"It's very much as I expected," the intruder said without preamble.

Entering my cozy den, I had encountered him seated in my massive leather wingchair, shoes up on my broad mahogany desk, savoring one of my Cuban cigars. A snifter of brandy rested on the leather blotter, within his easy reach. The aroma was Napoleonic.

As I was unsurprised to find him. "Please, don't get up."

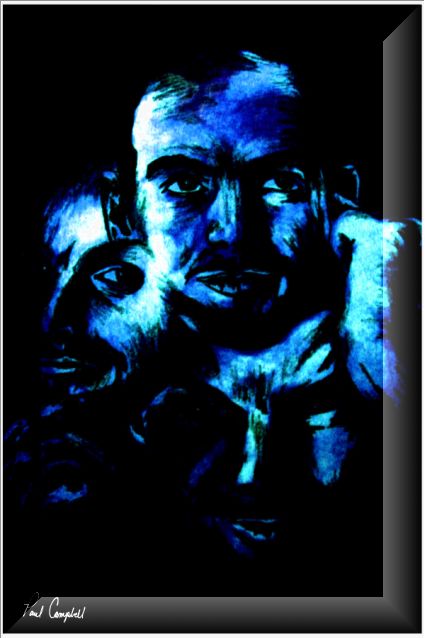

"You're very gracious." He grinned. The smile was world-famous: toothy, and slightly off-kilter. I saw it every morning in the mirror. Not that there weren't differences. There always were: in haircut, clothing style, glasses instead of contacts, whatever. I found his sideburns curiously short. "I mean considering."

Considering, as we both knew, he was here to take my life. Leather squeaked as his feet swung from the desk and he straightened his posture. Getting down to business. "The greatest minds of the millennium could not reach a common understanding what the math meant." Meaning: He couldn't have been expected to figure it out.

He was a whiner, a self-justifier—for which I was grateful. That character flaw was the only reason I was still here. He was also wrong. Proof by counterexample: I had decided I would solve the puzzle. Eventually, he had made the same choice. And, in our own times, in our respective ways, each of us had been successful.

His over-rehearsed rationalization tumbled out. "Bohr, Heisenberg, Einstein, Pauli, von Neumann, Schrödinger, Planck . . . them and more. Giants. You know the list. They never agreed on the physical significance of the math. Who was I to hope to understand the reality underlying the mathematical formalism of quantum mechanics?"

Meaning: He lost hope, and somehow it became justifiable that I should pay the piper.

"And so for a long time, I gave up. I denied the problem. My career went another way." He paused for a sip. "But for years, for decades, I could not help but wonder. Every day, billions of transistors demonstrated some underlying truth to the theory. Quantum mechanics describes something. I had to know what."

His non-smoking hand, when not busy with the consumption of my best brandy, darted from time to time to pat something unseen in his coat pocket. It seemed to give him confidence.

"And so you returned to physics." I had never left it.

He admired the many plaques and photos gracing the darkly paneled walls of the room. "And so I realized, I decided, what you had much earlier. The Copenhagen Interpretation—that certain physical specifics go beyond being unmeasurable, that to even inquire about them represented a misunderstanding of the physical universe—was, if true, an explanation inherently unprovable.

"What was provable, if true, was another explanation altogether: the Many Worlds Interpretation. If I could detect other universes, show that events happened in all possible ways, not just in whatever random way 'the wave function collapsed' without cause or explanation in ours, the great QM debate would be resolved. But among the myriads of myriads, for which other universe would I aim? And what evidence of that other place would be unambiguous?"

His nervous pocket-patting was growing more frequent. If my suspicions about the device in that pocket were correct—and who better than I to understand my visitor's thinking—I did not have much time. "And then you realized . . . if MWI were true, there must be other universes in which another you"—such as me—"had stayed the course." My eyes followed his to the Nobel Prize certificate and medallion in their softly illuminated, velvet-lined display case.

Because you got greedy. You saw you need not settle for fame beginning at age fifty-five—my present age, hence your own. You could do better. Much better. By switching places, you could seize the fruits of fame from another you who had proven the MWI years earlier.

Do you think you are the first me to have had that realization?

Below his line of sight, I clicked my heels twice. The radio beacon thus triggered activated the mechanism hidden within my/his chair.

There are universes without number. Among the myriads is one where a different quantum outcome was enough to change the career of an unknown microbe. Newton died there in the great plague of 1665, at age twenty-three. The development of physics was, as a result, greatly impeded. Onto that parallel, low-tech plane of existence now materialized a new occupant.

I am not a cruel man. I sincerely hope my recent visitor—and the dozen earlier versions of me—enjoy their opportunity to make real advances in physics.

Edward M. Lerner is a physicist, computer scientist, and curmudgeon by training. Now writing full-time, he applies all three skill sets to his science fiction. His web site is www.sfwa.org/members/lerner/