I was always a slow learner, even though on the day this episode of our story begins I had been practicing Darwinian selection on my brain-cells since just before lunch. More precisely, since just before the lunch that would have happened if we'd had lunch at all—"we" in this instance referring to myself and my two drinking friends of the moment, Steven Speairs and MacParrot.

You know the theory? No? Well, it goes something like this:

Alcohol kills brain cells. Darwinian selection means that only the fittest survive. Give your brain enough alcohol and you are actually enhancing your intelligence because the slow, less fit brain cells are being eliminated.

Some time around midnight you can actually feel this working. You get smarter. We should train our Olympic gymnasts like this. It even worked wonders on my previously nonexistent limbo dancing skills.

But I digress from our tale.

Rule one. Never assume that the big red-haired fellow who is staring cross-eyed at his glass is actually so out of it that he's not listening to the story. Remember this.

Sheila Rowen had come into the pub while I was telling the Wandle Pike Epic to Steven and MacParrot. MacParrot wasn't his real name, of course. He just had a Scots accent so thick that we had to get him really shattered before he'd speak English in a fashion that anyone could understand. Steven called him McParrot, because he always ended up repeating everything three times before we figured out what he was saying. Speairs could call anyone whatever he liked and get away with it, because he had a look in his eye that said "they threw me out of the SAS and then I put on a little weight." That wasn't actually true—the bit about the SAS, that is; the extra weight was there—but when you're that big people tend to assume you're an Honest Man.

Sheila started adding embellishments to the story, and it took a long time. And a large number of pints. It's dry work telling a story like that. It's dry work listening to it too. And MacParrot was in that happy state where he couldn't remember if he'd paid for the last round or not. In the interests of Anglo-Scottish harmony we'd convinced him that it was his shout five or six times in a row.

Sheila's embellishments went on. They were suitable embellishments of course, if a little long. Listen, when someone who cracks walnuts between her forearm and biceps adds them, they're always great embellishments. Especially when the tattoo on her bicep reads All Men Are Mortal and the tattoo on the opposing forearm which shattered said walnuts was a depiction of an Iron Maiden.

Enter the ancient mariner. As usual the place was wall-to-wall with people renting beer, so space was at a premium. I guess the two guys sharing the table with us could hardly help hearing the story with patrons wedged in like that. "It sounds," said the redhead, raising his head briefly from the dead glass he'd been trying to give mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, "as if that pike of yours must be related to the Tinta Falls Catfish. Dexter and I," he jerked a thumb at his mate, "had a run-in with that one."

He had an odd accent, but we didn't think much of it. In South London, you could find someone from anywhere, especially in the Queens Legs on a Saturday Night. Story goes that a few aliens from Betelgeuse used to hang out there. Of course that was quite wrong, but we didn't know it yet.

"Big fish, catfish," said Steven. "Ugly beggars too, with those little tentacly things around their mouths. I heard they got them as big as hundred pounds there." He gestured vaguely, knocking over an empty glass and nearly setting fire to Sheila's hair with his cometlike coffin-nail. He could have been pointing to anywhere from the lower Thames to the Caspian Sea, but definitely vaguely east. "Nothing to a pike though."

"I've never head of the Tinta Falls," said Sheila, "and I was born and bred here."

The redhead looked at his mate. "It's a bit further off and a bit further off and a bit further South. Shall I tell them about it, Dexter?"

Dexter sighed, shook his dreads. "You're going to anyway, Kevin. So long as you don't mention the frigging submersible! I am going to need some anesthetic for this. What are you guys drinking?"

It's the kind of question that Jehovah's Witnesses ought to ask before they ask if you'll listen to them for a few minutes. It guarantees an audience.

"So . . . a fooggin bug fush was it?" said MacParrot, buoyed up by the discovery that it wasn't his round.

"What?

"A fooggin bug fush," said MacParrot slowly.

The redhead then demonstrated he had little survival potential, except for having a mate that was fetching the drinks. "These English accents really get me. Say it slowly?"

We translated before MacParrot could stagger to his feet. "And he's a Scot."

"Oh? So's Dexter. He's from the Makatini clan." The redheaded Kevin seemed to find that funny. "Yep, our catfish are big."

"Nothing to a pike though," said Sheila, jealously guarding the ever pristine reputation of South London.

Kevin took a long look at the tattoo on Sheila's bicep. "Nope," he said. "Not as far as teeth are concerned. But this isn't your European catfish, Silurus glanis, which are reputed to be up to sixteen feet long in the Danube, or your American Channel Cat, Ictalurus punctatus. You get bigger ones in the Mekong and the Amazon—"

"Sixteen feet! And the f . . . ing pudding . . ." I might possibly have said, being in my moment of folly the wedding guest to the ancient mariner.

Red-haired Kevin fixed me with the beady eye. "You doubt me. But I spent eight years at the finest Ichthyological Research Institute in the Southern Hemisphere. Let me introduce myself. Dr Kevin Bagust. I am an ichthyologist—"

"You were an ichthyologist, before the submersible—" said his dreadlocked friend, having returned with the dark amber insurance of a continuing audience.

"Shut up about the bloody submersible!" snapped Kevin, wrinkling his forehead and making his black eyebrows stick out like hairy caterpillars. "They never proved anything, did they?"

"That's because they didn't want the press getting pictures of the tooth marks. And I never mentioned the submersible—"

"Yes, you bloody did. . . ."

As this had the potential for going downhill fast and drying up our new source of drinks, I said, loudly, "About the catfish." I did it in chorus with Steven, MacParrot and Sheila. Great minds thought alike, obviously Darwinianly selected.

It broke through the iron glare-match that was going on between the two. "Ah, the catfish!" said Kevin. "Well, yes. They can be enormous, seriously. Ask Dexter. Let me introduce you. This reprobate is Dexter Guptill. We used to work together."

"Still do," said Dexter, sitting down. "Just nowadays it is on a rig in the North Sea, not on a research boat on the Agulhas banks. And I won't say whose fault it is because I'm not sure that I remember."

It did explain why they had lots of money for drinks. What a couple of riggers were doing in South London was anyone's guess, but they were buying. "So about this sixteen-foot catfish," I said, expecting rich tale.

Kevin shook his head. "Wasn't sixteen feet. That was Silurus glanis, the Wels catfish—"

"Welsh? Called frigging Jones, carrying a leek and singing arias?" said Sheila. It wasn't a Sarf Lunnon fish, and had to be smelled out for yet another Brentford griffin.

"Wels," corrected Kevin. "A river in Germany I think. But that's not the fish I refer to. No, our story is about Clarias gariepinus, the African land-walking catfish."

"And they get on migrant smuggler boats in Tangier and are all working as waiters in the Costa del Sol," scoffed Sheila, "except for the ones that sell kebabs in Bradford."

"Ah've heerd o'thum," said MacParrot. "Ah saw it on the Discovery Channel. They stick their fins oot like this." He pushed his elbows out and waggled his upper torso, and sent my unlit fag for swimming lessons in my beer. "They're no' so big."

Kevin was catching on, or Darwinian selection was improving his hearing because he got it the second time around. "Ah. You seldom see the really big ones go walkabout. They nab the prime habitat, and seldom have to move. They only go walking on land when they have to. They have a modified gill that lets them air-breathe for a considerable time."

"What did you say they were called?" asked Speairs. "Clarias gar . . ."

"It's an unfortunate name. But quite accurate. They'll grip anything. They even snatch washing from women at the rivers." Dexter grimaced. "They're also called sharp-toothed catfish."

"I thought you said they weren't anything like pike," said Sheila. "Changing the story now?"

"They have little teeth," said Kevin. "But damn sharp. And lots of them. Anyway, you want to hear the story or not?"

"Mark my words, it is another man-eating swine from the Fleet ditch story," said Sheila.

"Oh, they eat men," said Kevin. "But mostly they wait till they're dead. They're like eels. Fond of murky water and food that is good and ripe. Slimy buggers just like eels, too. Got this big wide mouth on them. They'll swallow anything up to a third of their own length, whole."

"A third of sixteen feet . . ." It was unfortunate that Darwinian selection also seemed to work on numbers. The things got stronger as the evening wore on.

"No," said Kevin. "These ones don't get sixteen feet."

His friend shrugged, sending the dreads bouncing. "We don't think, anyway. The angling record is ninety-seven kilograms."

"What's that in pounds?" I asked. "About fifty? That's a fair size fish."

"Nah, it's the other way around. You multiply by 2.25," said Steven.

There was the silence of alcohol-fuelled heavy cogitation. "That's something like two hundred and twenty pounds. Damn near as big as the pike. . . ." mumbled Sheila, impressed despite herself.

"A lot bigger than the official record for pike," I said, risking life and limb.

"Yeah, but getting the real big ones out of the water . . . I mean look at the Wandle Pike," said Sheila.

"Well, these are tough conditions to get a fish out of," said Kevin. "They like to hang out in old tree-roots and in rocks and garbage on the bottom. They know every trick in the book and then some to break you off. Anyway they're bottom-feeders, and the big ones never leave their lairs. They pick places where the river brings them their food—not easy places to fish. Anyway that is the official record, but I've seen one that made that look like a tiddler. Hundred and fifty kilos if it was an ounce, what was left of it."

"And you caught it," said Sheila. "But a bigger one bit it in half . . . Pull the other one."

"No, it was found on the beach at Manz'Ngewenya pan. The crocodiles had eaten the other half. We had to guess," said Kevin.

Now that was a conversation stopper, especially as he said it with a deadpan expression that would have got a drug-crazed rapper off the hook, even if the cops had caught a stash in hand.

"You used to go fishing with crocodiles?" asked Steven, after a good minute's silence.

"Nah, we usually used worms. His girlfriend had them," said Dexter, looking at the glass in his hand. "Terrible evaporation problem you guys have with this beer of yours."

Now we were back on familiar territory. We could swap lies and insults about the women who disdained us with the best of them, although you had to watch outright slander with Sheila around. She was good value in most ways though, and was an education in the department of coarse invective. "It's your round," said Steven cheerfully. "And in exchange I can tell you about a wench I once knew who was into crocodile wrestling."

"Given a fair choice of wrestling you or the crocodile," said Sheila, looking at him, "I can't blame her for choosing the crocodile. Anyway, it's your round."

"I'll pay for it," said Kevin, shocking us all rigid, "If someone else goes and gets it. If I stand up I'm going to fall down. It's a terrible childhood problem I have to live with."

"Which only affects you when you're Vrot. Plastered," said Dexter sarcastically. "Which you're only about half. Get up, you lazy swine."

He did, and proved, a little later, that he had a retentive memory as well as childhood problems. "About the catfish . . ."

"Which was sixteen feet long and was walking for the bus, when you caught it with a crocodile," I said.

"Look, do you want to hear the story?" the ancient mariner asked, pushing beers through the slop on the table.

I took the pint glass. "When you put it like that I do."

"Ah've always had grea' untrest un Africa," said MacParrot owlishly, taking his beer. "Pagodas and wee wee dancers wi'long fingernails and tinkly music, and bein' able to smoke a cigarette or shoot a ping-ball with their watchama . . ."

"That's Bangkok, you Scots prat," said Steven.

MacParrot blinked in surprise. "Usn't Tha' un Africa?"

Kevin fixed him with his beady eye. "Geography is not something that they teach you English much of."

It took us a while to get back around to the catfish but we did, with a sort of piscine inevitibility. Well, they do rule the universe. "Imagine, if you can, a dirt road which goes into the bum end of Africa, if not the universe," said Kevin. "The veldt is as barren as a politician conscience. There is nothing there but little thorn bushes and dead grass. Two hours off the freeway, and I reckoned all they'd find was our tire tracks and two dry corpses sitting in the truck."

He jerked his thumb at his companion. "He didn't help because he kept looking at the map and saying things like 'we should have gone right at that windmill' and 'we're bloody lost, aren't we?' Ha. This from a man who had doomed civilization as we knew it by leaving the beer cooler behind."

"It was an accident!" protested Dexter.

"Mark my words, everything that happened on that fateful day can be blamed on that incident," said the ancient mariner.

Dexter attempted to defend what any lawyer in creation could see was the indefensible. "The beer was warm. I shoved it and the cooler into the chest freezer to cool it all as much as possible. You said that it was a good idea."

Kevin gave this excuse the disdain we all knew it deserved. "Don't trouble me with logic and excuses. All it meant was that by the time we arrived at our destination we were both too dry to be sensible about drinking. Anyway, despite Dexter's lack of faith and his folly with the beer—God, I'm thirsty even thinking about it—we came over the ridge and there it was. The Lucacha River. A little strip of greenery with yellow fever trees and one helluva big mango orchard. It was the bloke that owned the orchard that was our reason for going off into the arse end of nowhere. Gerhardus Van der Plank. He'd decided that he had a river, and as the bum was falling out of the export fruit market, that he'd build himself a fish-farm. He exported fruit and he'd been to the 'States on a marketing trip, and he'd eaten catfish at a restaurant. When he figured out that it was what we called 'baarber' he got a bee in his bonnet and decided that he could make a fortune exporting fish to the U.S.

"Now, Clarias looks similar to Ictalurus. They both have barbels around their mouths and they're both scale-less. But that's where it ends. Clarias air-breathes, likes water that's indistinguishable from muligatawny soup, you know, warm and full of curry and things you better not think too much about. It's nothing like Ictalurus in texture. Clarias is tough and doesn't flake, and it tastes of mud unless you keep in clean, running water, without food, for three days. But Van der Plank was willing to pay us to consult on breeding Clarias, and we were broke. So there we were on a Sunday, moonlighting, in the middle of nowhere, and as dry as dust gods, with a truck full of everything essential to get Clarias to spawn, but no beer."

"Van der Plank had that," said Dexter. "And once he got over the fact that his consultants weren't both lily-white, he was very generous with it. His wife was away in town and he was catching up on his drinking while he had the chance."

"Anyway we looked over the place, had a few beers, said polite things, not like 'you've got more money than sense,' had a few more beers, and got things set up in his hatchery building. We had a few more beers while we were setting up the egg-screens. I guess Van der Plank didn't get too many visitors, in the arse end of nowhere. And it was bloody hot. And dry." He looked pointedly at his glass. "Like that," he said. And all unbidden (well, undragged, and without someone having an armlock on her) Sheila went to get us another round. It was a dangerous sign.

"Now, by this stage we getting quite inspired by the idea of selling South African catfish to the Americans. Clarias have real advantages over a lot of other aquaculture species. The water doesn't have to be clean and oxygenated and they'll eat damn near anything. And you can take them out of the pond and six hours later they're still alive, and will swim off if you put them back in the water. So Dexter here says "well, let's get your brood fish and give them their pituitary extract injection," to Van der Plank."

"What? Inject them with what?" asked Steven.

"Pituitrin," said Kevin, as if that explained everything. "It's like heroin but different. It's made from fish pituitary glands."

"It's a date-rape drug for fish," explained Dexter.

"And the pudding," I said. "I suppose there's a big market for it with fish shaggers—"

"No, really!"said Dexter, hurt by my doubts. Well, trying to look as if he was. He didn't have the face for it. "Catfish only spawn when they get the environmental triggers. The summer flood. As soon as the water gets warm and muddy they release hormones from the pituitary gland, the eggs swell overnight and they're ready to spawn. We just cut out the middleman or the flood."

"And this is where the mad scientists accidentally inject the fish with radioactive isotopes and instead breed super land catfish that are out to conquer the world!" said Sheila.

"Well, I met one on the tube yesterday," I admitted. "So what did you beggars do to these poor fish, pissed as newts as you undoubtably were."

"Nothing. And we weren't pissed yet. Just slightly cheerful. The newts part came later," admitted Dexter.

"What do you mean nothing? Did you inject his wife by accident?" I asked.

Kevin snorted. "I did that once. Well, I injected the guy who was supposed to be holding the fish still. He was convinced that his nuts were going to drop off."

"And did they?" asked Sheila.

"I never looked," said Kevin. "But his wife had twins nine months later, so either it worked in some other way, or she called in consultants to help out. Anyway this time it was that Van der Plank had collected some fish from the river but they were all too weeny. If you want quality eggs you've got get yourself some quality brood fish. Big females. The bigger the female the better the quality of the eggs."

"I told you so," said Sheila, nodding.

"Yeah, and they have more eggs and the size increases slightly too, which means better survival to swim-up. Anyway, Van der Plank only had little fish. Too small."

"Besides you'd have been ashamed of yourselves injecting that stuff into little fish."

"We should have stuck with them, but we'd got a bit inspired. We'd run out of beer and that's when things really went wrong, because Van der Plank turned out to be the local mampoer king. It's a sort of white-lighting he distilled from fruit. A very little bit of that stuff and you think that you're superman. A little more and you don't think at all. We decided to go down to the river to catch a really big mama. No messing around now, we were going to catch something that would give him a million eggs. Well, Van der Plank went looking for some tackle and left us to admire the quality of that mampoer, while he went into that house of his. It was one of those 'spogpaleis' places, you know, a got-rich-and-have-to-show-it thatched monstrosity, with white fluffy carpets, not for scruffy fisheries consultants. So we sat and kept the mampoer company. The stuff was like drinking barbed wire, but you got used to it after a while. He came back with a surf rod—one of those real old telephone poles from the very early days of fiberglass rods, solid enough to hammer into the ground as a mooring post, and strong enough to pole a cruise liner—with a twelve-inch Scarborough reel and a rusty 13/0 shark hook, and, I kid you not, a whole chicken. I might have said something about us needing a decent size bait for a decent size fish, and Van der Plank wanted the biggest and the best for his new venture. By that stage we wanted it for him too. The chicken was going to be lunch. We should have eaten it, but this was a holier purpose.

"Well . . . the river. I don't know if you ever read the Kipling story about the Elephant's child? About the grey-green greasy Limpopo River, all set about with fever trees? Well, this was like that, but smaller. I must have had at least one grey cell still functioning because I took a long look and said 'and what about crocs?' to our genial employer."

"And that was the last grey cell that functioned all day," said Dexter. "'Cause Van der Plank said they'd all been shot out and we had a drink to celebrate. I mean, I'm all for biodiversity and all that, but not when I have to work in the water with the damned things."

He shuddered. "So we did a kind of walking fall along the river bank looking for a good-sized hole to fish in. But the reason Van der Plank had little fish was pretty obvious—it was too shallow and too fast moving for a good big catfish habitat. Anyway, we found the best we could and sat down under a wild fig with the bottle and our new mate. He was telling us, lamenting really, that we couldn't go and fish in the Tinta Falls pool just off the bottom of his property. As a kid he'd caught catfish, big ones, in the waterfall pool. It's just the kind of place they like. The farm the pool was on had been bought by some rich city type who had put in game fencing—electric fences yet, 'cause he had buffalo, and then he'd fought with the locals. Accused them of poaching."

"Utterly impossible of course," said Kevin, sniggering.

Dexter coughed unconvincingly. "Never! Anyway, it was hot, and there was nothing much happening, and the flies were pretty bad . . . and our new buddy said that he was going back to the house to sleep it off before his wife and daughter got home. We stayed for a while. If it hadn't been for the flies we'd probably have stayed longer. But they were excessively persistent. Like tax-collectors. So we decided to move."

"Yes, it was all the flies' fault," said Kevin, with all the facility of a man whose fault it never is. "And the rest of the bottle. We should have left the bottle. But that part was all Dexter's fault. He'd evolved this new fly-killing method. It involved taking a sip of the stuff and then trying to breathe out on a fly."

"They withered. Or at least fell out of the sky," said Dexter. "It seemed like a good game at the time. You said we had to keep it secret from the Australians or they'd steal it and get better at it than we were."

"Well, it's true enough. I won't bother you with the rules we worked out for drop goals and converting a fly instead of a try. Just in case there is an Australian listening in. They have stronger bladders than we do."

"Ut sounds a fine game," said MacParrot. "Wud it worrrk on midges?"

Dexter shook his head. "I'm not sure it even worked on the flies, although Kevin claimed several tries, penalty points, and a conversion. But between that game and the fishing rod, we were doomed. We took the rod along with us. We shouldn't have. Somehow we found ourselves at the top of the falls at the lower edge of Van der Plank's property."

"Now I'd like to tell you that Vic Falls has nothing on the Tinta, but I'd be a liar if did that," said Kevin, righteously. "It's about five hundred feet high—"

"Make that fifty," said Dexter.

Kevin glared at him.

"Meters I mean," said Dexter.

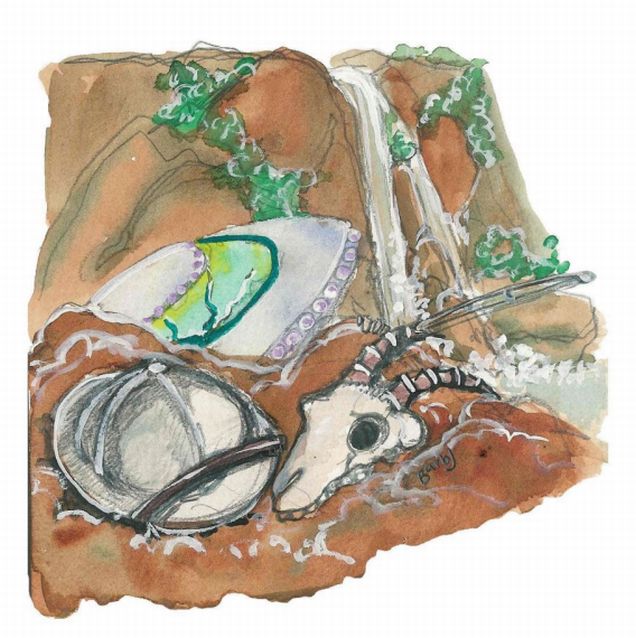

"Sheer red dolerite, stained with white streaks of ibis shit. And down below it is this pool, in among the boulders. Deep, dirty-green water, with a few bits of dead tree sticking out of it. The perfect place for big Clarias."

"All fenced in by a twelve-foot electrified game fence," added Dexter.

"Now, sober and sensible we would have looked at that fence and said 'whatever this guy has inside that kind of fence, we don't want to meet it, not on foot.' Instead, we took it as a challenge. He was trying to keep us out. Stop us catching the mama-catfish to end all mama-catfish. Bastard! He just had no idea of the caliber of men he was dealing with, or just how completely blotto we were. The fence met the rocks at the end of the cliff that the waterfall went over, and stopped. I guess it was just too hard to fence further, and it would have taken a fairly athletic member of the big five to climb out."

"Too much for a leopard, but a piece of piss for two fish-crazed drunks and a fourteen foot surf rod," said Dexter, raising his eyes to heaven.

"Yeah," agreed Kevin. "So we had a good look at the end bit of the cliff and decided we had a real problem."

"The cliff?" I asked.

Kevin shook his head sadly at the lack of Darwinian progress in my skull. "What's a mere cliff? No, this was serious. The bottle of what was left of the mampoer. We couldn't risk carrying the bottle on such a perilous journey."

"So you had to drink the rest of it." I said, understanding dawning. There was a certain logic to this, after all. The kind of logic all of us at that table understood perfectly.

Kevin nodded. "Indeed. And it had got very smooth by that time. It was amazing how much lower it made the cliff seem. And to tell the truth it was only about sixteen or seventeen feet high. You could reach down with the fishing rod."

Dexter started laughing. "He did. Only he lost his balance, and there he was clinging to the end of a bending fishing pole, yelling for me to haul him back."

"Who is telling this story?" asked Kevin.

"We are," said Dexter, taking a pull of his pint. "You leave out the good bits if I let you do it alone."

"Did you rescue him?" asked Steven. Dexter was a small wiry man, whereas Kevin was red-haired and chunky.

"I tried," said Dexter, "but it was a mistake. We both went over and did a sort of half-assed fishing-rod pole-vault into some thick scrubby bushes. I had a soft landing. I landed on his head."

Kevin sniffed and continued. "So we were down, alive and not even too badly hurt. And there was a gully to follow down to the waterfall, and we had a rod. We were ichthyologists, dammit, off to fish the unknown and to collect bloodworms where no man had collected bloodworms before. Or at least not while a conservation official had been watching. Forward into the unknown, and down the scree-slope. How we got to the bottom of it without breaking our necks and the fishing rod, I will never know. We passed the mummified bodies of dead explorers in pith helmets and the wreck of a small Martian space-ship with rod-racks. . . ."

"He is prone to exaggerate a little, but there was an old rusty dead Chevy with those big wing-mudguards from before the war and also the bones of a goat," said Dexter. "It really was not the easiest slope I've fallen down, even stone cold sober. It must have taken us about half an hour to get to the pool. The water polishes that red-weathered rock to glassy black and I have to admit that it was the sort of place that you'd have expected a horned green thing with a pitchfork to come out of a dark cave and charge you entry fees. It was hot enough, and the air was thick and still. The water lapped at the edge of black rocks before it slid away down polished channels. Nets of long filamentous algae swayed in the current. And then Kevin lets out a loud rebel yell that echoes off the cliff, just great for your secretive poacher, and shouts yeah baby, let's fish! at the top of his quiet little voice. He's a real boon to stealth, is Kevin, but other than maybe Beelzebub junior peering from his cave, I didn't think there was anyone to hear him. He picked a nice high rock to stand on, and started to get the rod ready. I was happy to let him because I'm from the Cape. We don't use Scarborough reels, and they take some getting used to."

Now Kevin broke in. "A quick digression about the Scarborough reel. I don't know if anyone outside of South Africa still uses them, but they're a simple center-pin reel with bearings. It's kind of too-basic-to-go-wrong technology. It's also something that looks ridiculously easy to use in the hands of a pro, and a complete circus in the hands of a tyro. Casting with a Scarborough reel involves something that looks a little like a pirouette. Anywhere along the Zululand coast when the shad are running—shad are what you guys call blue-fish—you'll find a mob of Indian fishermen doing little ballet dance numbers and yelling 'Coming ho-vah!' as they fling old spark plugs—they're cheaper than sinkers—into the sea. When you hear that cry you make like you're a tortoise, because a low-flying spark plug can ruin your hairstyle. In the hands of a real pro they can throw as far as a man with a Penn."

"Well, we didn't have to throw that far as this pool was only about forty meters wide. This was a good thing because I knew that Kevin was not half as good with a Scarborough as he liked to pretend he was."

"A vile slander," protested Kevin loftily.

Dexter snorted. "Yes, so vile that when I heard you say 'coming over,' I dived flat. I didn't care what was in front of me, and I should have, because it was the edge of the bloody river. I looked up from the water and there was Kevin doing the mightiest Scarborough reel pirouette I've ever seen. Only halfway through he lost his balance, sat down hard, and the reel hit his stomach . . . And it stopped spinning."

Dexter took a mouthful of beer. "Now work out for yourself what happens when you put a four-pound chicken on the end of a fourteen-foot lever, then add a lot of acceleration to it . . . and just when it has really built up momentum . . . stop it dead. The hook dropped into the water about fifteen feet away from him."

Kevin shook his head ruefully. "I blame the demon drink myself. The hook stopped. But the bait-chicken didn't. It hit the cliff wall about fifty feet up with a solid splat and bounced back and landed in the water. It must have had some air trapped in the body cavity, because it floated. Bob, bob on far side of the pool next to the waterfall."

Dexter took over the tale. "I hadn't even sat up properly when it happened. You know, there should be that 'doom doom' music at this point, but we both saw it. I'm not kidding you, it was like the thing from the black lagoon. It came soooo slowly. All we saw was the mouth, barbels like black ropy tentacles spreading across the water, and then it sucked that chicken in, with a 'schloop' noise you could hear even above the waterfall. The mouth must have been . . . well I swear there was guy inside there looking for his Harley Davidson. This was no mortal fish. No, this was the offspring of Cthulhu himself, who had sneaked through some dark portal into this world for a quick chicken dinner. A thing of fear and trepidation swum up from some nether region. This was the Loch Ness monster's long lost cousin."

"If you show two ichthyologists the peril from the deep . . . there can be but one reaction," whispered Kevin earnestly.

Dexter nodded. "Indeed. We just had to catch it."

"Not a matter of choice, a matter of stern duty!" Kevin raised his glass in a salute as his companion continued.

"I got out of the water and took all my clothes off, and spread them out on the black water-polished rocks to dry. Man, we were in the middle of nowhere. There was no one to see me, except bloody Kevin, and we'd shared a cabin on enough research vessels for me know that I could bend over with perfect safety. And it was a hundred and ten degrees in the shade. I suppose could have kept them on and they would have dried on me in ten minutes. But I wasn't being as logical as I could be, not after seeing that fish. Meanwhile, Kevin had the full-steam mutters. 'Why the hell did we come down here with no bait?' and cursing and swearing much better. He'd taken off his shirt—it was hot work and he was turning over rocks looking for frogs or crabs or something we could use for bait. I went down to join him, me without a stitch on. Like, we're both on the far side of not sober, but that fish—well, it cut through alcohol like an ice bath.

"And then I heard a little 'clack-clack' on the rocks. It was the handles of the Scarborough reel, turning ever so slowly as something pulls out line."

"I got to it before him," said Kevin, taking over. "Struck as hard as I could. There must have been a fragment of chicken left on the hook."

"Or maybe it was just willing to swallow any foreign object that might possibly be edible. They caught a Zambezi shark with a full tin can in its stomach once. Anyway, Kevin was in. The fish took off like a steam train. It even bent that telephone-pole of a rod that we were using. And then we had an epic battle of man against the monster of the deep."

"I was sure from the start that it wasn't the real monster, but I thought a fish fillet would be perfect bait for the Leviathan of Tinta Falls, never mind the fact that we didn't even have a penknife with us. I had the advantage of a heavy rod and line like cable. Oh, the fish tried to break me off on trees, but there I was, standing on the dark rock, lifting him off the bottom. It was a good size fish, one I'd have been delighted to catch on any other day of the week—but that day I had seen the holy grail of catfish fishing. That day it was just a fish. I called to Dexter to come and help me land it."

"So there I was," said Dexter, "still as undressed as a man could be, and I rushed into the shallows to grab the fish. This is not IGFA rules stuff, Kevin had tackle you could subdue a five hundred pound shark with, and we were going to need it, if ever we got to the monster fish. Now, as I said the rocks down there were polished as smooth as slime-covered glass. It was a big fish. As I reached down for the fish and grabbed that lower jaw, my feet betrayed me. I had a grip, but I'm on my butt in the water, half covered in a fish that was damn near as big as me, and as slimy as hell and mad too. And then I figure that I am not alone in this bit of water, and I am not just talking about the catfish I am wrestling with. Obviously there are a lot of catfish in this pool, but they won't dare to go into the deeper water, because there is nothing big catfish like to eat as much as little catfish. With all this splashing going on they all come to see what it is about, and if there might be some scraps to eat. All of the little ones whipped themselves into a feeding frenzy. The were gripping onto anything they could find. They have tiny little teeth, but they're grabbing everything. And Kevin is yelling that the hook has come out and I must for God's sake not let go."

"He was rolling around, trying to stand up, falling over, and the water was boiling around him," said Kevin. "And out in the deeper water I saw that big dark shape rising. Obviously the commotion was attracting it. Maybe it figured that Dexter was an injured animal or something."

"I was, dammit!"

"Now I was not going to let the monster catfish take my buddy, not without at least getting him to hold the hook while he was being swallowed," said Kevin. "So I jumped down there. Which turned out to be the luckiest decision I have ever made, because someone on the ridge, the owner or one of his game guards, started shooting at us."

"Oh come on! Not likely," I said, as if the rest of the ancient mariner's story had been. "For what reason? For trespassing? Come on. Tell us another one."

"Poaching," explained Kevin. "This is in a country where poachers use AKs, and shoot first. This isn't Fred from the village just nicking a few grouse or bit of venison from some bloated landowner. It is high value organized crime. Poachers are after rhino-horn or ivory and it is shoot-first-ask-questions-later stuff. If we hadn't been so totally bladdered we wouldn't have dreamed of doing what we were doing."

"The weirdest thing about the whole scene," said Dexter, "was that before those shots I was wrestling with the catfish. And just after it happened the fish went limp. I don't think anything hit the fish, but maybe in my shock I'd smashed it against a rock or something. Catfish are nearly impossible to kill, but you can stun them."

Kevin nodded. "We kind of both stopped thinking at that point. Well, if we'd been thinking we wouldn't have been there. As it was we just ran."

"Ran—lugging that fish between us," said Dexter shaking his head. "I don't know why we didn't drop it but . . . well let's be honest, we weren't being too logical. I blame that mampoer. And the adrenaline. If I'd been thinking at all I would have dropped the fish and grabbed my pants. But as it was we were deep in the trees about five hundred yards from the waterfall before I ran out of breath. There we were, on the run, shaking, scared—and me with nothing but a fish to wear. The bastard on the ridge had lost sight of us. . . . Actually, he probably hadn't intended to hit us, just to frighten the shit out of us, in which he had succeeded admirably. He was still loosing off a few random shots so there was no way I was going back for my clothes. Near the river the bush was thick. Thorny as hell of course, but we were fairly safe unless they came down there looking for us, which I figured they probably would do, but it would take them a while to get there."

"We decided to follow a run-off gulley away from the valley. When they came to look for us, we didn't want to be there any more. It was unsociable, but I have found I get like that when people are shooting at me. It was, like most of the decisions we'd taken that day, superficially sensible."

Dexter snorted. "Depending on your definition of sense or if you were not wearing trousers while trying to carry a large floppy slimy fish up a valley full of haak en steek thorns, jiggyjolas—what you'd call brambles—and nettles. I know nettles. I'm a lousy botanist but I'll never forget them after being caught short on a field-trip and thinking those furry leaves would make a great substitute for the 'loo paper I didn't have. I remember those leaves well. I have reason to never forget them."

He winced at the memory, before continuing. "I still clung to that fish. I'd lost my clothes, damn near my life, the big one had got away and all we had to show for it was this fish. At least it was ten times the size of the fish in the brood stock pond. Actually by the weight of it it might well have been a record. And it was all I had to wear. We hadn't heard the sound of shots for some time, and so we decided to get out of the impenetrable undergrowth and risk slightly more open ground. And then Kevin froze. I nearly rammed a catfish spine into his back. I started to swear—"

"Did swear," said Kevin, trying to look deeply shocked, and also failing at that.

"And then I shut up. Because just above the Grewia bush was a pair of horns. All we could see were the tips. I'm not kidding. They were at least two yards from tip to tip. We're fish people, not big game zoologists. But even we knew that big solitary buffalo are the worst and the most dangerous kind of buffalo. This one must be enormous with horns that size . . . and I hoped like hell that it was solitary. It could only run after one of us, and I hoped it would be Kevin. If only that had been a loaded catfish."

"We'd still have been standing there to this day," explained Kevin, "Frozen like a pair of statues holding a fish, if the right hand horn hadn't moved off . . . Showing us a different left-hand horn . . . and the face of a wildebeest. What you'd call a gnu. Two complete large mammal ignoramuses us, we couldn't even tell the difference."

"They don't have fins," said Dexter, dismissively.

Kevin nodded in agreement. "And everyone—even us—knows that a gnu is quite the nicest creature in the zoo. But that was enough for us. We had figured out, finally, that being here was as dumb as rocks, and if we didn't get shot we might just get taken out by the wildlife. We made a beeline for the fence—"

"Which was when we saw the error of our ways," said Dexter. "The reason the dangerous wild animals were in and not roaming Van der Plank's orchards: the twelve-foot electric fence. Now I don't know if you English people are familiar with the electric stock fence. It's got a pulsed charge, high volts, low amps, shouldn't kill you unless you have a heart condition, but not the sort of thing you'd want to touch twice, let alone try and climb through. Mostly the fences have low strands a few inches apart, and the spaces get wider as the fence gets higher. At waist high, they're about six inches apart. Not easy to get through. Still, about five yards from the fence was the dirt road, safety, and a way back to our vehicle and some clothes. So we got clever. We collected a bunch of dry dead branches, and by wedging one in the chest-high wire, and raising it a few inches we could then raise the next one down a few more inches with the next piece of branch, and so on. They were old, rotten termite-eaten branches and it took us a while, but we rigged a gap that a man could step through cautiously. Kevin tried it out and he got through fine. Then it was my turn. I didn't have any undercarriage protection, so I was being very cautious. I didn't want any dangly bits having a shocking experience. What I hadn't figured on was the fact that I had this big floppy fish with me. I was halfway through and I asked Kevin to come and take the fish—which he did, reaching through the fence. But the tail touched the wire as he took it. It made slimy, wet, good contact."

Kevin raised his eyes to heaven. "And then we had a divine moment. We had a fish resurrection. The fish I was holding went from limp to thrashing like a mad thing. I was getting shocked every time it touched the wire, and every time it touched the wire it did an imitation grand-mal epileptic seizure and tried some air-swimming—lashing that tail around and making more contact with the fence. In this thrashing process it slapped Dexter and he forgot he was straddling an electric fence and he stood up, and grabbing the fish. The dead branch construct collapses and three of us—the fish, Dexter and me are doing a St Vitus' dance with the fence."

"Somehow we ended up, all three of us, on the right side of the fence, sitting in the middle of a dusty road, under the threshing fish. A fish that wanted desperately to return to the fishy waters of its birth and get away from these lunatics."

"And then," said Kevin, "barreling along the road comes a taxi. Now this is not one of your civilized black cabs that will just overcharge you and bore you to tears with their charmingly informative conversation. This is not even an after midnight minicab driven by a kat-chewing Somali refugee. This, my friends, is a South African taxi. It's a minibus, officially designated to hold fifteen people. When two of them crashed in Maritz street they hospitalized forty-seven, and at least ten passengers just walked away. The vehicles are the last word in racing heavy-duty off-road 4X4 go-anywhere cars, only topped by the company car. They have four bald tires, more pirated and stolen parts than Blackbeard, they're held together with fence-wire and spit, and they are all driven by future world champion rally drivers, if they live through the next ten seconds. Oh, and the drivers are all armed to the teeth in case of deadly danger, like another taxi stealing their fare. Taxi war shoot-outs are a regular feature of South African newspaper stories. If you see one of these vehicles, run away. Well, run, if you're not sitting in the middle of the road in a shocked and dazed state under a squirming slimy catfish, that is. We just, all three of us, managed to roll to the edge of the road and get left in a cloud of choking dust. And then the vehicle skidded and swerved to a halt. We thought we had a lift, and I was just standing up saying to Dexter that maybe we should rather walk, anyway . . . when the occupants of the taxi fell out of the door."

He grinned at the dreadlocked Dexter, who was looking at the ceiling. "There was Dexter dressed in his best fish . . . and there were at least twenty elderly to middle-aged large Zulu mamas in their blue and white Apostolic Zionist church finery—which is a special uniform outfit that makes sure no one can see anything indecent like an ankle. They all had these big blue and white golf umbrellas. They took a long look at the prince of modesty and they charged in, swinging their umbrellas, ululating and yelling at the nudist pervert. I behaved like a true drinking friend and sat on the edge of the road and watched him try to hold a fish over his head, his little buttocks twinkling in the sun as he ran from a mob of rampaging blue behemoths. I laughed until I thought I'd die.

"He took shelter in a culvert pipe that went under the road. They didn't want to get their finery dirty, but they took turns for a good ten minutes at trying to poke him out with their umbrellas."

Dexter shook his head. "There I was at the mercy of the mob, lying in a pipe which had been half filled with mud, with about two inches of clearance above my head, if I held it sideways, in about an inch of glutinous frog-filled water, clinging to a now water-revived catfish, with umbrella ferrules poking at my feet. It was not a happy place to be, I promise you. Anyway, a little later Kevin came along and told me they'd gone. And so had the damned catfish. Now I was not, at this stage, about to give up on that fish. Not after what we'd been through. It was going to be injected with pituitrin before nightfall! So I leopard-crawl squirm after it. Down this end the pipe was about three quarters mud, and I couldn't quite get a grip on its slimy tail. So I yelled to Kevin to come and grab it at the other end of the pipe. And then something squirmed past me and over my foot—not the catfish because I was touching the bloody thing's tail. It's a snake, I figure. I don't know, it might just as easily have been a leguvaan, a monitor lizard, but I have a thing about snakes. I wasn't going to stay in that pipe, and I wasn't out going backwards either."

Kevin's shoulders shook. "The pipe just about erupted. One moment, there I was standing in the ditch and the catfish head was sticking out of this half-pipe full of mud, and I was just getting a grip on it, and the next moment there was this scream fit for Halloween Three and Dexter came out of there like a champagne cork in a shower of yellow mud. He was gibbering like mad and he clung onto to me like a sailor does to his wife after three months at sea. And then we looked up and realized that this big white Mercedes had quietly driven up and two blond beautifully coiffured women were sitting there staring at us with their mouths open.

"We all looked at each other in one of those frozen long, long moments, and then before I could say anything, or Dexter could cover his dignity with a fish, the driver wound down her window, and a flood of expensive scent and air-conditioned air came washing out over us. In a voice that could be used to counter global warming the woman says 'Sies!' In case you couldn't guess that means 'sis!' but in Afrikaans, which has a lot more feeling than you can cram into English. 'What do you think you are doing?' she asks. The make-up on her face was plastered on as thick as the clayey-mud was on us, but it was possibly more carefully applied. It was cracking at the edges from her sucking lemons expression.

"Now, there I was, standing in a ditch next to a rural public road clutching a five foot struggling fish, covered in mud, with a naked man clinging onto me. What sort of answer did she think she'd get? I didn't like her tone. It offended my mampoer impaired dignity. So I said 'Darling, what does it look like? But now that you're here, get your kit off and join us. Dexter can have you two. I think I'd rather go on having it off with the fish.'"

He took a pull of his beer and jerked his thumb at his partner in crime. "Dexter blew her a kiss and she did a damned good imitation of a catfish."

"I didn't think anyone's mouth could go that wide. We gave her a fine one fingered salute," said Dexter, "while the two of them gaped at us."

Kevin nodded. "It must have taken her a good minute to find her wits. Then she screamed: 'I'm going to find my husband to come and have you arrested!' And she floored it and left us in the dust."

"We took cover after that," said Dexter. "If we even thought we heard a car, but we only had about half a mile to walk to the farm gate. And then we knew we were home free, as it was Sunday and only our friend Van der Plank was around. We were starting to feel quite triumphant. We had overcome! So, instead of putting the fish into the hatchery and digging out some clothes, which is what I had thought was a good idea, we walked up to Van der Plank's thatched gin-palace and pounded on the door, proudly holding the fish between us like a very muddy, slimy medal of honor."

Kevin smiled reminiscently. "The door opened and we spilled into the white flokati carpets out of the bright sunlight dazzle . . . and the two elegantly dressed women from the Merc started screaming at us in chorus. That's when we dropped the fish. Onto its back. It flipped over, and, as if it was returning to primal waterweed, it set off with a slime, mud and blood trail across that white fluffy carpet, straight for Van der Plank's wife and daughter."

"Being real he-men we turned and ran like hell," said Dexter. "We got into the truck and got out of there as fast as it would carry us. Didn't stop until we were just off the freeway, when I got into some trousers, before, as our luck would have had it, we got stopped by a traffic policeman."

Kevin threw up his hands. "There was nothing else we could have done anyway. 'Cause when we dropped the fish onto its back we realized that he would pretty useless as a mama-brood-fish."

Dexter nodded. "We really should have checked the sex of that fish a little earlier."

"An amazin' tale," said MacParrot. "Och, the part aboot the catfish bein' related to the Loch Ness monster. Happen I've some pictures—"

"Last orders please!" shouted the barman.

In twenty minutes we'd be out in the cold night air of South London. We needed fortification against that. Or so we thought anyway. When I got to the bar the barmaid leaned over and pointed to a chubby little fellow resting in the corner. "The man wants a word. About fishing, he said."

It would seem that mine host, the owner of the pub, had long ears. Closing time meant closing time unless you were invited to stay after the doors are locked. In which case it is a private party, at least in beady eye of the law . . . It's a fiction you can get away with sometimes. It turned out that Kevin and Dexter had not been the only ones listening in to the tales of others, and that mine host was part of brotherhood of the angle.

There is always an angle, especially at about one- thirty in the morning after a large number of pints. And the ancient mariner's crew had shed his catfish, but mariner himself still wore the tooth-scarred submersible about his neck.

Of course, the tooth-scars on the submersible are nothing compared to what the Loch Ness Monster could have done to it. But that is another tale, along with our encounters with that secretive organization, the Brotherhood of the Angle. The story of lock-in and the great Loch Ness fishing expedition is not one lightly embarked on. That's for our next episode.

Eric Flint is the author of many novels and some short fiction. He has also edited a number of anthologies. Dave Freer has written a number of novels and short stories. Andrew Dennis has co-authored books with eric flint. This is the first time the three have worked together.

To read more work by these authors, visit the Baen Free Library at: http://www.baen.com/library/