The first day I said no and he left, and I thought that would be the end of it but it was not. He came back the next with the same question.

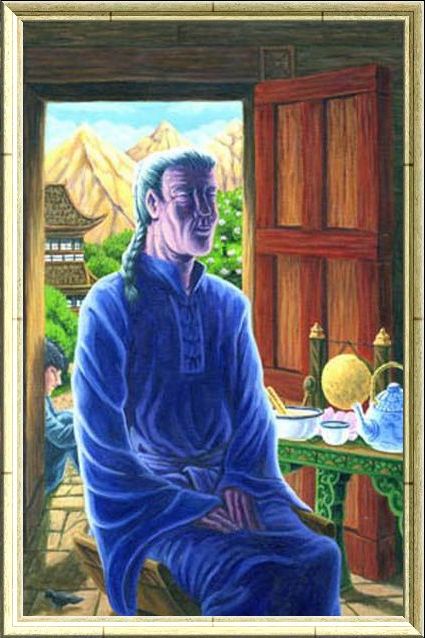

No again. One word, unmistakable. Syntactically unambiguous. Aurally distinct. Contextually obvious. Intentionally clear in every way only this time, he did not leave. He sat in front of my door instead. Later, he pissed on the side of my hut and shat at the edge of the woods. He did not do too much of either, because as far as I could tell he did not bring any food and he was nearly starving from the beginning anyway.

After that first week, his skin was stretched taught over his bones and his lips were dry and cracking. He remained sitting in front of my door. When I set a bowl of water and another of gruel outside for him, his mouth trembled and I almost smiled. "No," I said before he could ask, and I went back inside.

Through a gap between the door and the wall, I watched him eat and drink. He licked the wooden bowls clean and stacked them before returning to sit and stare at my home.

After I fed him he began to follow me around like a damaged child. Not saying anything, just watching. Stopping when I stopped, walking when I walked. I hate having eyes on me.

I have never been good with people, not even my audiences. It burns, their looks, and I feel like I am blushing even though I know my deep southern skin is too dark for any of us to know for sure, and I want to yell at them to turn and watch the other direction while they listen. I sing, I want to tell them, that is all. No show up here. No show for you to watch, just to listen. Now leave me alone.

That's what I want to tell them, only I never do. And he did not leave me alone. He asked me every day. Just once. And every day I said no.

We grew very close.

I got tired of him sitting in front of my door early on. He was a boy, a child, a youth, hardly old enough to be conscripted. He was too young for sitting. Sitting is something you have to be old, like me, to do properly. So I walked out one day and gave him the hatchet and pointed to the stack of firewood.

He looked at me like I was the idiot, so I got a piece and showed him what to do; how to split the wood, where to place the kindling. Then I handed him the hatchet again and went inside to sit properly, as only the old can do.

I rested on my pillow and poured some tea. I allowed myself a smile at the sound of cracking wood that began to filter in through the baked-mud walls of my home. It was very pleasant. I composed a song about the sensation: the sounds, the sunlight slanting in from the edges of the closed shutter, the steaming tea, my heartbeat and breath . . .

mmmmm

K'kuhmmkuhmm

muhaaashhuh

mmmmm

K'kuhmmkuhmm

muhaaashhuh

cheh, chuh, chahmuh

mmmmm

muhaaashhuh

And so on. It was a very pleasant song. I sang it often in the years to follow.

I never had so much firewood.

Sometimes the boy would speak to me even after I told him no, more to hear his voice than anything else I think. He said all sorts of things. I rarely paid attention, but still, it was comforting to hear him tell stories he had heard as a child, or talk of the dreams that seemed to come to him so often in the night.

"Master," he said once. "What are the Twelve Virtues?"

I demonstrated the respectful silence of the Third Virtue, but that did not seem to satisfy him. "Master," he said, "Sometimes I think you are deaf." His voice fell. "Sometimes I think I am crazy."

Thinking, I thought to myself, is not one of the Virtues. I wondered why that was, as evening gave way to night. Perhaps it is because one so often gets things backwards.

The boy told me why he wanted to learn to sing. "When I was young," he said, "I heard a vasya sing. It was beautiful. It . . . made me want to live forever."

Only there was much he did not say. Where had he come from, to have heard a vasya sing? Even the peasants over the hill have only heard me once, at a young couple's wedding, and even then only because loneliness had strangled me near to death that year, to where the performance seemed a small price to pay for the scent and sound of others. Was he a nobleman's son, or an illegitimate child of the Empress?

"Will you teach me?" he said, ignoring the questions that danced so clearly across my face. In the stillness that followed, he said, "They told me you taught Master When. They said you are the best." His voice cracked. "I want to hear such music again. Please teach me to sing."

I soaked in the music of the breeze until I became calm once more. Master When was never my pupil, and he could not sing. He never learned anything, and you cannot sing if you do not listen.

"There is music enough already," I wanted to say to the boy. "To think you can create more is arrogance, and to worship the vasya is to be deaf. Go to When for lessons in arrogance," I told him in my head, "as it is clear you have already mastered being deaf. Here, in my hut, I listen. Only when it is appropriate do I accompany the world in its never-ending song of joy and sadness and sadness . . . and sadness."

But I said nothing, and soon enough the boy lowered his head and began to cry. The sound was beautiful music; I had not heard anything like it since she left. It made me want to live forever, until I remembered it was I who had left her, and the guilt and sorrow and anger of my past blossomed inside me once more.

Gently, I poured my cup of tea on his head. He stopped, and the air shimmered with something half-forgotten. We were never given children.

The boy raised his head and blinked, his eyebrows moving like caterpillars. A drop of tea clung to the end of his flat nose, and I smiled. Hesitating at first, he joined me a heartbeat later.

The music of his tears had fled our hut, but there were other melodies there to replace it.

The peasants over the hill live near a legend. They barely know the half of it, but then, they barely know anything. They would shiver with fear and delight to know I once sang for the Emperor. He touched my hand—so generous! Such a privilege!

Perhaps the Empress will someday call to hear me sing as well. Could any man long endure the delight of seeing two lords of heaven in a single lifetime?

I do not think I have to worry about that.

I think of the past often, as days turn from light to gray to black. I look back at my life, and I see the nation I have long lived in as a chorus, a choir. The sounds mesh together here, then pull apart there, and everywhere there are complications. The recent civil war is one such discordant passage, now receding into the past almost as though it had never been. The Sempai have crushed the Hassau, and rice is plentiful again; what good is it to dwell on what might have been? Such fluctuations in power are nothing more than the slow turn of seasons. The only difference is that nothing changes.

Clarity always comes early, far too long before the horizon's edge turns gold again: our nation has no melody. It is hardly even a note. The night is ink-blue when I think it should be black, and for the thousandth time I realize that the boy and I alone are more than the country we live in. We are the audience that hears its note, and the orchestra that sounds it. We are all-seeing, all-knowing, all-living. We are, and a nation is just an idea less substantial than the air we breathe. Who fights to control the air?

And then I find the night is suffocating me. So I think of peasants.

Peasants know how to breathe. Sometimes I give them trinkets for their rice, and sometimes they give me rice simply because they are simple and the earth is plentiful, and I sit in my hut and realize they are more than a note and an orchestra: they know how to listen. They are a sounding-board that resonates with the pure tone of themselves, and if that is not enviable then I do not know what is.

None are poorer than the rich, and the Gods laugh at us all. I can't remember if someone said that, or if I did.

Late one night, a foolish old man overcome with thoughts of the past hugged a lonely, simple boy to his chest and wept. The boy froze in his arms, a statue, a block of ice. Then he melted and began to comfort the old man. I grew angry at him, comforting the elder when I could not, so in between my tears I stood and cursed and kicked him out the door. He could sleep outside, I muttered to myself. He could sleep.

I continued to weep. I don't remember what happened to the old man.

He was outside my door the following morning when a party arrived to request my services. The delegate in charge bowed low, offering him something, I forget what. Maybe a leg of lamb, maybe a silken robe. The boy bent over almost double and stumbled back into the door, until he was able to pound on the wood to get my attention. "Visitors," he croaked.

I stepped back from where I knelt next to the wall, peering outside through a crack. My arms and legs trembled. I like to watch. I like to sit and watch and listen to everything. But to be seen . . . is painful, always.

Sometimes, necessary.

I walked out and waived aside the golden urn or bag of incense or wooden puzzle box held out in trembling hands, and I listened to their proposal. I wanted to tell them to leave, but two people go through food twice as fast as one and I had not foreseen the boy's presence. Already my stores were growing low. So I accepted, and burned, and said nothing else. Perhaps they took my silence as wisdom. Fools and the eager often do.

The delegate beamed at my acceptance and bowed in pleasure. Behind him, his party prostrated themselves. "You and your slave will be most comfortable, Master. The finest beds, food, and wine during your visit."

"Slave?" I said. The delegate nodded—yes. He pointed. The boy. "The boy is not a slave," I said, opening the door to the hut and motioning the boy inside. Together, we crouched by the crack in the wall and watched the delegation. They deposited the holy statues or brightly-dyed blankets or fine porcelain tea cups before my door, and then they left. I had the boy bring the offerings in, then return outside to sit his vigil. Perhaps he would get the hint and leave. He was nothing but an irritating sore in my mouth, painful and impossible to ignore. I snorted to myself, and almost without realizing it I began to fill the hut with the sound of splitting wood and sunlight. I interrupted my sitting long enough to let the boy back in.

A month went by before we left for the concert. When the time came, I was glad the boy was still with me. He carried everything.

The Lord was very rich. With the sort of cleverness that comes only from true patriotism, he had backed both sides in the war. Where everyone else lost, he could only win. The blood of thousands filled his coffers, transformed by an uncaring world into silver and gold. I could feel my stomach boiling from the moment we entered his compound: there were people everywhere, and none of them knew how to listen.

"Master!" said the porter, genuflecting. I grunted and allowed him to show us to our chamber. He kept babbling as he led us, as we stepped inside the room. I told him I did not want to be disturbed, and I shut the door. It helped. His voice ceased, my stomach loosened, and I sat.

The boy looked at me, the pack still on his shoulder. He had a question, but it was not that question. I nodded. He let out a whoop and set down the pack, then was gone to explore the rich man's house.

I stayed behind, and prepared myself for the night. For the wedding, for the feast. For the performance, and their eyes.

I sat, as only the old can do.

The wedding was beautiful. The Lord was very rich, it had to be beautiful. The food was magnificent. Only two of the twelve courses contained items not tainted by meat. Two was enough.

The Lord's son, the groom, had a round face. Like the Buddha. Like a perfect orange, or an upside-down pear, or a pregnant pig's tight-stretched belly. Looking at him turned my stomach, but that was to be expected. I was not religious, and I never liked pears. He looked at me once during the dinner and smiled. His teeth gleamed like knives. He was his father's son.

After the wedding feast, those guests still able to walk followed me from the great hall to a smaller room. They sat on their pillows, elbows almost touching there were so many of them, and their eyes did not have the grace to look elsewhere. I closed my own to shut them out, and I started to sing—not a song of words, but the kind of song only a vasya can sing. A song of poetry, of life. Magic. A pale imitation of all three, but then, everything is.

I began with the blackbird. The nightingale is more renowned, but only because of an unfortunate poem by a tone-deaf poet. It is the blackbird that I find sings most beautifully, most forcefully, most perfectly. Someone in the audience sighed at the sound, careful to let his neighbors know how pleased he was at the choice. I almost ended the concert and yelled at them all.

But I did not. I was a singer. I continued to sing. I added cicadas, and someone gasped, perhaps in honest surprise, in honest praise, and I glowed at the thought until I remembered that no one is honest in the house of the rich. I shoved thoughts of past mistakes aside, and I made the room pulse with sound instead, as

the blackbird chases off a hawk. It rains, a small drizzle, the sound barely audible above the chirping of the cicadas, the crunch of a rabbit eating. A squirrel runs, chatters, leaps. Night comes; the sound of shade creeping audibly over the audience is itself a minor masterpiece. A peasant household makes dinner. Riceballs, soup, stir-fry vegetables. The sound of the scent of garlic and spices fill the air. The children get in a fight. Father yells at them—"Ayah, ayah! Hayah dah-doh! Ayah, ayah!" In his anger there is love.

One child whimpers. His sister comforts him. "Sheh sheh, hassuh hoh," she murmers. "Sheh sheh." Mother serves the food. The child stops his crying.

As the last dish is finished, the wooden bowl scraped clean by the hungry child, the dog is given a bowl of rice. The mother and father make love. The child stares into the fire as his sister listens.

They drift off to sleep, and one by one the sounds fade until it is just the cicadas and the blackbird, then just the blackbird singing through the night, under a lantern left hanging in the branches of a solemn old tree, then nothing is left but the breath of life and the slow beating of the heart of the universe, then even those are gone as the inevitable silence of eternity fills the hall.

The concert finished, I opened my eyes and was disappointed to see the audience still there. Sometimes I wished I could truly transport them somewhere else with my music; them or myself, either would do.

The nobles waited the proper amount of time, then applauded politely. The host bowed towards the stage, as was tradition, and no doubt would have a parting gift suitable for the Empress herself come the morning and our departure. He had to. It was—tradition.

I hunched my shoulders and smoldered until the last had turned their backs and left, as deaf as ever, leaving me in the room all alone except for the boy who sat with his eyes closed, rocking back and forth on his seat in time to the memory of the beating of the heart of the universe. "Meh," he said, after a moment. "Meh." With each rock forward, he repeated it. Softly, under his breath, "Meh."

It was close. It was not quite the heart of the universe. But still it was a heart, of that I was sure. I left him in the room to his meditation, and went out to the courtyard for my own. The last of the guests were gone. The servants were busy with other tasks, or asleep themselves. I was alone. Happy for the first time in weeks, I closed my eyes and listened to another concert that far surpassed my own.

If only people would learn to listen, I would never need to sing again.

We returned home. On the way he again asked me to teach him. And I again said no. I sing, I told him. I am a singer. He had come to the wrong man. Perhaps he should have found a teacher.

For about a mile after my response he said nothing. When he spoke again, his voice was thick with the past. I could tell he had been thinking of something. "In my village," he said, trailing off. "Near my village, there were trees . . ."

I thought he was going to tell me about his past. Where he came from, why he wanted so much to sing. Was his family dead? Had the war destroyed his village as it had so many of the others?

I was wrong. Shadows cast by the trees along the trail continued to caress our skin with their cooling, intermittent touch, and we said nothing else for a long, long time.

We sat inside the hut, taking turns pouring the tea and trying together to match our heartbeats to the pulse of the universe. "Teach me," he said once every day, breaking the stillness. "No," I replied. Then, our conversation finished, we would become still and listen with studied attention to the music that never ends.

And what need was there for more? He wished to learn. I wished to listen. We both enjoyed the company. I did not know where he came from, and he knew nothing of my past. But the present—oh, the present brought us close, as we took in all the subtle rhythms of the world that surrounds us all as water does fish.

What need was there for more?

I was old when he came. Six years passed, and I only became older. One day, after we finished our conversation, he said something new. He said, "Sing for me, then, Master." I had often sung for us both, when I felt in tune with the world, but never before had he requested me to.

"No," I told him. And as we sat and listened, I said it again. "No." And again, then again. "No. No. No. No." I repeated the word until it lost all meaning. Until it became a sound instead of a word.

It was my refrain, my chorus. A backbeat, a rhythm, a pulse. Not the heartbeat of the universe, mind you—just the heartbeat of me. The heartbeat of my experiences. The sound of my life. I added a second beat after it, and they completed each other like red and gold.

"Meh," I said. "No. Meh. No. Meh. No."

Against them I added the sound of hunger. Or maybe it was loneliness.

Night and day and back again; time ran around our heartbeats in circles, becoming lost and confused against the stability of their drumming. We fed each other through a door, him giving companionship and me giving gruel, and we walked together to chop firewood, and I sang to him my simple song of tea and light and life and wood that I had crafted so long ago.

I sang of eyes burning, stomach clenching, end approaching, strength failing. I sang of stubbornness, youth, joy, hope, companionship. Of poured tea, the clink of glass on plate, four nostrils inhaling steam instead of two, hot liquid sipped and experienced separate, together, complete. I sang of everything.

Through it all was the sound of our two heartbeats, slow and steady, steady, until I finally stopped singing. We sat and listened, eyes closed, as they continued to sound.

Meh. No. Meh. No. Meh. No.

I am not good with words; I am good with sound. Words are not sound. They are less than sound, they are more than sound. Words are ideas. Sounds are experiences. Both have their strengths and weaknesses. So do I. That was the only time I told him how much I loved him. That is a weakness. But he knew anyway.

He was very strong.

The boy did not give up after that.

"Teach me," he asked the following day like every other day.

"No," I said.

"Meh," he said.

We smiled together, and drank our tea.

It was Winter when I began to cough. It did not stop. Drops of blood stained my sleeves, and I sat on my pillow and sipped my tea and thought of everything we had been through over the years. Maybe, I thought, it is time I took on a student. Maybe I already had.

I began to compose again.

He still asked me every day, but it was Spring before I finished my work. His eyes glowed when I said I would teach him.

"Close your eyes," I said (they were too bright) "and

listen: you have labored

with the Patience of the Warrior Who Challenged The Sky, and you have Persevered with the Heart of The Woman Born In The Shadow Of The Reeds. Now you must Hear with the Ears of the Boy Who Would Learn To Sing. Just close your eyes, and listen.

Do you hear this? This is my song. It is not words. It is different from words. Words share only ideas. A sound is an experience.

Unh. See?

Feh. See?

Kah! See?

You must listen to my song until I finish. Remember back to the first concert you saw me give. Listen to my lesson like that. The slow silence of eternity will let you know when I have reached the end. Then you can open your eyes again, open them and tell me what you think of this song. I think it among my most beautiful. I have been composing it for many months. I hope you agree. Listening to it, I want to live forever.

Do you remember saying that?

Hear me now. I am happy. Hear the sound of my happiness:

Wheh

Hear it grow and shimmer as I tend to the stove, as I bring tea to boil. This is the sound of boiling tea:

Pahdehdehdeh

Pahdehdehdeh

Do you recognize it?

Now hear your breath, the breathing of my student:

Hseh-Whey, Hseh-Whey

Do you see how the sounds belong together? How they compliment each other like birth and death, hope and love?

Hear the sound of tea spilling into my cup. Hear the sound of my happiness,Wheh Wheh Wheh.

Before you, there was none of this. There was only the rahsheheheh of my loneliness, my ignorance of self, my fear of life. And the slowslehh, slehh,of years passing by with everything I wanted and nothing I needed. Or do I have that backwards?

Ah, I have tricked you. There is no difference.

Now hear the smell of green tea. Feel the sound of my heart as I stir in one last ingredient. Can you make out the rattle in my lungs? It has grown so loud:

Kheh-heh-heh

This is your first lesson, to listen, and it is the last. It is the only lesson you will ever need, and you know it already. I am useless. Listen to my heart, my happiness, my new understanding, my tea, the rattle in my lungs, my happiness, my heart. You see? You are a genius.

Now listen to the blood running thin in my veins. Listen to it staining the back of my teeth as I cough; it is worse now than it was before, is it not?

Hear me take a sip. No, a gulp. Hear how it washes the blood away, like the sun washing back the snow? Yes, of course you do.

Now . . . listen, as the world falls away. Listen until all is nothing, nothing but a blackbird singing through the night under a lantern left hanging in the branches of a solemn old tree. Listen as even that sound fades into the breath of labored lungs near failing, then fades further into the slow beating of the heart of an old man. Listen to my masterpiece.

Listen, boy, I only told you once, but you knew all along did you not? You knew even before I did. Know it afterward, too. It is just my weakness that keeps me from speaking. It is a strength to listen so well. The only strength the Gods have given us. I hope you have learned well the one thing I could teach. You have taught me much more.

Keep your eyes closed, Master. I don't like being watched. Just . . . listen. Listen to my happiness. Listen to the silence of eternity. Is it not beautiful?

This song will be over soon, but there are others to replace it. Listen, and sing, that is all I ask.

You will make beautiful songs, I'm sure of it.

"Master?"

He will sing well someday. Like a little blackbird.

I try to open my eyes one last time to see him before I go, but it is too late. The song has taken me someplace else. Someplace beautiful. I do not know the sounds to describe it.

Maybe I can learn them.