Written by Jason Wittman

Illustrated by KarlA. Nordman

When I first met Molly Flammare, I hadn't heard any of the stories they told about her. She was definitely a dame to tell stories about—later, when it was all over, I heard any number of them told in darkened bars, or around barrel drum fires, by men with nothing better to do than sit with their buddies, or their shot glasses, and spin their dreams—though, when Molly was the subject, the dreams often turned into nightmares. But I was new in Minneapolis, so for me the subject of Molly Flammare was a blank slate. I think that was a blessing: for that reason, I could see her for what she was. And the reality was enough to put any story to shame.

I was fifteen. I'd been orphaned a couple years back, Dad taken by the Germans at Omaha Beach, Mom by tuberculosis. But I wasn't going to any orphanage, so I left Chicago for Minneapolis and took to playing my dad's trumpet at the corner of Lake and Garfield. Apparently I had talent, 'cause people threw me enough coins every day to buy a hamburger at Charlie's Diner, and sometimes a lot more than that. So I kept playing, and things were looking up. But then Johnny Icarus sent some punks to pay me a visit.

They were just kids, high-school dropouts with too much time on their hands. They came to me on a July morning when people had yet to come out in full force, and there were only a few nickels in my hat.

"How you doin', kid?" said one. I looked around, and smelled trouble right away. There were four of them, surrounding me on all sides.

"Who wants to know?" I asked, trying to sound tough.

"Johnny Icarus," said the same kid. "That's who."

"Never heard of him."

The kid shrugged. "He's new to this town. But he wants to make a good impression here, really wants to help people. In fact, he looks at people like you, and he sees someone in need of . . . protection."

I stifled a groan.

"How much?"

The kid smiled. "Cut to the chase. Johnny Icarus likes that. Well, just for today—" He reached for my hat. "—we'll only take what you got right now. But our going rate is ten per—"

I kicked him in the face, picked up my hat, and ran like hell.

Maybe that was stupid. What was really stupid was running away from Charlie's Diner, where Charlie could protect me. But there was nothing I could do about that, and as I ran it became clear I was falling right into their trap.

Three more kids ran up to head me off. I ducked down an alley—where four more kids waited for me.

I stood there, clutching my trumpet. They would probably just rough me up; I could survive that. But they would trash the trumpet too, and that was my only way to make a living. Where would I get a new one? Charlie? I didn't think he could afford it. And what would I do next time this happened?

"Hey," said a voice from the other end of the alley. "Why don't you pick on someone your own size?"

A man stood there, holding a two-by-four. By his clothes, I guessed he was down on his luck. But it looked like he knew how to use that two-by-four, and I was taking any help I could get.

The gang leader whipped out a switchblade. "You think you can take on all of us?"

"What the hell." The newcomer tapped the two-by-four in his palm. "I got nothing to lose."

I braced myself. I still didn't like the odds—but then something happened that made the odds irrelevant.

Suddenly, the sunlight dimmed—looking up, I saw storm clouds that looked like they'd been there forever. A cold wind blew through the alley, and I shivered like it was the dead of winter.

"Leave them alone, boys," said a woman's voice from the other end of the alley, opposite from Mr. Two-by-four.

Peering into the wind, I saw her for the first time.

She was tall. Good God, she was tall, the kind of tall that had to duck through doorways. The way she stood said she knew exactly what she was doing. But her face didn't say much of anything. It was hidden under the brim of her hat.

She stood in the alleyway like the cold and wind weren't even there.

The gang leader hesitated, weighing his options. He decided on the safe route.

"L-look, ma'am, we . . . we don't want any trouble . . ."

"'Course not." She had a deep voice that could hold a stadium's attention with a whisper. "The only one who wants trouble is Johnny Icarus. That's his name, right?"

No one said anything.

"Beat it," she said. "And tell Johnny that Molly Flammare sends her regards."

And those kids beat it, like the proverbial bat out of hell.

She just stood where she was. She might not even have been looking at us. The wind still screamed in our faces, and the brim of her hat still kept her face in shadow. Then, without a word to either one of us, she left the alley. And just before she turned the corner, she reached up with one hand, made a sweeping gesture at the sky, and it was sunny again.

Sunny again. Just like that.

I looked at Mr. Two-by-four. We both wore the same expression, like the rug had been pulled out from under us. Then I ran after Molly Flammare.

I'd half expected her to be nowhere in sight when I came onto the street. But there she was, strolling down Lake, her burgundy dress standing out against the gleaming concrete. She walked pretty slow, but the length of her stride meant she was already a long ways down the block.

"Ma'am?" I shouted, running to catch up. Behind me, I heard the footsteps of Mr. Two-by-four. "Ma'am?"

She turned as I practically skidded to a stop beside her.

Her clothes said money. They also said autumn, like she was ready for a walk in a windy park in October. Her burgundy skirt hung below her knees. Her matching jacket had sleeves hanging to her wrists, and she wore black leather gloves. The front of her jacket was unbuttoned to her waist, revealing a black turtleneck sweater. Her hat, wide-brimmed and worn at a tilt, sat on a mane of hair the color and shine of polished wood.

Her face was a mask. Not really a mask, but it didn't show anything to anybody unless it really wanted to. Looking back, I realize that her face was just another part of her clothing. It was a way of protecting herself against the world around her.

"I . . . I just thought I should, uh, thank you for helping us out back there . . . um . . . we really appreciate it. Thanks. Ma'am."

I got the jitters under her gaze, like I was back in school reciting Tennyson to the teachers. But when I was done stammering, she gave me a smile. It was a beautiful smile, warm and honest, but sad, the kind of smile that's directed at memories.

"You play a good trumpet, kid." She reached down and took it from me, turning it over in her hands. "Sometimes I can hear you from my apartment uptown." She looked at me. "What's your name?"

"Tommy," I said. "Tommy Gabriel."

"Gabriel." She smiled at the trumpet. "How appropriate."

I didn't know what she meant by that, but if she was smiling, I was happy.

She gave the trumpet back, and looked at Mr. Two-by-four.

"How about you? What's your name?"

"Blatta, ma'am." A tired voice, dead tired. "Jimmy Blatta."

Something about that name made her look at him long and hard. When she asked, "You play anything?" I got the impression she was buying time to think.

"No, ma'am," said Jimmy Blatta. "I'm just a soldier, back from the war, looking for a job. If you could tell me where to find one, I'd be grateful."

Molly looked him over a moment longer, then made up her mind. "You stood up for the kid. I like that. Here's a little something for your trouble." She handed him a ten-dollar bill, and a box of matches. "I own a supper club on Lyndale. The address is on the matchbox. Go there around five and ask for Louis. He'll set you up with something."

Jimmy Blatta took the matchbox, and the ten-dollar bill, and the clouds left his face just like Molly had waved her hand again. "Thanks," he said.

Molly looked at me. "Might not be a good idea for you to play on the street for a while. How'd you like to play for me?"

I gaped at her like an idiot. "You mean . . . at the club?"

"Sure." She smiled, and handed me another matchbox and ten-dollar bill. She probably guessed I hadn't even seen a whole ten dollars before, and figured what the hell. "Have Jimmy bring you along at five. I'll have Louis set you up too." She tugged the brim of her hat. "Later, boys."

I stopped her. "Ma'am?"

She looked back. "What?"

"How . . ." I shrugged. "How'd you do all that back there?"

She smiled.

"You wouldn't understand, kid. Most of it's just smoke and mirrors anyway. See you at the club."

Then she walked away, slowly, but her legs carried her far with each stride.

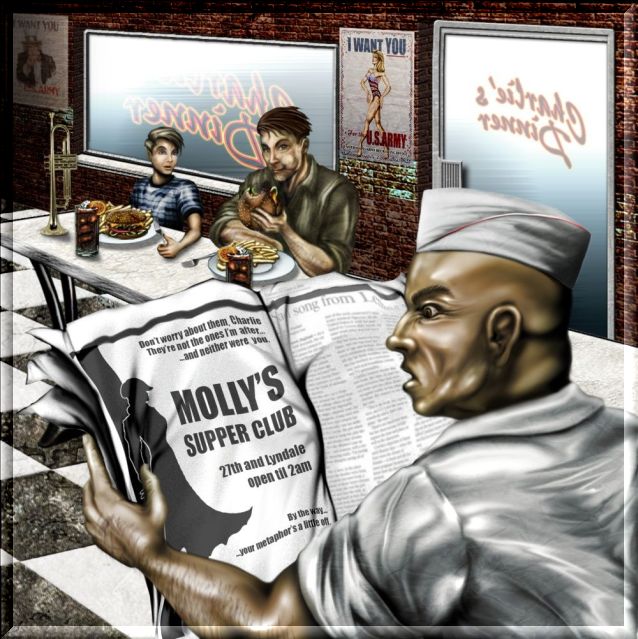

I treated Jimmy Blatta to lunch at Charlie's. I figured I owed him that much, even though it was Molly who saved my bacon.

Charlie's Diner was your typical greasy spoon, but it was the closest thing to a home I'd known since leaving Chicago. The first thing you noticed walking in was the smell of burgers on the grill. I never smelled burgers like that anywhere else—Charlie said he had his own special way of cooking them, but he wasn't telling anyone, not even me. The walls were decorated with recruitment posters with leggy dames telling you to join the Army, or the Navy, or the Air Corps. ("You know, I joined the Navy because of that girl," a guy told me once. "Spent the war on a submarine with ninety other poor slobs.") And the radio was always on. Charlie turned it way up whenever Judy Garland started singing.

From the look Charlie gave me when I paid him, you'd think he never saw a ten-dollar bill either. But when he heard who we got it from, he nearly dropped our burgers.

We watched as Charlie carefully put our plates down, then gripped the counter with both hands. It was a minute before he looked up and asked, "How'd you two get mixed up with her?"

We told him. Hell, we'd been waiting to tell him. When we finished, Charlie nodded like he'd heard that story before. Then he leaned real close and whispered, "Boys? Trust me on this. You don't want to get involved with Molly Flammare."

I wanted to ask why not, but that was a stupid question. I'd seen what she could do with my own eyes; even a kid like me could tell she was dangerous. But Jimmy was older. He knew what questions to ask.

"They tell stories about her, don't they?" he said.

Charlie laughed, but he didn't think the joke was funny. "You better believe it. You hear them mostly at two AM, when people come to the diner for a place to hide. You can't believe all of them, though." He picked up a newspaper, and began paging through it. "Some stories say one thing, others say something else."

"So tell us the one that happened to you," said Jimmy.

Charlie didn't look at him. He didn't look at the newspaper either.

"C'mon! Nobody gets that scared at a bunch of stories! What'd she do to you?"

Charlie stood where he was, not looking at us, or the paper. Finally, he put it down, and took a deep breath.

"You're right," he said. "You're both new here, and you really should know about this. Okay. Here's what happened.

"I had a brother once. His name was Eddie. Wasn't much of a brother, though. Hell, he wasn't much of a human being. Guy just didn't know how to stay out of trouble. And consequences didn't mean a damn thing to him. He was in and out of jail I don't know how many times, and when he got out, he went right back to the same old routine.

"A couple years ago, I heard that he'd raped some girl who wasn't even out of high school yet. The cops came here and asked me where he was. I told them I didn't know, and that was true. I said I would call them if I found out, and that was true. And wouldn't you know it, not even two hours after they left, here comes Eddie, parking his car up front and sauntering through the door like he was king of England.

"I told him I was going to call the cops. He knew I wasn't kidding, so he ran back to his car. I reached for the phone, but by then it was too late—for Eddie, I mean. Because Molly was waiting for him.

"That thing you saw her do in the alley? That's nothing. They say lightning won't hit you if you're in a car, but it hit Eddie. Because Molly wanted it to.

"She sprung for the funeral afterward. Nothing fancy, but respectable. But it had to be closed casket. All that was left of Eddie was some black stuff that looked like it was scraped off a barbecue grill. Parts of that car glowed red an hour after she left."

An eerie silence fell over the diner. It was Jimmy who broke it.

"Look, Charlie, I know he was your brother and everything, but it sounds like he had it coming. I mean, so Molly has a mean streak for those who deserve it. That doesn't make her a monster."

Charlie shook his head. "There's other stories, remember? And not all of the stories are true, but they all . . . feel like the truth, you know what I mean? And one thing they all say—" He wagged a finger. "—is that anyone who gets involved with Molly Flammare winds up dead."

Jimmy and I looked at each other, then back at Charlie.

"Maybe not like Eddie," Charlie went on. "But dead is dead. She's like a spider!" He held up a hand with the fingers curled. "Sitting in her web. Waiting for flies to buzz too close."

Then he realized what he was doing, and pulled himself together. He picked up the newspaper again, and paged through it. "Look, what you do is your business," he said. "But I'm giving you free advice here, and I'm advising you to stay away from—"

Then he saw something in the newspaper, and went white as a sheet.

The paper fell from his hands. He stared at us wide-eyed, his mouth opening and closing like a fish.

"Smoke break," he finally got out. "I need a smoke break." He reached under the counter and brought out a pack of cigarettes. Then he took off through the back door like greased lightning.

Jimmy went around the counter and picked up the paper to see what had spooked Charlie.

"Oh, God," Jimmy said. "Look at this."

I saw a full-page ad showing the silhouette of a woman leaning against a wall, a woman who could only be Molly Flammare. The ad read:

Don't worry about them, Charlie

They're not the ones I'm after . . .

. . . and neither were you.

MOLLY'S

SUPPER CLUB

27th and Lyndale

open till 2 AM

By the way . . .

. . . your metaphor's a little off.

In the end, Jimmy and I went to Molly's. The way we saw it, Charlie's brother only got what he deserved, and we hadn't done anything like that. And Jimmy really needed that job.

Not that we didn't have misgivings. Anything that spooked Charlie like that was something to look out for. So Jimmy and I agreed to mind our p's and q's around her.

Molly's Supper Club was about what you'd expect—big and classy, like Molly herself. You felt like you had to be in a tuxedo just to be there. If you stood on the marble floor, you could see your reflection staring right back at you. If you stood on the carpet, you felt your feet sink an inch deep.

A guy came out to meet us, saying his name was Louis. "And you must be Tommy!" he said, ruffling my hair. I hated it when people did that. "Be with you in a second, I gotta set your friend up here." He shook Jimmy's hand. "Mr. Blatta, sir. Molly told me what you did for Tommy here. You're a real stand-up guy."

"I try to be."

"I understand you were a soldier in the war?"

"I was in the Army. Medically discharged."

"Which unit?"

"Eighty-seventh Infantry."

Louis nodded. "My son was in the Fifty-third. Didn't come back."

"I'm very sorry to hear that, sir."

"Yeah, well. Anyway, Molly asked me to set you up with a job. You up to waiting tables?"

"You know what they say about beggars and choosers."

"Good answer. It's not a bad job; you're on your feet most of the time, but the tips are decent. I'll get you into some threads." He pushed Jimmy towards the kitchen door. "Be with you in a minute, Tommy! Go ahead and take a look round!"

So I was all alone with the tables and the chairs and the bandstand on the stage. I hadn't been in a place that quiet in years.

I went up and stood at center stage. They would probably just make me another member of the band, but I could dream, couldn't I? Here I could be the center of attention. No cars roaring by, no talking, just me and my trumpet, and the spotlight.

I stood there, looking around. Then I raised my trumpet, and I played "Moonlight Serenade."

For those few minutes, I was the only person in the world. Playing the trumpet took no effort at all. There's never any effort when you're doing what you want to do, what you're meant to do. At least you don't notice it. I closed my eyes, and while the song lasted, there was only me, and the soaring notes.

I let the last note linger, keeping my eyes closed as the memory of the song soaked into the walls, and into me. And when I opened my eyes, there was Molly Flammare standing in a doorway.

The light shone behind her, so I couldn't see her face. But there was a smile in her voice as she said, "You're hired, Tommy."

I ducked my head. "Thanks, ma'am."

Then Louis and Jimmy came in through another doorway, Jimmy decked out in a brand-new monkey suit. "What do you think, Tommy?" he said.

I grinned. "Looking good, Jimmy." In the back of my head, though, I got a little worried. Was I going to have to wear one of those things?

"Kid, was that you playing that trumpet?" Louis asked.

"'Course it was," said Molly as she sauntered into the room. "You think I'd tell you to hire just any old bum off the street?" She stopped in front of me, and looked me up and down. Standing on the stage, I was almost at eye level with her.

"You got anything in his size?" she asked Louis.

"No, ma'am. We'll have to buy one custom made."

Molly smiled, and ruffled my hair. "Don't worry, kid. The suit's on me."

That's how I started my new job at Molly's. I met the band a couple hours later. They listened to me play, and just like that, I was one of the boys.

We played five nights a week, with Sundays and Mondays off. The monkey suit drove me nuts at first, but I got used to it. Having all those people looking at me also took some getting used to, but I learned to shut them out of my head and focus on the song. In time, I learned to enjoy myself.

And boy did Jimmy Blatta's prospects improve. He became the go-to guy on the staff, he worked so hard. He was just glad to be working, able to put money in his pocket and food on his plate. We didn't get much chance to talk during work, but we would nod at each other across the room on occasion. There was one time he seemed a bit under the weather—I found him in the restroom splashing water on his face—but other than that, he was fine.

Molly gave both of us apartments in the same building. This made me a little nervous—I was making more money than I'd ever dreamed of, but could I afford an apartment in this building?—but Molly said it was on her. I wondered if she was worried about Johnny Icarus—and then he showed up at our front doorstep.

I'd walked into Jimmy's room one day to say hi, and I saw him at his window, which looked down at the front of the club.

"Hey, Jimmy—"

"Sh!" he said, and beckoned me to the window.

I looked down and saw Molly, standing in front of the entrance like she was guarding it. In front of her, climbing out of a shiny black limousine, stood three men dressed in pinstripe suits and red ties.

The two on either side had fists the size of cement blocks, maybe to compensate for the lack of a neck. The one in the middle was the kind of big that had to step sideways through a door. His huge head swiveled slowly from side to side, looking at everything as if he owned it. But Molly wasn't impressed one bit.

"This is an exclusive club, Johnny," she said. "You're not welcome here."

So that was Johnny Icarus?

"Not welcome here?" Johnny echoed, indicating his limo and his bodyguards with a sweep of his gut. "Am I missing something? Rest assured, madam, I simply come here for mirth and merriment—and let me add that I am a generous tipper."

Molly shook her head. "It's a question of reputation. I don't like the way you operate. Stop muscling in on the mom and pop businesses, and we'll talk. Until then, I'm going to have to ask you to leave."

Johnny glared at her. "Are you telling me how to do business?"

"In this town, you're damn right I am."

Johnny took a step toward. "Now see here—"

Molly thrust her fist into the air, and a thunderclap boomed so close I nearly jumped out of my skin.

"Let's see if that improved your hearing," Molly said as the cold wind blew around her, and storm clouds boiled overhead. "I don't like what people tell me about you. Until I do, you're not getting into my club."

One of Johnny's goons took a step toward Molly, but Johnny waved him back.

"You haven't hurt anybody yet, Johnny, so I'm still going to give you a chance. Either stop leaning on the mom-and-pops, or leave town. The sooner the better."

Johnny Icarus held himself very still. He held his gaze on Molly, but she looked right back at him.

Finally, Molly won the stare-down. Johnny looked to his two goons and jerked his head toward the limo. They entered it, and drove away.

A lot of people were telling that story the next day, believe me. But as time wore on, and nothing happened, we soon forgot about it.

We learned a little more about Molly herself, too. Every so often she would come down to the club, not every night, but enough so we wouldn't miss her. She had this special table reserved just for her; no one could sit there even when she wasn't around. It had a ticker bolted to it, like the kind investors use to keep track of their stocks. Only it didn't keep track of stocks as far as anyone could tell. Most of the time it didn't even work, even when Molly was there. But every two or three days, it would start ticking, and spit out a foot or two of tape.

When Molly wasn't there—usually around the daylight hours—me and Jimmy Blatta would take a look at it. It wasn't any language I'd ever seen. I thought it might be Chinese, but Jimmy said that wasn't it. We even asked Louis about it once, but he said he didn't know either.

When Molly was there—she'd be sitting at her table, listening to the band—she would pick up the tape and look at it. Then she would get up and leave the club. No one knew what she did during those times, not even Louis, or if he did know, he wasn't telling. Me, I liked to think it was that ticker told Molly I was in trouble with those boys in the alley. When she came back, sometimes she was in a real bad mood. And when that happened, me and Jimmy always noticed it was raining outside.

But that only happened once in while. Most of the time Jimmy was happy to have a job, I was happy to play trumpet, and Molly sat at her table.

One night when the place had closed, Jimmy was busy wiping tables, I was sitting on the stage with my trumpet, when Molly walked in. She wore white this time, white skirt and jacket over the black turtleneck and the black gloves, and for no reason I could think of, this seemed like a special occasion. "Evening, ma'am," I said, but she had her eyes fixed on Jimmy.

She walked up to him. He stopped wiping the table, and looked up at her.

"Hi, Jimmy."

"Ma'am."

"Working hard?"

"I suppose so."

She took his hand. "Sometimes you work too hard. Come here."

And she led him onto the dance floor.

I was floored. I'd never seen Molly do anything like this, or heard of it. On their nights off, sometimes the boys in the band would look into their bottles and wonder out loud what sort of man would get hitched up with Molly Flammare. He would have to be Superman or Captain America, or else he'd have to settle for living in Molly's shadow, because more than anything else, Molly had guts—and class. Somebody wondered if Louis was Molly's man, but I'd never seen them look at each other that way.

But then, never in my wildest dreams did I think she would have an interest in Jimmy Blatta.

"Tommy," Molly said. "Play a little something for us."

It took me a moment to pick my jaw up off the floor. Then I raised my trumpet, and began to play.

It was just like my first day at Molly's, only this time, even I wasn't there. It was just the song, and Jimmy Blatta, and Molly Flammare, and it was like they were flying.

You'd think a man dancing with a woman who stood head and shoulders above him would look pretty funny, but not here, not with Molly. It might have been that Jimmy was a pretty good dancer—when the band was doing practice sessions, I'd seen him do some pretty neat moves with a mop, just for laughs—but it might have been Molly too. I wouldn't put it past her to know how to give a man his dignity. Like I said, Molly had class.

When the song was over, I put down my trumpet, only then realizing how tired I was. Molly and Jimmy came down to earth, not saying anything, just looking at each other.

Molly reached up with a gloved hand, and caressed his cheek. "Good night, Jimmy," she said. Then she walked out of the room.

Jimmy stood there for I don't know how long. I watched him. It looked like he was about to cry.

"Jimmy?" I said. "You okay?"

"Yeah," he said. "Yeah, I'm . . . look, kid, no offense, just beat it, okay? I need to be alone for a while."

I said, "Okay, Jimmy," and I left the same way Molly had gone.

When I entered the hallway, I saw Molly waiting at the elevator.

All of a sudden I wondered if this was what Charlie meant when he said everyone who got close to Molly wound up dead. Was she starting on Jimmy now? Was she luring him to her web, only to . . . what?

Maybe I should have done my wondering someplace else. Because Molly turned and saw me.

"What's on your mind, Tommy?"

I stood there with my mouth open, just waiting for any flies who might want to set up shop.

"I . . . uh . . . nothing, ma'am. Good night."

"Tommy." She sat on the leather-cushioned bench behind her. "Come here."

I did. God only knows why. My feet moved like they had minds of their own, and there I was, standing in front of Molly.

"Talk to me."

But I couldn't talk. What the hell could I say?

"Ma'am . . . Look, you really got to Jimmy back there, all right? He can barely think straight. And I consider him a friend, ma'am. And I'd hate to see him . . ."

That's all that would come out. But it seemed to be enough.

"You're right to be worried," said Molly. "Some dames will do that sort of thing just so they can rip a man's heart out. Some guys will go straight through hell and not think twice about it, but get them by the heart, and they wish they were dead. But that's not why I did it, Tommy. Jimmy's come across some hard luck, and I thought he deserved a little more than he's got. He wants to be something, Tommy. More than that, he wants to be the right kind of something. And when—"

She stopped herself. I have no idea what she was going to say.

What she said instead was: "Don't worry about it. Whatever's going to happen to Jimmy, it's not going to come from me."

The elevator opened, and Molly stood up.

"Good night, Tommy."

Things went back to normal after that. Well, sort of. To say nothing had changed between Jimmy and Molly would be lying. When they passed each other in the club or in the hallway, she would give him a smile and a "Hi, Jimmy," and he would say, "Ma'am," in tones of hushed reverence. Once I even caught them talking in the elevator lobby. I couldn't hear what they said, but Jimmy's face told me he had something big on his mind. Then Molly reached up and caressed his face with that gloved hand of hers. I heard her say, "Later, Jimmy." Then the elevator opened, and she went up to her apartment.

But on this day in particular, Molly wasn't anywhere in the building. The foot or so of tape hanging from the ticker on her table gave us some clue as to why she'd gone.

"Why do you keep looking at those things?" Jimmy asked me. "Nobody can read them except Molly."

I shrugged. "Just curiosity."

"Hey, we haven't been to Charlie's in a while. What do you say we go and see how he's doing?"

"Sure." It was our day off, and I was itching for something to do. "I'm in the mood for a burger."

We walked, since we weren't in any hurry, and it was a nice day out. We weren't paying that much attention. If we had, we might have noticed somebody following us.

When we came in, Charlie acted like it was Christmas morning. He shook our hands, asking how we were doing and grinning to beat the band. We asked for a couple hamburgers, and he said sure, it was on him. We'd come in the dead hours before the lunchtime rush, and he had nothing better to do.

"So . . . you still working at Molly's?" We could tell it was still a touchy subject with him.

"You bet, Charlie," Jimmy answered. "Nothing's happened to us, either. Life at the diner been treating you good?"

"Can't complain," said Charlie as he plunked a couple Cokes on the counter. "Business has been pretty steady. But I hear—"

The front door jingled, and in came Johnny Icarus and his two goons. Behind Johnny stood a kid. It was the same kid who cornered me in that alley when I first met Molly.

Johnny pointed at me. "This the kid, Joey?"

"Yes sir, Mr. Icarus. That's him."

"Young sir," said Johnny as his gut swiveled to face me. "I will thank you to come with us."

"What do you want with him?" said Jimmy.

"I believe he works at a certain establishment," said Johnny, "called Molly's. I wish to ask him a few questions about the proprietor."

"Then ask them here," said Jimmy, "or ask me. The kid doesn't know anything that I don't."

"Look, gentlemen," said Johnny as he spread his hands, "I'm willing to make it worth the boy's while. I'll give him anything he wants, chocolate bars, baseball cards, I'll even pay for his hamburger—"

"Kid? You want to go with him?"

"No."

"Then he ain't going!" said Charlie as he raised his shotgun.

Poor Charlie didn't stand a chance. He should have known they wouldn't turn tail and run at the sight of a lousy shotgun; he should have just started blasting. But he hesitated, and that gave one of Johnny's boys enough time to take out a gun and shoot Charlie between the eyes.

Jimmy took his Coke bottle by the neck and smashed it on the edge of the counter. Then he jumped at the guy who'd shot Charlie and drove the sharp edges into his throat.

That left the other guy. He had a gun too, and he shot Jimmy in the back.

I felt like I'd been punched in the gut. I ran to Jimmy and shook him, calling his name over and over, crying my eyes out. Then I felt Johnny Icarus's hand on my shoulder.

"As I stated earlier," he said, "I wish to ask you a few questions regarding your employer."

They stuffed me in a car, and kept my head down. The goon Jimmy killed must have been the one who usually drove, because this guy damn near flipped us over a couple times. When we stopped, we were in some sort of warehouse. They took me to a little office in the corner, and sat me on a chair across from some guy reading a newspaper. When he put it down, I found myself looking at a priest.

"Father Jacques," said Johnny Icarus. "Here is young Mr. Gabriel, as promised."

Father Jacques mopped his forehead with a handkerchief. "I'll get to work on him right away," he said.

Now, I've heard of mob lawyers, mob accountants, even mob doctors. But a mob priest?

Johnny left, and the priest started asking me questions. What books does Miss Flammare read? What sort of furnishings does she have in her apartment? Have you ever seen a pentagram, either in her building, or on her person? I asked him some of my own questions, like what the hell was a pentagram? He stared at me a moment, then he got up, knocked on the door and asked for a pencil and paper. When he got them, he sat at the desk and drew a five-pointed star with a circle around it. He was real nervous about it, too.

"That's a pentagram," he said. "Have you seen it?"

I shook my head. "No."

He tore up the drawing, and crossed himself.

Then, there was a knock on the door. Mopping his forehead, Father Jacques got up and answered it. I saw Joey reading a newspaper before the priest shut the door behind him.

Seeing that newspaper gave me an idea. Father Jacques had left his paper on the desk. I grabbed the paper and started looking through it.

There was a full-page ad on page three:

You're finally catching on, kid.

Still got that box of matches I gave you?

MOLLY'S

SUPPER CLUB

27th and Lyndale

open till 2 AM

And don't touch anything metal.

A roll of thunder outside drove her point across real good.

I still had the box of matches in my pocket. But before I could figure out what to do, the door handle jiggled. I put the paper back, and sat down.

"Just give me five more minutes with him, Mr. Icarus," said Father Jacques as he came in.

Johnny closed the door without a word.

Father Jacques looked at me. I swear to God his eyeballs were sweating.

"Is there anything you can tell me?" he whispered. "Do you have any idea how she does what she does?"

I spread my hands. "Far as I can tell, she just . . . does it."

"Can you even tell me how she might be found?"

Thunder rumbled again. I jerked my thumb at it. "Sounds to me like she's coming for you."

He looked up like he was expecting lightning to come through the roof.

"Does she . . . treat you well?"

"If you're good to her, she's good to you. I wouldn't want to be the guy who killed Jimmy right now."

He settled down a little, thinking.

Then he asked: "Would holy water work against her?"

Something about the way he said it made me answer: "About as good as anything else."

He nodded, opened the door, and went through. "Mr. Icarus?"

He told Johnny that he had to get some holy water back at the church. Johnny said he would take Father Jacques there himself. I heard them leave in the car.

That left me with Joey and the goon who killed Jimmy.

Well, obviously I was supposed to start a fire. But with what? There was a wastebasket by the desk, but I didn't think that would be big enough. Then I saw the filing cabinet. Oh yeah, there were lots of papers in there. I struck a match and set a fire in all the drawers.

When the papers were good and burning, I called for help. When he heard me, the goon started swearing. He had to know I was up to something, but Johnny wanted me alive. So he opened the door.

"I'm gonna wring your little neck, kid!" he bellowed. And I got more than a little nervous. I knew Molly would save me, but I began wondering how. And when.

The goon took one step towards me. Then he stopped.

He looked at me like he was trying to remember something. Then he fell flat on his face.

A switchblade stuck out of his back. I looked up, and saw Joey.

I wondered what made him help me. Then I remembered.

"You were reading the newspaper."

Joey nodded, very slowly, like he was afraid he would fall apart.

"I'm . . . I'm very sorry for what happened to Jimmy and . . . and Charlie."

I didn't know what Molly said to him. Maybe I didn't want to know. I ran through the office door and out of the warehouse.

It was raining. I was just in time to see lightning strike not fifty feet away from me, and when I opened my eyes again, all four tires had been blown out on Johnny Icarus's car. It swerved in the mud, turning around a couple times and almost flipping over before it finally stopped. And there, about fifty feet beyond that, stood Molly, right in the middle of the road, like the wind, and the rain, and the lightning weren't even there.

Johnny climbed out of the car, dragging Father Jacques by his starched collar. He held the priest in front of him with one hand while the other held a Tommy gun.

"You crossed the line, Johnny." Even with all the wind and thunder, I could hear every word Molly said. "You shouldn't've done that to Jimmy and Charlie."

Johnny peeked over Father Jacques's shoulder. "You wouldn't hurt a man of the cloth, would you?"

Molly reached out with one hand.

"If I had to."

Father Jacques screamed as the lightning struck, and I flinched away again. But when I looked back, there lay Father Jacques face down in the mud, still screaming, still blubbering, still alive. A flaming pile of flesh was all that remained of Johnny Icarus.

Father Jacques pulled himself up to his knees. He folded his hands and prayed. He blubbered and shook so much he might have been saying "Now I lay me down to sleep" for all I knew. But he stayed there on his knees, still praying, until Molly walked up to him, and he looked at her.

"Get out of here," Molly said. "I don't ever want to see your face in this town again."

He didn't need to be told twice. He got up and ran, never looking back. Last time I saw him, just before he disappeared into the rain, he was still running.

Then I heard somebody else's footsteps. I turned and saw Joey running for it from the warehouse.

"Not you, Joey!" Molly shouted. "Come here!"

He stopped dead in his tracks. I thought he looked terrified before.

"I said come here, Joey!"

Slowly, staring straight at the ground, he turned and shuffled through the mud toward Molly.

Just then it dawned on me that I felt sorry for him. That was probably why I called out to him, "Joey."

He stopped and looked at me.

"If she wanted you dead, you would be."

And I walked with him to where Molly stood.

She knelt down and grabbed his arm.

"You've been hanging out with the wrong crowd, Joey. But that's going to change because you'll be working for me from now on. Meet me at the club at seven tomorrow morning, and I'll set you up with a job. And if you're not there at seven, I'll come looking for you. You got me?"

"Y-yes, m-ma'am."

"Look at me, Joey."

He didn't.

"Look at me!"

Then he did.

"Don't worry about it," Molly said. "Keep your nose clean, and you'll be fine." She stood up. "Now get out of here."

As Joey ran off, the whole thing came flooding back to me, first Charlie's death, then Jimmy's. I started crying again.

"I'm sorry, Molly. Guess we should've checked with you before going to Charlie's."

Molly shook her head.

"I'm sorry, Tommy. Even I can't be everywhere at once."

Then we heard a car engine, and we saw a pair of headlights followed by a beautiful silver-grey car with Louis in the driver's seat. Molly opened the door, leaned in, and said, "Take us to the hospital, Louis."

The hospital?

"You mean . . . Jimmy's still alive?"

Molly just said, "Get in, Tommy."

As Louis drove, Molly told me what happened: after Johnny left the diner, Jimmy dragged himself on his stomach, smearing blood all over the place, to the curb, where he managed to hail a cab. The cabbie wanted to take him straight to the hospital, but Jimmy said no, take him to Molly's. So that's what the cabbie did. When they got there, Molly was still gone, but Louis was there, and he knew how to get a hold of her. But he sent Jimmy to the hospital first.

When we arrived, Molly knew exactly where to go. A doctor stood waiting for us outside a hospital room.

"How is he, Danny?" Molly asked.

"He's lost a lot of blood, Molly. He won't last the night." He looked through the door. "'Course, he wouldn't have lasted much longer anyway."

"What do you mean?" I said. "What's he talking about, Molly?"

Molly only said, "Tell him, Danny."

Danny looked at me. "You know Mr. Blatta was in the Army, right?"

"Yeah. He said he was medically discharged."

"That's right. But he probably didn't tell you that he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. They said he had about six months to live. So they sent him back home from Europe." Danny shrugged. "He never even saw combat."

Molly looked over to where Jimmy lay. "Can we talk to him?"

"Sure."

Jimmy looked even worse than I expected. I had no problem believing he wouldn't live to see the morning. But when he opened his eyes and tried to smile, he mostly succeeded.

"Tommy," he whispered. "You're okay. That's good."

"Yeah, Jimmy," I said. "I'm okay. And Johnny's gone now. Molly took care of him."

He looked at her.

"Molly . . ."

She shook her head. "Oh, Jimmy. You didn't have to prove anything. Not to me."

"Not to you, maybe. But there's some things a man's got to prove to himself, you know?"

Molly didn't say anything. It looked like she couldn't say anything.

"Molly . . . whenever I asked you . . . that question . . . you always said, 'later.'" He closed his eyes, and opened them again. "Can 'later' be now?"

Molly stood stock still. It was like time itself had stopped.

Then she said, "Sure, Jimmy. You can have it now."

And she took off her gloves.

This really spooked me, because I had never seen her do that before. She had smooth, milky-white hands that looked like they belonged on a statue. And she leaned over Jimmy Blatta, she placed her milky white hands on either side of his face, she lowered her lips to his, and they shared a long, slow kiss.

I stood there and watched. Again, it was like I wasn't even there. There was only Jimmy Blatta, and Molly Flammare, and they were dancing one last time.

When Molly pulled back, Jimmy's face had changed. He wasn't smiling, but it was really peaceful, like everything was going to be okay. Molly looked at that face, not saying a word. Then she bit her lip, and left the room in a hurry.

The doctor went over to Jimmy, and pulled the sheet over his head.

I looked at him. "Aren't you going to check his pulse or something?"

"He's dead, kid," said the doctor. "Trust me."

I looked at him a moment longer. Then I went into the hallway.

Molly sat on one of a row of chairs standing against the wall. She had her gloves back on. When I sat down next to her, she said, "Poor guy. Never had a chance. Just couldn't win for losing."

I didn't know what to say. But Molly went on talking without me: "And the only thing I could give him was . . ."

She waved a hand at the room we had just left, shaking her head. Then she began to cry.

I was only a kid. What could I say to her? "Come on, Molly. Don't cry," I said, and reached up to wipe away her tears—

Her hand clamped down on my wrist like a steel trap. It almost hurt. No. It did hurt.

"Never touch me, Tommy," she said softly. It was a gentle warning, a friendly warning, but still a warning. "No one can ever touch me."

It wasn't until then that I knew why Molly always wore gloves, why she dressed for autumn in the middle of summer. Only then did I know where those stories Charlie had heard came from. Only then did I understand the gift that she gave Jimmy Blatta.

I pried my wrist from her fingers. Then I took her hand, squeezing it through the glove. "We can do this, though," I said. "Can't we, Molly?"

She didn't say a word. But she did squeeze back.

We sat there forever in the hallway, holding hands, remembering Jimmy as the world went by without us. I have no idea how long we stayed like that, but when she was ready to face life again, Molly gave my hand an extra squeeze.

"Thanks, Tommy."

Joey got a job bussing tables at the club. The first month or so, he tiptoed everywhere, afraid of his own shadow, but then he learned to stop being afraid of Molly and start respecting her. Then he really turned his life around, and now he might actually turn out to be a decent human being.

I still play trumpet with the band. Sure, I could have moved on to bigger and better things. Hell, Armstrong came to town once and asked me if I wanted to play with him. Armstrong, can you believe it? But ever since Jimmy Blatta, I've noticed Molly feeling more and more down, and other than Louis, I'm about the only friend she has. And when I look at her when she's sad, I remember that the only time I've seen her truly happy is when I'm playing trumpet for her. There's no way I could take that away from Molly. So I stay at the club.

Still, I don't want from her what Jimmy did. I'm all right with just flying around her, admiring her for what she is, respecting her for what she does. I told that to Louis once, and he said I got the metaphor right.

Molly still has that ticker on the table, and she still does what it tells her, whatever that is. I think the city is her responsibility, and she's there whenever it needs her. But sometimes she needs something too, and when she does, I'm there for her.

It rains a lot more now in the city. Sometimes, at two AM when the club is closed, Louis and I hear thunder rumbling outside, and we know that Molly needs some cheering up. Then I walk onto the stage with my trumpet, and I wait there until Molly comes in, and she sits at her table without saying a word. Then I put the trumpet to my lips, and I play for Molly until she feels better, and she lets the moon come out from behind the clouds.

Dedicated to the memory of Claude Dziuk (1929-2005), my senior high school English teacher, who is now reading Shakespeare aloud in that big classroom in the sky. Jason D. Wittman

Jason Wittman is also a game designer.