must, I must, for I cannot leave." He made himself shrug.

"I will not break the oath that set me free!" She cried, the force of her words straightening her back.

Mustering his strength, Merlin lifted his head and met her gaze, seeing how anger and concern warred within her. "Then your silence will be my death."

She dropped the loaf on the ground, turned and left, walking too fast, not looking back. Merlin pushed the loaf toward Ciar. The dog whined and thumped his tail, and ate the bread. Merlin hoped that Sister Agnes saw this, or that one of her sisters did, and would tell her truly, but could not turn his head to see.

Another day and another dragged past. He shivered uncontrollably now, as if a fever wracked him. His cloak only dried slowly. Hunger and thirst became dull aches within him. His legs alternated between a cold numbness and a storm of prickling and heat burning through them as if his blood were made of pins. When darkness enveloped the world, the wolves moved closer now, and he could see their eyes shining in the bracken that edged the forest. Ciar's hackles rose and he barked sharply, stalking forward, warning them with his bulk. They crept away, but they would return. Both master and hound knew it, but there was nothing to be done. Merlin dozed fitfully in the frigid darkness, dreaming many strange and troubling dreams, only to pry his eyes open at the grey dawn and Ciar's bark, and look up.

Sister Agnes stood before him, her square face white and pinched. Her brown cloak was laced tightly against the cold, and she bit her lips as she looked down at him. She carried a bowl of water, a haunch of bread and a blanket of undyed wool in her hands.

With a groan, Merlin pushed himself into a sitting position, and dropped one hand across his staff. To his shame he was not sure he had the strength to lift it if he had the need. The relentless cold had robbed him of all such power. It seared a path down to his lungs even now as he tried to breathe.

Agnes knelt beside him, laying the things she'd brought in her lap. She made no greeting, but only leaned close to him. "Is it true what you said? It is only the voice that keeps her from God?"

Merlin nodded, and his trembling increased.

"I have prayed long over this." She bit her lips again. "I sin, no matter what I do, but if what you say is so, then I cannot let my mother and teacher die without baptism when my actions might bring her to God." Her voice eased and strengthened. "I will tell you what I know."

"All you know?" he whispered. "You swear it?"

"All I know, and I do swear."

Merlin closed his eyes and reached one shaking hand for the water bowl she brought. He drank long of the clear water as Sister Agnes threw the warm blanket about his shoulders. She helped him tear and soften the bread so that he might eat of it. Slowly, the strength returned to his limbs and the clarity of thought to his mind.

When his trembling had ceased, Sister Agnes, bent close to him, whispering so that only he could hear. "This is what she told me, and I swear before God this is the whole of it. She told me that atop the tallest mountain of Beanncarrig, there stands an ancient tomb. Anyone who stands inside at dawn on the day of the new year will see a door. At that moment any who asks for entry in the name of the one who raised the tomb will be able to open that door and follow the path downward. He will pass three more rooms, and three more doors. The first is opened with a truth, the second with a lie, the third with all he has. Inside the last room is the voice and the blessing, and all questions will be answered there."

Merlin closed his eyes, in weariness and in gratitude. "Thank you, Sister Agnes," he murmured. "May God bless you."

She gathered up the bowl and blanket, all of her uncertainty coming over her again. "Come to me on your return and tell me I may go minister to my old teacher." She stood hastily, making to depart. To pray, Merlin thought, to try to make peace with what she had done.

"Will you care for my dog?" Merlin asked abruptly. "He cannot follow the road I must take."

She looked at the great black hound, thinking perhaps of the geese and the sheep, but also of the wolves that howled in the night. She nodded. "Go with God then."

"I thank you, Sister."

Leaning on his staff, Merlin got himself to his feet. With only slightly more difficulty, he persuaded Ciar to follow Agnes through the gate. He watched them both go with something like regret, but then turned his face westward, looking toward the taller mountains waiting there.

With a sigh, Merlin began once more to walk.

It was a long walk, for he must husband his strength. But the cold that was deepening the sky and the wind both told him the eve of the new year quickly approached. With this knowledge driving him, Merlin hurried as much as he dared. He clambered over the rocky slopes by day, finding much to drink but little to eat. He lay down beneath thick blankets of leaves at night and woke to find frost on his hood and ice in the streams that sustained him. Cold stiffened his hands and his legs. His breath came out in white clouds when the weather was clear, and in harsh gasps when the rain poured down. There were none up here to witness his passage, but neither were there any to offer him shelter. By his art he had fire at night, but not all the power he knew could keep the rain from his back without a roof and the higher he climbed, the more sparse the forest became, until there were not even branches nor leaves to help shelter him.

Bent almost double from the steepness of the climb, Merlin came at last to the height of Beanncarrig to see the tomb just where Agnes said it would be. It was an ancient place, sturdily built after the pattern of the dwellings of the living-a huge round house of stone with a conical roof of timbers, lime and slate. A stone cross thick with carvings of knots and ribbons stood before it, but that was a new thing compared to the tomb itself, and the carvings on its walls showed as much. Here were the ribbons and the knots, but no sign of cross or Christ. On the sides of the tomb Merlin found the white mare and the raven, the salmon, the bull and the boar. The horned god held court there and the goddess rode in her chariot.

If there had once been a portal set in the stone threshold, it had long since rotted away. In its place now waited two tangled thorn bushes, their barbs thrusting outward. Merlin broke off a small twig from one and tucked it into his sleeve as he made his way between them, careful to break no other branch nor tear off any of the dying leaves.

Inside the tomb was only darkness. The clouds hung so low and so thick outside, no sun streamed through the doorway. The air was dank, still and cool, with only the lightest draft to touch its fingers to the back of Merlin's neck. Before him in the gloom, he saw the dead.

They lined the walls laid out in carved niches, three high. Their names had been carved there in the oldest runes of all. They had been there as long as the tomb, these corpses, and now were nothing more than bones beneath shrouds that a breath would have turned to a shower of dust. Still, they waited, grey bones, ruined cloth and empty eyes. Here and there a jewel flashed or a ring of gold on finger bone or wrist. Merlin touched none of this. By his art, he made himself a fire and sat beside it. He ate some of the nuts and withered apples he had gathered on the lower slopes, and then stretched out before the doorway to sleep. He missed Ciar's solid warmth beside him but rolled himself in his cloak and let exhaustion carry him away.

The hooting of the first owl woke Merlin at dusk. He came to himself instantly, and picked up his staff. The owl called again, a low, warning sound. He quenched his fire and faced the doorway. The wind had picked up outside, rattling the thorns in front of him and sending a new draft to wrap around his throat and ankles. The owl called once more, searching, hunting.

Behind him, the dead rustled beneath their shrouds. Bone clicked against bone, skulls in their niches ground their jaws. The wind picked up their fear as if it were smoke and brushed it against Merlin's skin. It was old fear with roots that pushed their way beneath his skin.

"Rest, my friends," said Merlin kindly. "Rest, all of you. It is not time to rise yet."

It calls us, said the dead in their silent way. The root of their fear grew thicker, fear of being called away, of being lost, forever lost, they who truly knew what eternity meant.

"That call is not for you," Merlin told them, taking firm hold of his staff. "Sleep now. You have earned that sleep."

Slowly the clatter faded and the rustling turned again to silence. A wolf howled in the distance and Merlin lifted his head to the sound. "Not here. Not tonight," he said to the darkness. "Find some other to steal. Tonight, all sleep here under my protection."

And neither beast nor bird spoke again in his hearing. The wind was only cold, and the dead settled back to their deep and dreamless sleep.

Merlin kept watch over the doorway, helping the thorns stand guard for that long night. He was still weak from his fast and his long travels, but he kept hold of his staff and did not let sleep claim him. Gradually, he became aware that the world beyond the thorn trees had lightened. He stood, stretching himself and he bowed in greeting to the coming dawn. As if in answer, the sun let loose a single shaft that pierced the tomb. Merlin jumped back from it that he would not divert its course. On the curving western wall, he saw a stone door glowing golden in that single shaft of dawn. With a glad cry, Merlin ran to it at once and pressed his hands to it. He had just time to make out the portal's faint lines, but could see neither latch nor handle.

Then the sun was gone, and his eyes could see nothing but the carved stone wall before him. Beneath his palm, though, he felt the hair fine crack where the door fitted to wall.

Then, he spoke the words he had carried all the way from the West Lands. "In the name of Oisin mac Fionn, son of Fionnn mac Cumhail and Sabha of the leahaun sidhe, son of Cumhal mac Trenmor and Muirne of the white neck, I beg you, open this door and permit me entry."

He took a deep breath, and lowered his hand. He waited one heartbeat, two, three. He waited long enough for fear that he had been hopelessly wrong to seize tight hold.

Then, soundlessly, smoothly, the barrier before him drew back, leaving in its wake a patch of blackness deeper than the night. Merlin swallowed, his knees suddenly weak with relief. Hurriedly, he drew the dagger he had been given from his belt and thrust it deep into the earthen floor beneath the threshold. The dagger was steel, the close kin of cold iron, which was the metal proof against enchantment. Its presence would keep him from the path ahead if he tried to carry it, but left here, it would hold this way open until he returned.

Holding tightly to his staff, Merlin marched forward, and did not look back.

He had no sense of descending. The floor beneath his boots was utterly smooth, as was the curving wall beneath his fingertips when he stretched out his hand. But with each step, he felt the distance between him and all that he had known grow greater beyond all reason. His eyes strained until they ached, and at last he perceived a tiny speck of white like a star in the distance. He walked on. Each step was a league, each breath a day. All his weakness came down upon his shoulders. All behind was darkness, the only light was up ahead.

A new draft of air wafted past him. This too came from the way ahead, but where he expected the odor of earth and mould, he instead found the welcome scents of green and growing things and the warmth that only comes from sunlight. Amazed, Merlin urged his steps forward.

He emerged from the tunnel into a mighty forest at the height of summer. Trees towered on all sides of him. Light fell in long shafts of greenish gold lighting up the ferns and brilliant white and blue blossoms. If this was a cavern, the walls and roof soared so far away they were lost in the sunless light. The air was warm and clear and rich with the scents of the blossoms and the whole living world, but no bird sang, nor was there any other sound of animal life here. The quiet unsettled Merlin, and he laid his hand on the hilt of his sword.

Then, the bracken before him cracked and rustled, and a tiny man pushed through the drooping leaves. He was only as tall as Merlin's knee and as brown and twisted as tree roots clothed in moss. Merlin stared, amused, but wary, and his hand did not move from his sword's hilt.

The creature climbed nimbly up onto a rotting stump and squatted there, gazing up at the sorcerer with bright black eyes.

"You cannot pass," he piped shrilly. "Go back the way you came."

Merlin struggled to maintain his countenance, and bowed courteously to the little man. "I beg your pardon and I mean no offense, but I must pass. There is a door beyond here which I must open."

"You cannot pass," the brown man said again. "Go back or I'll set my cat on you!"

"You will do as you must," he answered gravely. "And I will do the same."

Setting his eyes on the way ahead, Merlin walked through the pleasant wood. He felt the gaze of the little man at his back, and he felt the trees lean in close, waiting, it seemed gloating, ready for the entertainment that was to come as he walked more deeply into their presence. The whole wood held its breath around him, silent, expectant.

He had not gone more than ten paces when he heard the little man shout, "Cat! Cat! Here is a mouse for you!"

Overhead, the leaves rustled. Merlin threw himself sideways. His staff spun from his hand, but he let it lie. A black blur dropped into the place where had stood. He righted himself, drawing his sword, the bright bronze blade that had once belonged to a Roman soldier. With only this as a barrier, he found himself face-to-face with a great cat, the size of the lion of Africa, but coal black in color. Its eyes blazed bright green as it snarled at him, showing all its ivory white fangs.

Merlin did not wait for the cat to lunge, instead, he leapt forward, aiming his stroke at the creature's throat. It dodged his blow, agile and quick, screaming at his temerity. Merlin turned and the cat stalked around him, tracking his movement, its hackles raised, watching the strange and dangerous mouse. Merlin lunged again, and this time the cat leapt to meet him, sinking its fangs deep into his shoulder. The sorcerer cried aloud with pain as the cat bore him to the ground, its claws digging deep into his chest and thighs. Blood and pain seared like fire and Merlin screamed to shake the world. But even as he fell he thrust upward with his sword, and that bronze blade found the cat's flesh. Now the beast screamed in agony and outrage. It scrabbled backward, scoring him over and again with its great claws. Merlin lashed out blindly, and the cat screamed once more, and the strange clank of metal against metal rang through the forest.

Breathing hard with the pain and awash in his own blood, Merlin pushed himself to his feet. He stared, his wounded left arm hanging loose at his side. The cat was limping backward. He had wounded it, in the leg and in the side, but instead of blood fat coins of shining gold dropped from those wounds.

Merlin reclaimed his sword. Gritting his teeth hard against the pain, he ran forward three steps and stabbed his blade into the flank of the retreating cat. He slashed sideways, opening a great gash in the black hide. More golden coins poured out, clinking and clanking and shining, raising a scent of hot metal in the forge. More than in the treasury of all the kings of the blessed isle poured out in that grotesque golden fountain. The creature screamed out once more, staggered, and fell dead. Under Merlin's astonished gaze, the black skin began to shrivel and fall back, as if the work of a hundred years beneath the soil was accomplished in a dozen breaths. The two eyes fell from the monster's skull. Each was an emerald the size of a baby's fist. One would have bought the emerald he'd brought to King Berach a thousand times over. Two would buy the whole of the blessed isle. Both now lay among white bones and golden coins.

"Well, it is yours now."

Painfully Merlin turned his head to see the little brown person sitting hunched beside the closed door.

"You've killed my pet, my rare one," the little man said sadly. "I did not think it could be done. Take the gold and leave me to bury her."

"It is not gold I want." Trembling, and gritting his teeth against the pain, Merlin limped back to his staff and reclaimed it. His hands shook, and his legs threatened to give way. He noted, distantly, that the forest floor drank his blood and the cat's just as thirstily.

"Ha! All men want gold."

"No." Merlin shook his head heavily. Pain made his reason swoop and spin within him. The bleeding was bad and he could not feel the staff he held. He needed to rest, to heal himself. But not here. Not yet. "No thing I have ever done has been for gold. Nor will it."

The little man regarded him keenly, and then nodded. "So it is. Go on then, man. See what you have to say to the next you meet." He nodded toward the trees. Now, Merlin could see that the cavern wall was quite close. The veil of hazy golden light had lifted from it, and in the living stone of the wall waited a portal of wood banded with bronze. Even as his blurred eyes made it out, the door fell open to reveal more darkness.

Merlin shuffled forward. His wounded legs did not want to move. His left arm could not hold his staff and he cradled it close to his chest. The blood ran down in scarlet streams and his sight swam before him. It seemed an age before he reached the blessed blinding darkness. There he leaned against the cool wall and did nothing for a moment but breathe and weep from the pain. Then, he made his left hand wrap around his staff with his right. In a harsh, hoarse voice, he spoke certain words known to him.

Fresh pain blasted through him like a lightning stroke. It seized flesh, blood and bone, twisting and compressing them tightly. His heart hammered, and he could neither breathe nor see for a long moment.

Then, it was over. Merlin pushed himself away from the wall. Blood still coated his skin and clothing, but it no longer flowed fresh. Any who had seen him then would have thought him unscathed. But Merlin knew his wounds waited close beneath the surface of his skin. This was no true healing such as only God and time could make, but it would serve for the moment, and enable him to walk again through the darkness, although the pain pulled at him with each step.

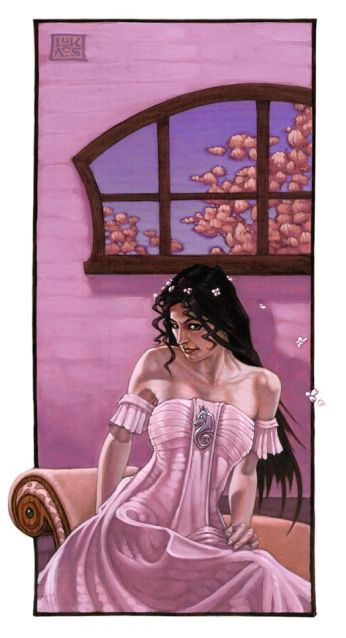

After a time that was both far too long and far too brief, light opened again around him. Merlin blinked to behold the new world he entered. Where the chamber before had been a wilderness, this place was a garden. Its tall trees and broad lawn all seemed lovingly tended. A profusion of flowers perfumed the air with a thousands scents. As he stood and breathed them in, Merlin felt his heart lift. The strength of his limbs increased and the pain ebbed away. Apple, plum and cherry trees, all in their fullest blossom grew beside a flowing stream. Within the bower of this delicate grove stood a pavilion made of many colored linens, all patterned with the figure of the white mare. The door of the pavilion had been drawn back to reveal the delicately carved furnishings and rare carpets. On one of these costly couches lay a woman.

"Be welcome, Merlin Ambrosius," she called to him, and her voice was as pure and welcome as water to a man dying of thirst. She was clothed in some fine white cloth that clung to the curves of her body as she rose to stand before him.

"Thank you, my lady." Merlin bowed, feeling strangely clumsy. For a moment, he cursed his wounds that made his movements so stiff and slow. His hand tightened on his staff as he struggled to remember himself.

The lady only smiled and walked forward, holding out both her long, white hands. "Sit and rest," she said, taking his hand in both of hers and drawing him to the couch. "You have come a long way."

"It is a long road yet," he answered. But she only smiled as she turned to the table where a graceful gilded pitcher waited. From it, she poured a wine the color of sunlight into two cups.

"You should drink and refresh yourself." She held out one of the cups.

The scent from the goblet was cool, fresh and sweet. Merlin's mouth watered. He ached, and he knew strength and health lay in that cup. But he only shook his head. "My lady, you know that I cannot."

She raised her dark brows. "You will not," she corrected him regretfully. But she set the cups aside, and instead moved a little closer to him on the couch, close enough that he could tell she was scented like the flowers around them, and that her body was warm as it was fair. "Why not take what is freely offered?"

Merlin found his mouth was dry, and that his pulse beat hard and insistent at the base of his throat. "It is not free, my lady," he made himself say.

She smiled and he could think of nothing else. "Perhaps not. Despite that, I am glad that you have come."

Her eyes were black and deep. Mysteries he would never find anywhere else waited in them. He wanted to touch her hand, and for that moment could not remember why he should not. She would welcome his touch, he was sure of it.

"Why is that?" he heard himself ask.

The lady reached out and touched his cheek. Her hand was warm and soft, and where it moved, his ache eased and her warmth seeped into him. "You are brave, and cunning, true and fair. It has been a long time since such as you have walked the road to me. These days I must roam far and wide to find even a shadow of what you bring."

"You flatter me, my lady."

She laughed a little. "Perhaps." She took her hand from his face, touched her fingertips to his. "Does it displease you to hear yourself spoken well of?"

"It displeases no man." He answered her smile. He could do nothing else. He wanted to prolong the gentle merriment in her black eyes, to hear her musical voice, to have her draw closer.

She did draw closer. The scent of herself was more strengthening than any wine could ever be. "And as I have pleased you, Merlin. Will you please me?" she asked softly. Her eyes were bold. Her warmth ran into his veins, strengthening his blood but turning all his flesh weak as water. "Will you accept what I offer? It would please me greatly were you to do so. There is much I could give to you, not only in this place, but when you return to the living world." She took up his hand between her own. Merlin closed his eyes. There was too much, too much in her face so filled with promise, too much in the warmth of her touch. Too much promise in that and in the words that flowed over him. He was drowning and he had no wish to rise above it.

"My grace would be upon you there, were you to accept my gifts now." She kissed him, and the heat of it rushed through him, burning sense and mind away and leaving only bare need, the need to touch, to know, to take and take again, to revel in the touch and scent and voice of her. It had been so long since a woman had come to him, and he ached with such need now that his arms trembled as he pulled her into his embrace, letting his staff fall to the ground. He answered her kiss hungrily, roughly, delighting in the way she yielded herself so eagerly. There was no pain here, only joy, only heart's wish fulfilled more completely than even dreams could make it.

But as he pulled her closer still, the thorn he had placed in his sleeve drove itself into his arm, piercing the flesh and drawing blood. The small pain found its echo on all the others within him, and in that moment, his head cleared and memory returned to him.

Gently, he pulled away, taking both her hands in his and laying them in her lap.

"I cannot do this," he said hoarsely. "It is not love I seek." Tears threatened behind his eyes as he spoke the words. It was as if winter descended into his heart and would never leave it.

She looked at him, and he saw her eyes were wide and green. "Is it not?" She saw his tears, he knew, but she also saw how he did not move.

"No." He shook his head and dropped his gaze. He could not look at her anymore or he would weep like a babe. If he did that, he might seek his comfort in her, and this time he would not have the strength to leave it. "Nor will it be."

He felt more than saw her draw away. Her shadow fell across him as she stood. Cold. Oh, so cold that shadow. "You have spoken a mighty thing here. Be sure you stand by your words, man, for I will not forget them."

He was suffused with pitiless cold now, and all his pains returned to him. His heart beat heavily in his chest, even as he reclaimed his staff. He stood, making his bow as best he could. He kept his gaze lowered, stealing only the briefest of glances toward the lady. Her face was stern now, all her former delight vanished. She stood aside, and waved her fair hand. The door he had known beyond the blossoming trees opened at once. Merlin walked through.

With each step, his weariness grew. His heart within him beat so heavily, it seemed to be made of lead. He could not see the way forward. It was as if his eyes were still dazzled by the beauty of the lady left behind him. He ground his knuckles into his eyes and groaned aloud. Anger rose up from the depths of his soul. So simple a thing, the need of flesh and heart.

It will not defeat me, he told himself. I will not be lost to such a small thing.

One step at a time he forced himself forward. He staggered in the darkness, and his breath came ragged and rushed from his lungs. But he did not fall, and slowly, painfully, he was able to see another golden light flickering before him.

This new place was far different from the others. No paradise, wild or tamed, waited here. It was only a cavern of damp stone and rough earth and Merlin stumbled as he stepped into it, catching himself with his staff. The light was dim, and the stale air smelled of sea salt and rot. In the cavern's center stood a man. He was tall and well built, with arms and hands hardened by much labor. His skin was seamed and tanned as that of someone who stands out of doors on all days, in all weathers. His hair and beard were dark, but his eyes sparkled brightly.

"God be with you, Merlin Ambrosius," his voice echoed strongly against the close walls

Wearily, Merlin straightened himself, clutching his staff. "What are you?" he asked. His voice was harsh, chilled by the winter still within him.

The one before him cocked his head, and shrugged. "A man, as you are."

Anger flowed sluggishly in Merlin's veins. Anger and impatience. He was tired of games played against his life, and of riddling words and tests and trials. His hands hurt, his feet hurt, his king waited for him and he would be done! "I am in no humor for riddles, sir. Who are you?"

The man smiled. "I have had many names, even as you have."

Merlin leaned heavily on his staff. He hurt. His stomach cramped with hunger, and all his efforts weighed down his shoulders. The anger pulsed in his blood, stronger now, anger for all he had to do and all he must do, anger at this . . . this thing standing in front of him. "Choose one and give it me, or stand aside."

The ghost's eyes twinkled at some silent jest. "My father called me Patricus," he said.

The words fell against him as a wholly unexpected blow, and Merlin stared. "They speak in this land of a Christian man named Patrick."

The man nodded. "So they do."

"What would such a one as you be doing in this realm? Should you not be in Heaven?"

"I am where I am needed," Patrick answered simply. "And I have come to stand before you and ask you to turn aside."

Merlin's cold, pained hands gripped his staff more tightly, and it seemed as if the floor shifted beneath him. He had thought himself well prepared for the tests he would meet here, but this he had no expectation of. This he did not understand. "How can this be?"

But Patrick's face only grew grave at his words. "What you do, Merlin Ambrosius, will cause more harm than good."

Merlin shook his head, unable to believe let alone to understand. "What say you?" he cried like a man gone deaf in his old age. "With this act I will break forever the power of the druid and the magic of the pagan in this land. The followers of Christ will spread and multiply, unimpeded. It was one of your own converts who gave me the knowledge of how to come to this place."

The holy man's bright eyes grew dim and distant. "And in so doing she broke the oath she gave to God. Her repentance will be long, and sore." There was no humor in this, no calm acceptance, only a deep regret. Patrick cocked his head, and in his eyes Merlin saw the last thing he had ever expected to encounter in this realm of the otherworld. Pity. Plain, simple human pity. "You have eyes that see, Merlin," he said. "How is it you are still blind?"

Merlin closed those eyes. They burned. They ached. "I am tired, holy Patrick," he said with exhausted honesty. "I am sick and sore, and have endured much to aid my king, my people and my land. I will not turn aside." Merlin rubbed his brow. He could not stand here. What remained of his strength was draining away as his blood had drained from his wounds. His time was short, terribly short, and yet he could not seem to make himself step forward while this shade stood in his way. "Why thwart me? Why leave this power to the druids?"

He expected another riddle, or a quip, but instead the man spoke simply, and as he spoke Merlin felt a different strength surround him. This strength was greater than mountains. It lifted him up. It willed him to understand and to believe. "Because even in its shadow, God's truth is proclaimed. Because there may yet arise in this land one greater than me who could make the voice beyond speak the glory of Christ." Merlin did not know if he moved, or if the shade of Patrick moved, but they were closer together now. Patrick's voice grew soft, soft as conscience, or hope. "How much would that do, if the voice of wisdom the druids hold proclaimed that greater truth? There would be no more doubt or hesitation. All would be done, and it would be done without jeopardizing the faith in the land of my birth, or in yours. Do not do this thing, Merlin Ambrosius."

Merlin smiled, though he swayed on his feet and clutched his white staff. Without it he would fall, and yet he knew he was triumphant. "You lie, little ghost," he said harshly. "No holy man would speak so. If you were in truth who you claim, you would welcome me to rid your land of the voice beyond."

But the shade before him did not waver, nor did it disperse as he had so deeply hoped it would. Instead, it moved even closer, meeting his eyes. He could not look away, no matter how much he wished to do so. "Ask the question, Merlin, the one that you have not dared to ask. Then you will know why I tell you not to do as you say."

Merlin found he could not breathe. His thoughts swirled inside his skull, battering at each other, clawing and clinging together. Patrick stood before him, patient, hopeful. The sorcerer summoned all the will he had left within him and set the challenge aside. It did not matter. It was no part of his deed. It was as meaningless as the gold and the love that he had been offered. Only his task mattered, only his sworn duty, and that the doing of this great thing was wholly in his hands. That was the only truth. There was nothing else and nothing more. Not now.

One by one, Merlin dragged forth the words he must speak. "Will you prevent me from entering this chamber?"

Now it was Patrick who closed his eyes as if in pain. "I have not that power," he said.

"Then stand aside." Merlin raised his staff, holding it before him like a bar. He felt the power of his art rally within him, flowing with his thick, cold blood. "Stand aside!"

Patrick hung his head, and between one eye blink and the next was gone, silently and simply. Merlin stood alone in the cavern, and the light that had no source began to gutter. As swiftly as he could, Merlin hobbled to the last door and laid his palm upon it. It came open at his touch, and he entered the last chamber.