The little boy sat on the examination table, swinging his bare feet. His mother played with his downy hair as she spoke to the doctor. "I can't think of anything we've done differently."

"No over-the-counter medicines? New cleaning products? Herbal medicines?"

The mother shook her head each time. "No, nothing. Maybe he got better on his own. Maybe he never had it in the first place."

Miracles and spontaneous cures weren't on the top of Dr. Fellows' list of possibilities. And he knew his diagnosis had been correct. "Mrs. Allen, Cody has. . .had hydrocephalus. I wouldn't have scheduled him for the shunt today if I wasn't sure. Maybe the pre-surgery antibiotics knocked out an infection we weren't aware of. Maybe. . .I don't know. Let's watch him closely. We can reschedule if we have to."

She caressed the back of the toddler's head. "Do you think it'll come back?"

"I. . .I don't know," he said leaving the examining room.

Mrs. Allen picked up Cody's clothes to dress him, again touching his head. She put the clothes down. "What's this?" Parting the child's hair, she looked at the clear crusty spot at the base of his hairline. "Honey, what have you gotten into?" She scraped it away with her fingernail.

Grant Fellows returned to his office in the lower level of the neurobiological research department of the university hospital. He was glad the rest of the staff had gone to lunch. He would have to tell them it was true, the little boy's hydrocephalus that had distorted the shape of his head and disturbed his physical and mental development had gone poof. Marianne had taken the mother's call. Even though they all thought it was a case of maternal nerves before the surgery, his colleagues and the interns ribbed him about his "misdiagnosis." Grant tossed the folder onto the desk and sat. Routine infantile water on the brain wasn't his area anyway. He was more interested in the recent rash of cases of spontaneous intracranial hypotension.

Fourteen, so far, with more coming in every week. When it started over a year ago, the cases weren't surprising. Poor health and dehydration were responsible for all kinds of maladies. Heart disease, tuberculosis, and the little tears in a weakened brain pan that allow the drip, drip, drip of cerebrospinal fluid until the brain no longer floats on a liquid cushion but sinks into the lower opening of the skull. Grant understood how nasty and painful the deaths had been as each of the homeless were brought in from the dark sewers around the water treatment plant. Spontaneous intracranial hypotension wasn't commonly seen in the down-on-their-luck alcoholics who lost all interest in food and water in their eternal search for another drink, but it wasn't unheard-of. A group of kooks protesting the plant blamed the deaths on the treated water and pointed out the low magnesium levels of the victims reported in the newspaper. They weren't influenced by the expert opinions stating that cause of death was known and had nothing to do with deficient magnesium, which is epidemic in the U.S. population and pronounced in alcoholics. They were tree-huggers and all progress was bad to them.

When the schizophrenic bag ladies who didn't drink and the babies living with their indigent mothers in abandoned cars began coming in, he felt he had at the very least a journal article and at best a major research study with federal funding. Then all hell broke loose. Middle class Joes and soccer Moms and socialites succumbed—their brains were leaking fluid like a '68 Chevelle.

The phone rang. He heard quick footsteps from the door as Marianne ran in to answer. A minute later, she leaned into his office. "Boss, there's another one. Up in the ER."

Grant heard the screams before he pushed through the double doors of the emergency room. He pulled aside the curtain and stepped carefully to avoid the vomit splashed across the floor. A young woman writhed in pain, her hands gripping the sides of her head.

As he approached the patient, a voice called out behind him.

"Hey, you! Nobody goes in there without talking to me first."

"And who the hell are you?" He turned and saw a petite woman wearing an ill-fitting discount catalog pantsuit.

She flipped a badge open. "Detective Wilding, city police. Who are you?"

He rolled his eyes and called to one of the nurses. "Will you get this person out of here?"

"Wait a minute, bud." Wilding grabbed his arm. "Are you a doctor? They've got three in there already."

"So now they've got one more. Get out of my way." He tugged his sleeve from her grip and stepped toward the patient. She was alive, but just barely. Dr. Fulton, the neurosurgeon on call, rolled her over and attempted a hasty epidural blood patch on her spine as the nurse attached the IV to rehydrate her. This one had a tiny spinal puncture like nine of the others. The emergency treatment was going to be too late. She was dying. Grant checked her nose for encrustations and finding none, determined that fluid was not coming from a tear in the subdural meninges. CSF leaks without known origins, like head trauma or spinal taps, often started in the lower brain and drained into the nasal sinuses. The girl seemed well-nourished and in good health otherwise. Why wouldn't she have seen a doctor as the headaches increased as the fluid decreased? Why didn't any of them?

Grant reviewed the chart, staying until the young woman, SIH Case #15, was declared dead and the attending physician understood that the corpse was to be removed to the neurobiology research unit for autopsy before being released to family. He called down to his office and instructed one of the interns to grab the parents for a standard interview to make sure they had a full history. As the life support monitor was shut down and the team wandered away for the attendants to come in and clean up, he stepped through the curtain only to be face-to-face with Detective Wilding.

"Fellows. You're the one I should be talking to," she said.

"Maybe, but why should I talk to you? This isn't a police matter." He continued walking to his office. Wilding followed, almost skipping to keep up with his long stride.

"You're the dry brain guy, right?"

He smiled. "That's one way of putting it."

"So you could be a suspect."

He stopped. "What?"

"I thought that might get your attention, Sparky." She took a small notebook and pen from her pocket. "Tell me, doctor, what kind of medical expertise would it take to withdraw a lethal amount of spinal fluid?"

Grant couldn't help laughing. "You've got to be kidding. You think there's a mad spinal tapper out there?"

"A serial killer. I don't see what's so funny."

He rubbed his chin as he searched for words she would understand. "This is a medical mystery not a criminal mystery. Yes, we're seeing more cerebrospinal leaks than usual and the mortality rate is higher than expected but this is a known medical condition. That's why I'm doing my research. To find out why. What gave you the idea that there was something intentional happening here?"

"Some researcher you are. Haven't you seen the pattern? He's working his way up Water Street."

Each case from the first to the girl on her way to his autopsy room appeared on a city map in his mind. A cluster where Water Street dead ended at the treatment plant, then block by block into downtown. "Holy shit," he whispered.

The detective pushed aside Grant's folders and spread a map on his desk. She pointed to the icon for the water treatment plant. "After the seventh death down there, we were called in to move the winos out. I didn't think much about it until last June when the city attorney's nephew died from a spinal leak and an under-the-table investigation was requested. I was told it was an untreated spinal leak and it just happens sometimes. The CA wasn't happy to hear it but what could he do? Then I remembered that they said the bums all died from dry brains. I looked for a connection." Wilding took her pen and connected the dots on her map. "Angela Timsbury lived right here on Water Street East."

"Who?" Grant asked.

"The girl who just died. She had a name, you know. And parents and a little brother. She was nineteen years old. She studied sociology at the community college. Her boyfriend's name is Gerald and she liked to play basketball."

Grant refused to feel guilty about his ignorance of personal information. The survivor interview would pick up some of it and who cares what her boyfriend's name was? "The transients were malnourished and dehydrated and at high risk for SIH. We've been collecting data on the more recent cases. Case 15, Angela, is the second healthy one to expire from low CSF. Usually the symptoms of orthostatic headache, uh, headache when standing up, and violent nausea are so severe that treatment is sought early. The body only has about 150 milliliters—less than a cup—of CSF at any one time and replaces it two or three times a day. It's not easy to get what you call dry brain."

"Unless somebody's sucking it out."

"Like a vampire?"

"More like a murderer with medical know-how."

Before Grant could tell her she was jumping to an absurd conclusion, his phone rang. "Neuro. Grant speaking."

The voice on the line was timid. "Dr. Fellows, could you come down here? I was prepping 15 and. . . Could you come down and look?"

He could hear the intern breathing. "Well, what is it?"

"I'd rather you look. I'm looking at it but I'd feel more comfortable if you saw it, too."

Grant sighed. "I'll be there in a few minutes. Don't touch anything."

"What is it?" Wilding asked.

"A nervous intern, the bane of the university research scientist."

The student in his white lab coat stood at the door as Grant entered, Detective Wilding behind him. The nude body of Angela Timsbury lay on the stainless steel table.

"What's your name?" Grant asked

"James." The student swallowed. "Ellicott. James Ellicott, that is. Doctor." He tugged at his tie.

Grant shook his head. "All right, Ellicott, what's so amazing that I have to see it right now?"

Ellicott hurried over to the body. "I don't know if it's amazing. I just thought it was kind of, you know, funny. Well, not really funny. Peculiar. Yes, peculiar."

"Shut up, Ellicott." Grant looked at the girl's face. A pretty face without the dried vomit on the chin. "So?"

"Here, doctor." Ellicott turned the body on its side. "These bruises on either side of the spinal puncture. What does that look like to you?"

Grant noticed that Wilding had sidled up beside him. He bent down for a closer look at the gray marks on the skin straddling the backbone. Bruises often come to the surface after the blood settles to the lowest point and lividity sets in. They were irregularly shaped.

Wilding gasped. "Little hands!"

Ellicott smiled with relief. "That's what I thought!"

The bruises did look like two-inch hands had dug their fingers deep into the skin around the tiny wound. Grant's scientific mind immediately filed the observation under preposterous. Wilding and Ellicott looked at him expectantly. He cleared his throat. "It could be anything."

"Like what?" Wilding asked.

Grant scowled. "I don't know. She fell on something. Probably the same thing that punctured her spine."

"Doctor, wouldn't that kind of injury also cause bleeding?" Ellicott asked quietly.

Wilding headed for the door.

Grant followed her. "Where are you going?"

"I have an investigation to work on."

"Wait a minute." Grant walked with her to the exit. "What are you going to investigate? Baby vampires with spinal tap needles?"

"If that's what it takes," she called as she continued to the parking lot. "You coming?"

He shook his head. Somebody with sense had to be part of this. "Slow down, dammit!"

Wilding laughed.

Angela Timsbury's mother and father clutched each other's hands as they sat on their living room sofa, staring at the police detective and doctor. Grant felt as if they didn't understand a word Wilding was saying.

"I'd like to know what Angela was doing before she became sick," Wilding told them.

They didn't move.

"I'm trying to find out what happened."

Mrs. Timsbury blinked. A tear ran down her cheek.

Grant pulled his chair up to the sofa and took Mrs. Timsbury's hand. "Was Angela home when she got sick?"

She nodded and pointed up.

"May we have a look?"

She nodded again. Mr. Timsbury sobbed.

"Thank you." Grant motioned Wilding to follow him upstairs. The first door they came to looked like a teenage girl's room. The bed was unmade and clothes were tossed everywhere.

Wilding picked up a bra from the lampshade. "It could be a crime scene."

"The only crime here is slovenliness." Grant looked around. "You're the cop. What are we looking for?"

She shrugged. "Little footprints maybe."

They split up, looking at the mattress covered with clumps of dried puke, the shelves with romance novels and a stereo, the closet with more clothes on the floor than on the hangers. Wilding picked up a framed photograph of Angela with her arms wrapped around a lanky, grinning boy. "I got a question for you, doc. How do you explain the holes in the victims' backs?"

He grimaced at a pile of dirty underwear in the corner. "The holes, as you call them, are usually the size of a pin prick or not visible at all. It's been widely believed that bone spurs on the spinal column puncture the central canal but my research has shown microscopic evidence of an external epidermal opening. There's a reason why the intracranial hypotension is called spontaneous. No one has found a valid cause."

Wilding hunched down to study the carpet. "So people are springing leaks and the entire medical profession doesn't know why."

"You'd be surprised by how much we don't know." Grant wandered into the connecting bathroom. "Wilding, come here!" He walked to the open window and crouched to get a better look at the thick clear substance smeared on the wall beneath.

"Looks like snot." Wilding came up behind him, removing a small plastic bag from her pocket.

"It goes all the way outside."

"Or it came inside." Wilding scraped a small amount of the mucus into the baggie and sealed it shut. "Maybe the lab can tell us what this is. It'll take a few days at best."

Grant turned. "I've got a lab."

"It's all yours. Why don't you do whatever it is you do and I'll go down to the treatment plant."

"I'm going with you. We'll drop off the specimen with Ellicott. He can call when he's finished."

"Stop scaring him, then, or he'll never call."

The lights of the city were a half mile away. Wilding scanned the ground with her flashlight. Chain link fence topped with razor wire surrounded the plant. Beyond the parking lot, a culvert led to the storm drain that had been home to the men and women who died first from cerebrospinal fluid leaks.

Grant stopped as he realized where Wilding was going. "We're not going down there, are we?"

Without hesitating, she called back, "You don't have to."

He quickly caught up with her. "What do you expect to find?"

"The source of the snot." She climbed down the embankment and followed the culvert into the eight-foot-tall storm drain. Their footsteps echoed in the blackness. A faint smell of wood smoke and BO served as a reminder of the people who had lived and died here. The white cone of the flashlight moved methodically over the space, illuminating clothes and other belongings left behind. Grant felt very much out of his element. They moved slowly as the detective inspected side to side. Well into the tunnel, surrounded by the dark, the light no longer showed signs of past residents. Grant heard something hit the metal behind him. He swirled around and strained his eyes to see. Wilding brought the flashlight up and shined it toward the entrance. A figure shifted to the side.

"Who's there?" Grant's shout was answered with silence.

Wilding pushed past him, holding the flashlight in one hand and a gun in the other. "What did you expect? 'It's only me, the killer.'"

He felt ashamed of how frightened he was as he stayed close behind the tiny woman with the big weapon. As they approached the relative light of the opening, she whispered, "Stay here." He did as she said, even though he really didn't want to be left behind in the dark. He watched as her small shape moved away.

"Police!" she called. "Step out where I can see you!"

A moment later the figure was framed by the night sky beyond. "Who's that behind you?" a man's voice shouted.

"None of your business! Who are you?"

"You're a cop? You're kind of puny for a cop."

She tucked the flashlight under her arm and held up her badge. "I'm Detective Amy Wilding, city police. Now who are you and why are you here?"

He put his hands up. "I live up the road. My name's Jackson. The cops run all these fellas off a few months ago and I've kinda been keepin' an eye on the place. I saw you and whoever that is hidin' back there come in. That's all."

"Come on out, doc!" She pushed Jackson away from the storm drain and patted him down. Grant caught up with them as they climbed out of the culvert and into the parking lot.

Wilding took out her notebook. After taking down the man's full name and address, she asked, "What do you know about the deaths down here?"

"Who? Me?" He pulled off his baseball cap and ran his hand through his thin hair. "I don't know nothin' about that. Poor folks, all dying like that. It's a shame. I used to come down and talk to 'em about the old days before they built the treatment plant." He laughed sadly. "They used to call me crazy but a couple of them seen for themselves when they went down the culvert to take a dump."

"What did they see, Jackson?" Wilding asked.

Grant's cell phone played Beethoven's Fifth.

"The sprites!" Jackson replied cheerfully. "Water sprites!"

"Dr. Fellows," Grant said into the phone. Ellicott gave him the composition of the mucous sample. "Good work, James." He closed the cell. "Detective, I need to talk to you."

"Just a minute, Doctor. Do you drink, Mr. Jackson?"

"Nothin' but good ol' well water. I won't have nothin' to do with that crap from the treatment plant. Used to be sprites all over in the old days. Everybody saw 'em out by their wells. Then they brought in the city water and the sprites mostly disappeared."

Grant held up his phone. "I have the results."

"Mostly disappeared?" Wilding asked.

Jackson giggled and rubbed hands together. "Down in the woods, right down here." He pointed. "There's an abandoned open well, used to be for watering the cattle in the field."

"Will you shut up?" Grant shouted.

Jackson's face fell serious. He bunched his fists. "Who you telling to shut up, fancypants?"

Wilding stepped forward as Grant retreated. "Doctor, just because I have two ears doesn't mean I can listen to two people at once," she said. "Mr. Jackson, if I go to this well, will I see the sprites?"

He stuck out his tongue at Grant. "I'll tell ya, little miss. You might see 'em; you might not. They're a little bit invisible."

Wilding muttered an expletive. "Invisible. Great. Doctor Fellows, what did your boy have to say?"

Before he could speak, Jackson said, "Wait a minute. You come with me. I'll show you. Can't guarantee nothin' but if they're there and you look real careful, you just might catch a glimpse."

"Okay, Mr. Jackson. It's the doctor's turn."

"Ellicott tested the sample," Grant said, shooting the most evil look he could muster at Jackson. "It was composed primarily of water, glucose, and proteins."

"And that means what?" Wilding asked.

"It was similar in composition to human mucous secretions."

"You mean it was snot."

"Yes and no." He realized he was sounding like Jackson. He quickly continued. "It wasn't snot. It had more solids, so it was much thicker. More like cartilage. And it had a high mineral content unlike snot. More like cerebrospinal fluid. It was especially high in magnesium."

Wilding held out her hands. "What the hell are you saying?"

Grant rubbed his chin. "I don't know. I don't know what it is. Maybe Ellicott screwed up."

"So where does this leave us?"

He didn't have an answer. He suddenly felt very foolish standing in the woods at night with the police detective and Andy of Mayberry. He didn't belong here. He should be back in his lab, using science to find answers. Not crawling around sewers and listening to some rube blathering about fairies in his well.

Wilding pocketed her notebook. "You finished for the night, Doctor? I can drop you at your car at the hospital."

"Yeah, I think so. Where are you going?"

"I'm going to follow the dots up Water Street and stop by each vic's home."

Jackson stepped forward, waving his arms. "Y'all can't go yet! You gotta come see the sprites! It's the perfect time. They don't come out in the daylight. It's not far. The well's just down here a piece."

A connection clicked in Grant's head. Untreated well water is often high in magnesium. The pseudo-snot and CSF are high in magnesium. His data hadn't shown significant mineral deficiencies across the board, only in the homeless, but none of the cases had the recommended levels of magnesium. Maybe the water treatment was a factor. Until a few years ago, the area was rural and even city hall had well water. He couldn't recall any research tying compromised neural systems to any specific nutritional element but it was something to look into. He clapped Jackson on the back. "Let's go take a look at your gremlins, Mr. Jackson."

"They're sprites," he said.

Wilding stared at him, her mouth dropping open.

"Coming, detective?" He enjoyed her reaction.

She leaned in close to him as they followed Jackson back into the culvert and into the scruffy stand of trees and undergrowth. "What are you doing?"

He smiled. "I'm getting a water sample from the well."

"That's important?"

"I don't know. I'm just following a lead." He stumbled over a root.

"Here it is, kids!" Jackson announced joyfully. "Find yourself a stump, have a seat and watch."

Grant stepped through the weeds toward the concrete structure. Wilding had given him one of her zipper bags.

"Whoa, hoss!" Jackson grabbed his shoulders. "You don't want to go near there."

"Why not?"

"City people," Jackson said. "Didn't your mama teach you nothin'? You don't mess with the sprites. They bite."

Grant walked back to Wilding. "You don't suppose there's a wild animal back here, do you?"

"Who knows?" she whispered. "The guy's obviously some kind of a nut." Aloud, she said, "Mr. Jackson, we've got it covered here. Why don't you go home?"

"No, that's okay, little miss. I'd like to see a sprite. I ain't seen one in years. Just sit and wait. Keep your flashlight down and when you hear something in the brush, shine that light right at it." He flumped down onto a log.

Wilding sat beside Jackson. Grant leaned against a tree, fuming because he wanted to get the water sample and get the hell out. What felt like hours, but was actually minutes, passed. The stars peeked through the treetops. Crickets chirped. The loam beneath the underbrush smelled of mildew.

Something moved by the well.

Before he could speak, Wilding shushed him. She shined the light onto the base. Grant wanted to say that it was probably a rat but he knew she would shush him again. He waited as she turned off the flashlight, leaving them in total darkness. A moment later, at the hint of a rustle in the dry leaves, she flicked it on.

The light reflected on the shiny surface of a foot-high creature, standing upright, looking straight at them. In the second before it darted away, Grant saw a face that was almost human.

Jackson danced around them. "Did ya see it? Did ya see it? Hoo-ee!"

"What the hell was that?" Wilding shouted.

Grant found himself speechless. He saw the creature in his mind as he tried to rationalize it. All of this talk of imps and such influenced his perception. The light shined on a skunk or a woodchuck, that's all.

"What the hell was that?" Wilding shouted again.

"Sprite! Sprite!" Jackson sang as he danced.

Grant felt as if he were a bit actor in a bizarre play. He had to do something normal. Something scientific. He took out the baggie and walked toward the well.

"Be careful, boy," Jackson said menacingly. "If'n the sprite don't get ya, you might just fall into that old well."

"I'm taking a water sample."

"Hope you have long arms. That well hasn't been used in years. The only water might be thirty or so feet down."

Grant wanted to go home. He wanted to go home now.

Wilding appeared to have composed herself enough to approach him and take his arm. "Let's get out of here, doc." As they walked away, she called over her shoulder, "Jackson, I'd go home and lock the door if I were you." She didn't speak again until they were inside the car in the plant parking lot. She started the engine. "You saw what I saw. I know. That wasn't human. And it wasn't an animal."

Grant cleared his throat. "It was a second. A split second. We couldn't tell what it was. We need more data."

"Doctor, use your gut, your instinct. That could be our spinal fluid sucker. The size fits with the hand bruises and the damn thing looked like it was made of Jello."

"Earlier today you thought it was a serial killer in a medical profession. By the way, don't detectives travel in pairs like nuns? Don't you have a partner?"

She put the car in drive and pulled onto Water Street. "I'm working this unofficially."

Grant laughed. "Your superiors thought you were crazy, right?"

She took her hand off the steering wheel long enough to show him her middle finger.

As they drove into town in silence, Grant tried to organize in his mind what he had learned this day. Babies can spontaneously recover from hydrocephalus. Healthy young women with little brothers and boyfriends named Gerald can die suddenly from a condition that's usually not fatal. A strange gooey substance high in magnesium could be residue from a CSF-sucking sprite.

Even though he was trying to be facetious, he couldn't help but think it made sense. If the creature required high levels of magnesium and could no longer get it from the well water, it would look for another source. The river feeding the treatment plant would be too fast moving for a small creature. The homeless in the storm drain filled that need until they were moved out. Then it headed up the street and found healthy people with higher levels of magnesium. And little brothers.

Wilding pulled into the hospital parking lot.

"Stop the car!" Grant yelled. "Turn around!"

She slammed on the brakes, throwing them both forward into their shoulder harnesses. "What?"

"The Timsburys. They have another child. The brother. What if it's still in the house?"

Wilding spun the car around and stepped on the gas.

Mr. Timsbury's grief had subsided enough for him to be outraged. "Leave us alone! Our daughter is dead. We just want to be left alone!"

"We only need a minute, Mr. Timsbury, please." Wilding inched into the doorway. "Is your son home?"

"He's gone to bed. He doesn't want to see anyone."

Grant stepped forward. "I'm a doctor, Mr. Timsbury. A neurologist. I was in the emergency room when they brought your daughter in. Angela. I'd like to give your son a brief examination. What's his name?"

"Matthew. Matt. Is what Angie had contagious?"

"No, but I need to see Matt now. You can take me up to his room."

Mr. Timsbury opened the door and led them up the stairs. He tapped on the door opposite his daughter's. "Matt? Open the door, son."

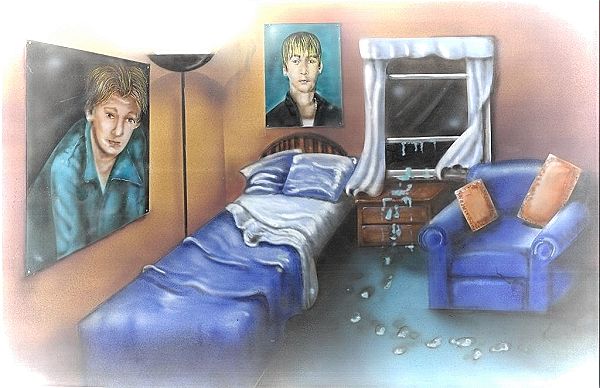

When there was no response, Wilding reached in front of him and threw the door open. The light was off and Grant could see a shape on the bed. "Matt!" he shouted as he flipped on the light switch.

A boy lay motionless face down on the bedclothes, his pajama top pulled over his head. Crouched on his back, a clear gelatinous creature turned to face them. Its eyes were slits; it had no nose. A needle resembling an icicle protruded from an O-shaped mouth. A high-pitched wail emitted from the creature as it slid off the child and under the bed.

Wilding pulled her gun. Grant grabbed her wrist. "No. That won't work. Mr. Timsbury! Get Matt out of here. Call 911." He closed the door behind the father carrying his son.

Wilding pulled the covers off the mattress and knelt on the floor to see the cowering sprite. "What should we do with it?"

Grant thought about the composition of the sample sent to the lab. "Don't let it get away. I'll be right back." He stopped at the door. "And don't let it get near you!"

He heard the ambulance siren as he ran down the stairs and into the kitchen. He flung the cabinets open, tossing anything in his way onto the floor. He found what he was looking for and ran back to Matt's room.

As he slipped in the doorway and pushed the door closed with his shoulder, he saw Wilding sitting on the floor, both hands gripping a translucent leg.

"I got it! I got it!" she shouted. "Look! It's missing a chunk. Angela must have put up a fight!" As she smiled at him, the creature twisted around, jumping on her chest, and injected the needle into her neck.

"Amy!" Grant strode forward and tore open the pound bag of salt and dumped it over the sprite's body. It dropped away from the detective and howled as it melted into a foul-smelling puddle. The needle was the last feature to liquefy.

Grant knelt next to Wilding and examined her wound.

She coughed when she tried to talk. Clutching her throat, she managed to ask, "How did you know to do that?"

He wrapped his arms around her. "It works on slugs."

The new lab equipment took up so much of the space that Grant kept one of the covered aquariums in his office. He had gotten into the habit of reaching over and tapping on the glass without looking up from his work whenever it got noisy. It had taken him a week to realize that little Cody Allen lived on Water Street. He had to go back to the well in the woods at night to capture one of the sprites. Amy insisted on going with him. He knew he wouldn't get any federal funding with just a proposal. He had to show them that these creatures really do exist.

Marianne leaned into the doorway. "Doctor Fellows, are you here for Detective Wilding?"

"Very funny," he said. The staff was having way too much fun with his newly found love life. He could see Amy standing behind her. Marianne covered a laugh as Amy entered the room.

"Okay, doc, it's quitting time." She walked over to the aquarium. "What's this?"

"It's my new little buddy."

The sprite shuddered as it fed on the rhesus monkey with an enlarged head, face down on the aquarium floor, eyes wide with terror.

Grant recorded the time as the creature withdrew its transparent needle from the limp victim. As the sprite hopped off the monkey's back, it belched, sending little bubbles through its body. It almost disappeared as it hid in the glass corner.

"He's curing monkey hydrocephalus now," Grant said, "but the little snot'll be curing babies and car accident victims in a couple of years."

Amy grimaced, then leaned in for a closer look. "Does he have a number or a name?"

Grant smiled. "He has a name all right. I call him Jackson. Hoo-ee!"

Barbara Ferrenz is the author of "Worse Than Death."